Over the past four decades, Sonia Boyce DBE RA has cultivated a multidisciplinary practice that explores play, language and pattern, while questioning the nature of representation and authorship. For her inaugural exhibition with Hauser & Wirth, Boyce will present two new films alongside her latest wallpaper and photographic works.

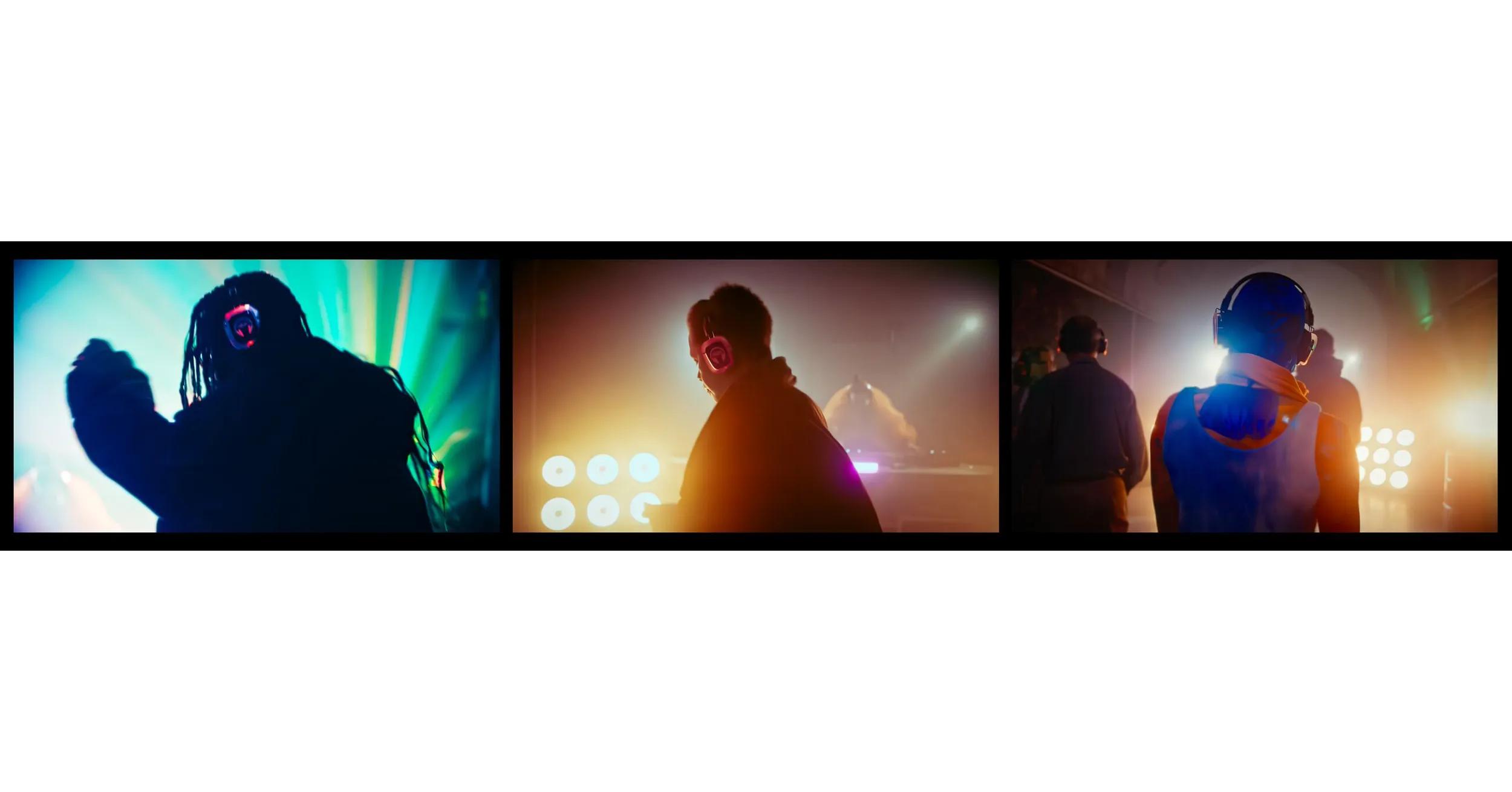

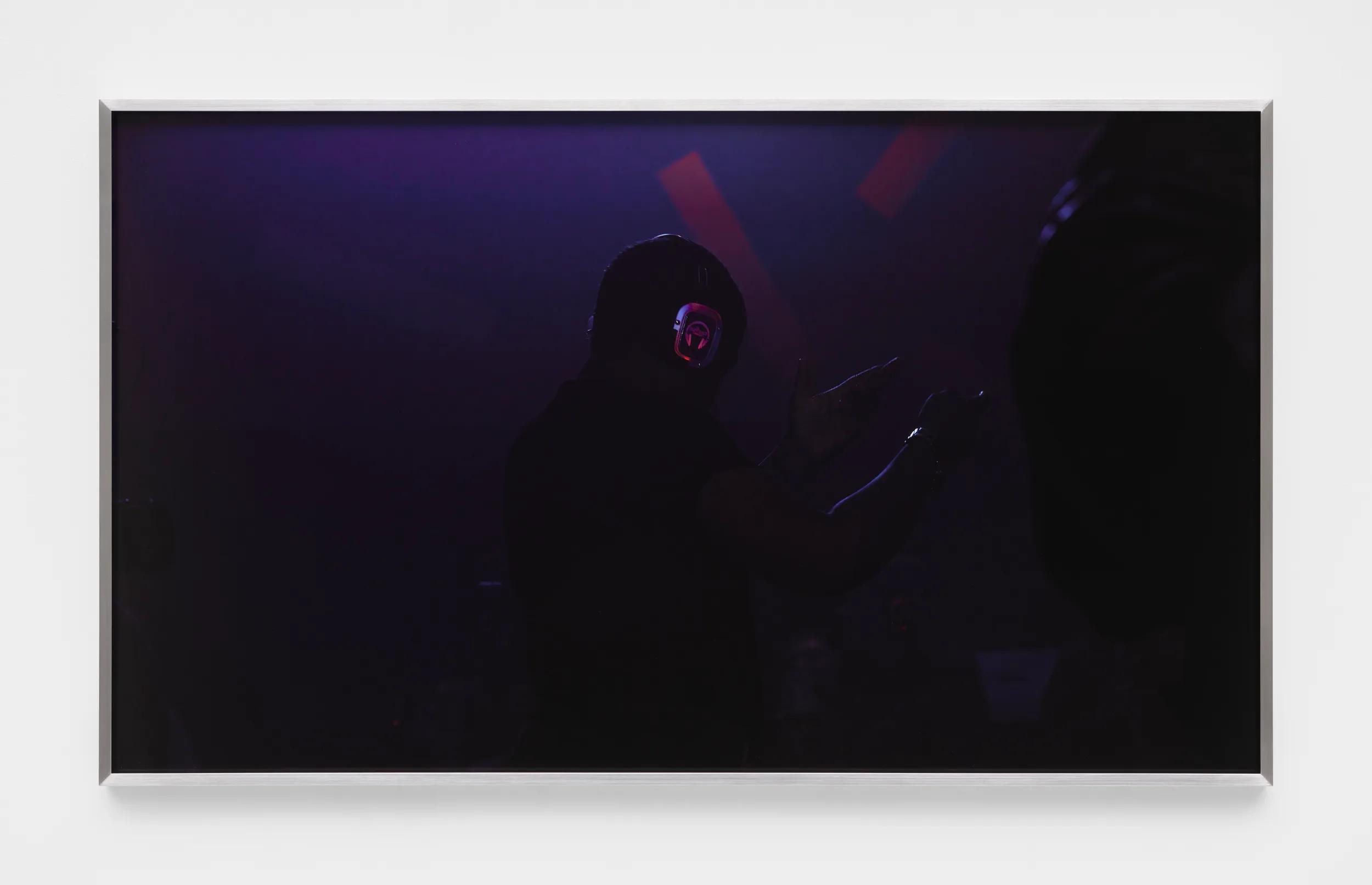

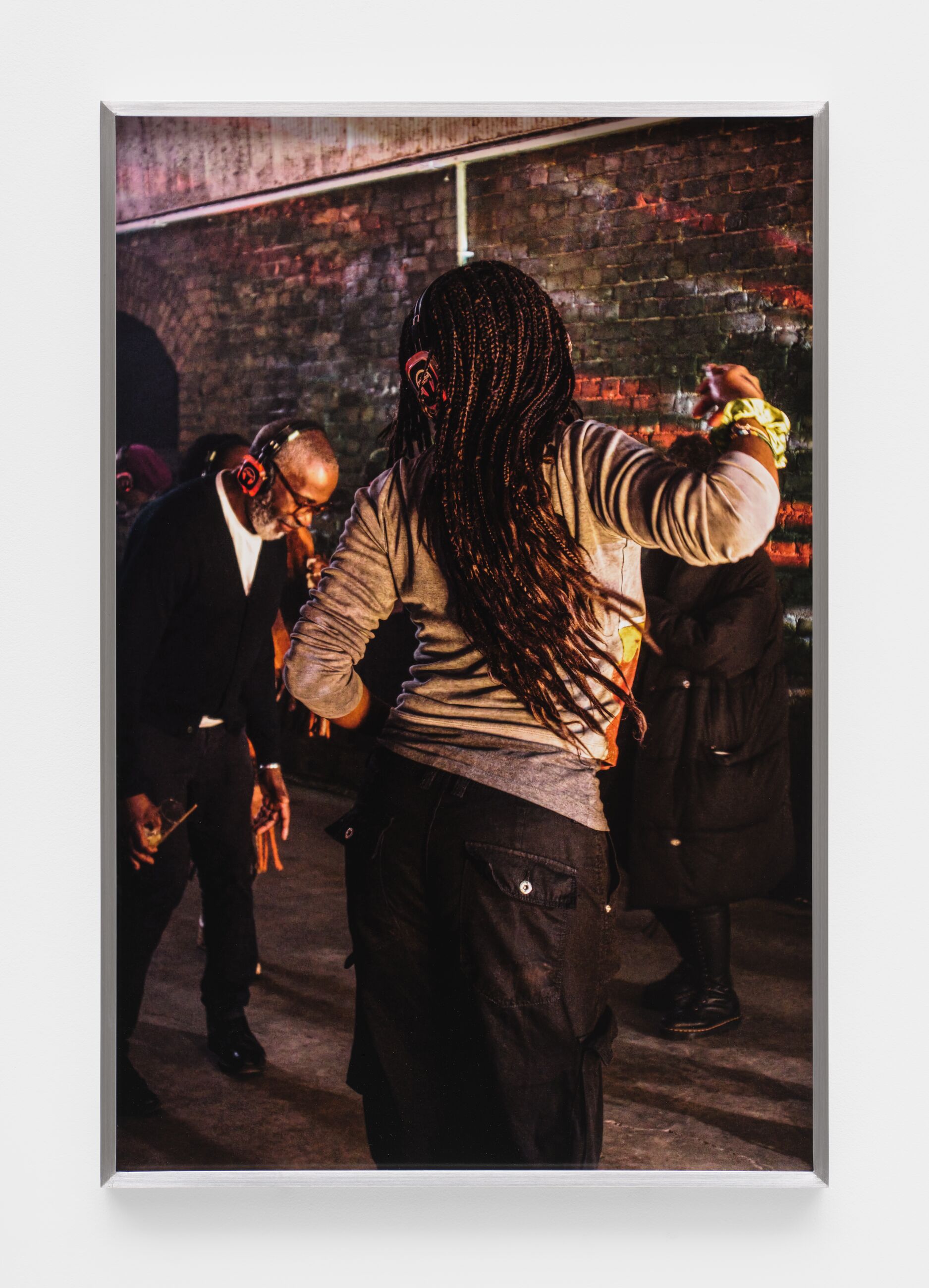

In the first film on view, Boyce weaves together footage captured at a silent disco, a paradoxically hushed event in which a roomful of dancers responds to music heard only through headphones. Inspired by both Roy DeCarava’s ‘Dancers, New York’ (1956) and Adrian Piper’s ‘Funk Lessons’ (1983)—groundbreaking works by artists who have centered Black culture—Boyce’s ‘Silent Disco’ (2025) revels in the dancers’ unguarded gestures, flickering emotions and ephemeral exchanges. Using montage and repetition, among other techniques, the film takes these lively impressions ‘for a walk,’ as Boyce would say, quoting Paul Klee’s adage (‘Drawing is like taking a line for a walk’). As the film begins, only ambient noises are audible to the viewer: we hear the soft shuffle of feet, train cars passing outside the venue, murmurs that erupt into sudden bursts of song. Gradually, the music builds, coaxing the dancers into collective movement, though their headsets are tuned to two separate channels. Harmony arises, improbably, from dissonance.

