Amy Sherald at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis

(Left) Amy Sherald, A clear unspoken granted magic, 2017 © Amy Sherald. Collection of Denise and Gary Gardner, Chicago. (Right) Amy Sherald, What’s precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its presence (All American), 2017 © Amy Sherald. Private collection, Chicago. Courtesy the artist, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago and Hauser & Wirth.

Amy Sherald at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis

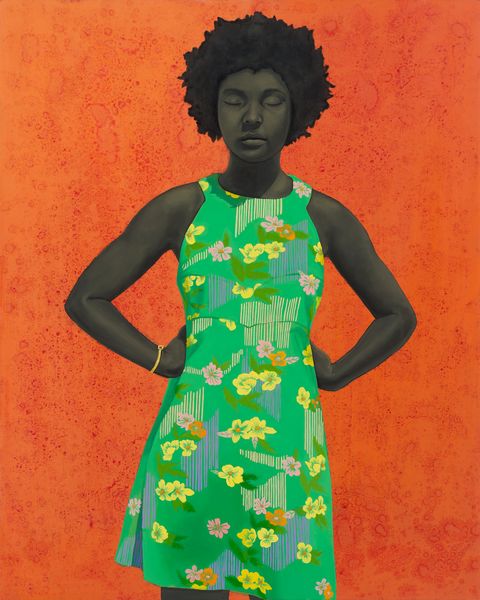

Amy Sherald paints portraits of everyday African Americans she encounters on the street, in the grocery store, on the bus. Yet her subjects embody the ineffable quality of ‘existing in a place of the past, the present, and the future.’

‘When I choose my models,’ the artist has said, ‘it’s something that only I can see in that person, in their face and their eyes, that’s so captivating about them.’ Through her vibrant, sometimes fantastical portraits, Sherald captures the essence of her particular subjects while engaging in broader dialogues about the black experience, the performance of race, and the historic lack of non-white representation in the Western art canon.

Through a number of intuitive formal choices, Sherald constructs liminal worlds - both real and constructed – in which her characters exist. Set against a color-field background and divorced of context, time, and place, the life-sized, frontal figures are dressed in costumes and carry objects that indicate their daily activities or imagined or perceived selves.

Although each subject – painted with sober realism - bears clear resemblance to the sitter, Sherald adds the props and clothing, conjuring the figure’s possible alternate self, and perhaps hinting at the complexity and performance of identity and race. The figures gaze out at viewers as if to assert their presence in a genre of painting from which African Americans have been largely excluded.

The skin is rendered in grayscale, which refers to not only black-and-white photography – Sherald paints from photographs – but also the artist’s intention to ‘remove color from race,’ shifting the conversation toward the humanity and individuality of each figure. The titles of the paintings can be both descriptive and whimsical, giving viewers pause and inviting us to revisit the subject in our imagination.

Amy Sherald, Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, 2018 © Amy Sherald. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Courtesy the artist, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago and Hauser & Wirth.

Amy Sherald, The Bathers, 2015 © Amy Sherald. Collection of Pamela K. and William A. Royall, Jr., Richmond, VA. Courtesy the artist, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago and Hauser & Wirth.

On Painting Michelle Obama In 2016 Amy Sherald won the National Portrait Gallery’s prestigious Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, from a pool of more than 2,500 artists. As the first woman and the first African American artist to win the prize, Sherald gained widespread recognition.

The following year in October 2017 it was announced that Sherald was commissioned by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery for the official portrait of the former first lady, Michelle Obama – and Kehinde Wiley for the former President – the first African American artists to have been selected to paint a presidential couple for the Gallery.

The artist is known for making portraits of everyday people, and she has expressed how painting the former first lady was no different for her: ‘I feel like she really represents what I paint, which are American people. They are black people doing stuff… And black people become first ladies. For me, it feels natural to have her as a subject.’ Sherald notes the familiarity of Mrs. Obama: ‘She’s an archetype that a lot of women can relate to – no matter shape, size, race or color.