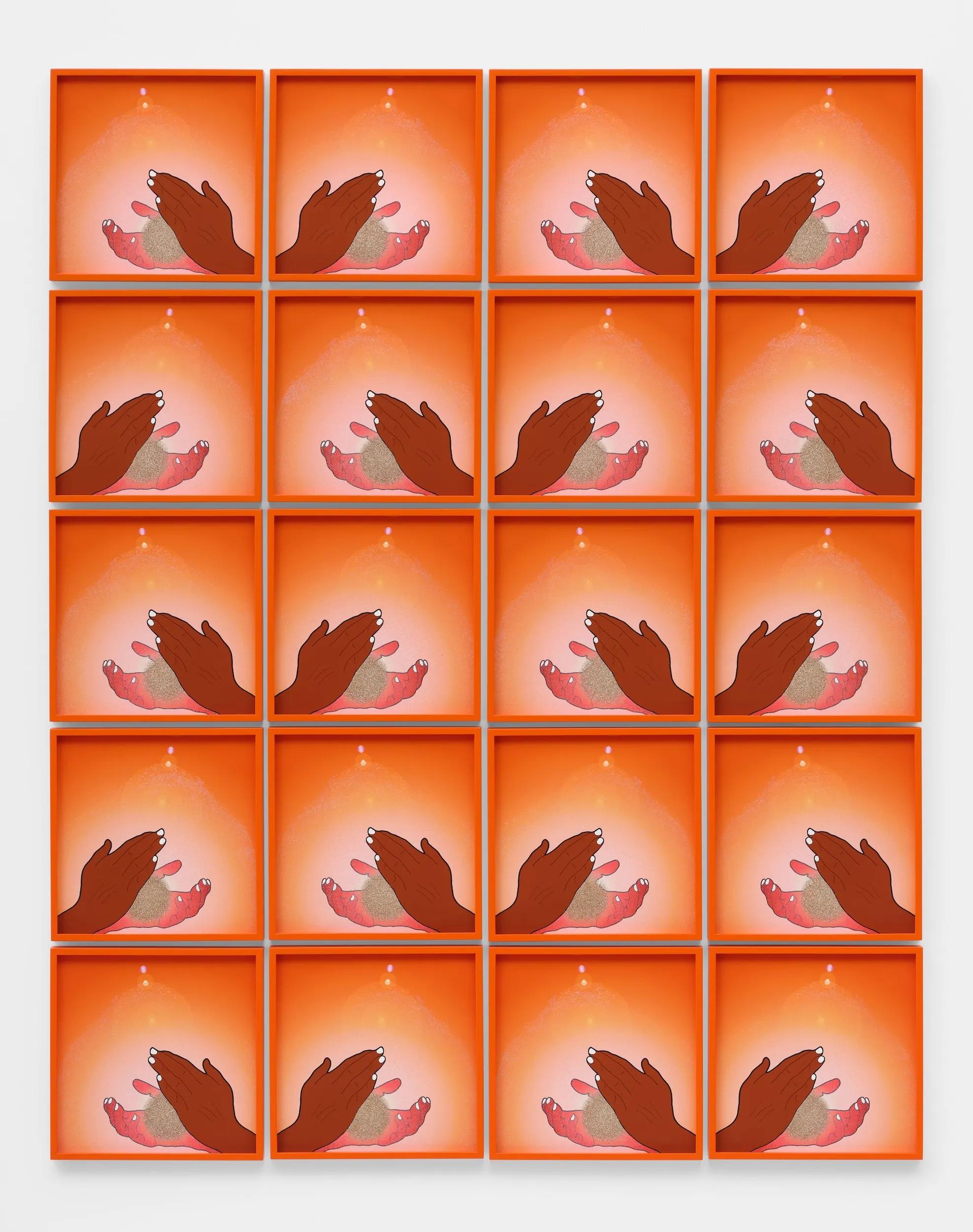