We see our best selves in her.’ In her speech at the portrait unveiling, Mrs. Obama commented on the lack of black women in portraiture and shared her hope that Sherald’s portrait would inspire younger generations. Mrs. Obama said, ‘I’m also thinking about all of the young people, particularly girls and girls of color, who in years ahead will come to this place and they will look up and they will see an image of someone who looks like them hanging on the wall of this great American institution.

And I know the kind of impact that will have on their lives because I was one of those girls.’ More than 176,000 people visited the National Portrait Gallery in February 2018, the month the painting was unveiled. The Process Sherald creates approximately 13 paintings per year. She admits that it is difficult for her to find people to paint. When she does find that person with a particular quality visible only to herself, Sherald notes: ‘It’s the same feeling that you get when you first saw your husband or wife.

I look at them and I am like ‘ta da’... I text them my website and I get their email address to make sure that I don’t lose them... Sometimes I’ll call them right back, two weeks later. Sometimes it could be a year.’ When she decides to move forward with a portrait, the artist then selects an outfit for the sitter or may ‘shop from their closet.’

Next she photographs her model in an outside setting because of how the natural light highlights the textures of the skin. Sherald makes intuitive decisions on how to represent the clothing and what props to add, referencing her archive of patterns and textures she culls from the internet.

Amy Sherald, Mother and Child, 2016 © Amy Sherald. Collection of Dr. Anita Blanchard and Martin Nesbitt, Chicago. Courtesy the artist, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago and Hauser & Wirth.

Portraiture and the Use of Grayscale Sherald engages with multiple artistic histories to explore race in portraiture. Sherald paints from her photographs of the model and places the figure in a color-field background, calling to mind 16th-century Northern Renaissance portraiture, in which figures are captured against similarly arresting monochrome colored backgrounds.

Sherald spent a year studying with the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum, who taught her the classical technique of beginning a portrait by modeling the figure in grisaille – or grayscale, which evokes black-and-white photography. Historically, black people have not had paintings to represent them, so photography’s advent was the first moment in which black sitters became the authors of their own narrative.

The photograph represented a certain truth to black experience – a truth still relevant to Sherald’s process, working from photograph to painting. Sherald has observed, ‘My work began as an exploration to exclude the idea of color as race from my paintings by removing ‘color,’ but still portraying racialized bodies as objects to be viewed through portraiture.’ So by painting the skin in shades of gray, the artist has sought to even the playing field, while simultaneously inserting these black figures into the largely white portraiture tradition.

Sherald also works against the historic exclusion of black representation in art museums – institutions that assign cultural value through decisions to exhibit or collect one piece of art over another. ‘I think black artists are inspecting our own humanity, altering perspectives, producing some of the best work out there now,’ the artist said recently, ‘and creating space for ourselves in these institutions.’

Amy Sherald, The Make Believer (Monet’s Garden), 2016 © Amy Sherald. Collection of Andreas Waldburg-Wolfegg, Chicago. Courtesy the artist, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago and Hauser & Wirth.

Amy Sherald (b. 1973, Columbus, Georgia) lives and works in Baltimore. In 2018, Sherald’s official portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama was unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Sherald received the Driskell Prize for African American Art from the High Museum in 2018. In 2016, Sherald was the first woman to win the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition grand prize; an accompanying exhibition, The Outwin 2016, has been on tour since 2016 and opened at the Kemper Museum, Kansas City, Missouri, in October 2017.

Sherald has had solo shows at venues including Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago (2016); Reginald F. Lewis Museum, Baltimore (2013); and University of North Carolina, Sonja Haynes Stone Center, Chapel Hill (2011). Group exhibitions include Fictions, Studio Museum in Harlem (2017–18), Southern Accent, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham (2016), which traveled to Speed Museum of Art, Louisville (2017); and Face to Face: Los Angeles Collects Portraiture, California African American Museum, Los Angeles (2017). Public collections include Embassy of the United States, Dakar, Senegal; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.; Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.; Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.; The Columbus Museum, Columbus, Georgia; Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri; and Nasher Museum of Art, Durham. Sherald was recently appointed to the Board of Trustees at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Sherald received her MFA in Painting from Maryland Institute College of Art (2004) and BA in Art from Clark Atlanta University (1997), and was a Spelman College International Artist-in-Residence in Portobelo, Panama (1997).

Related News

1 / 5