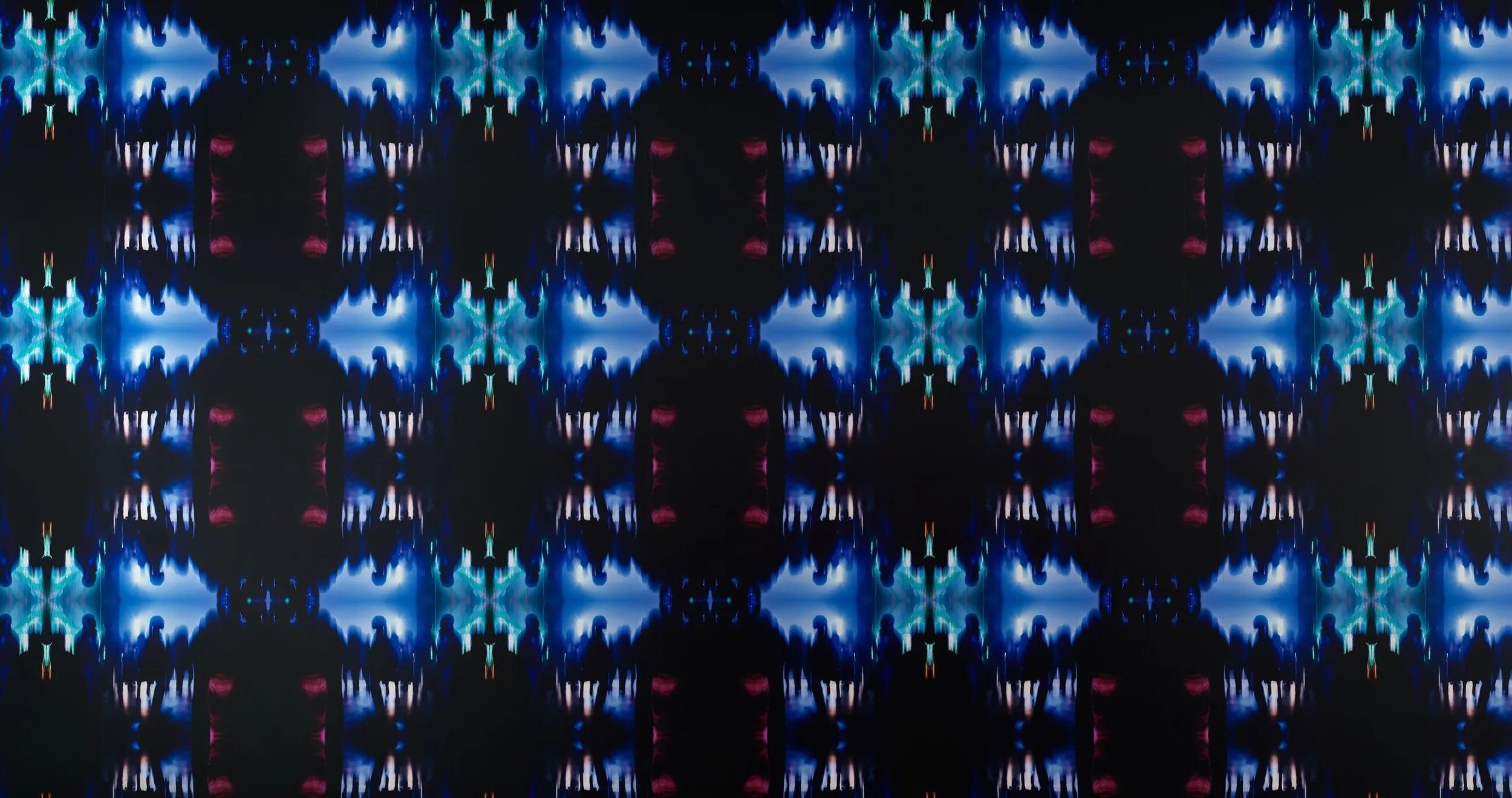

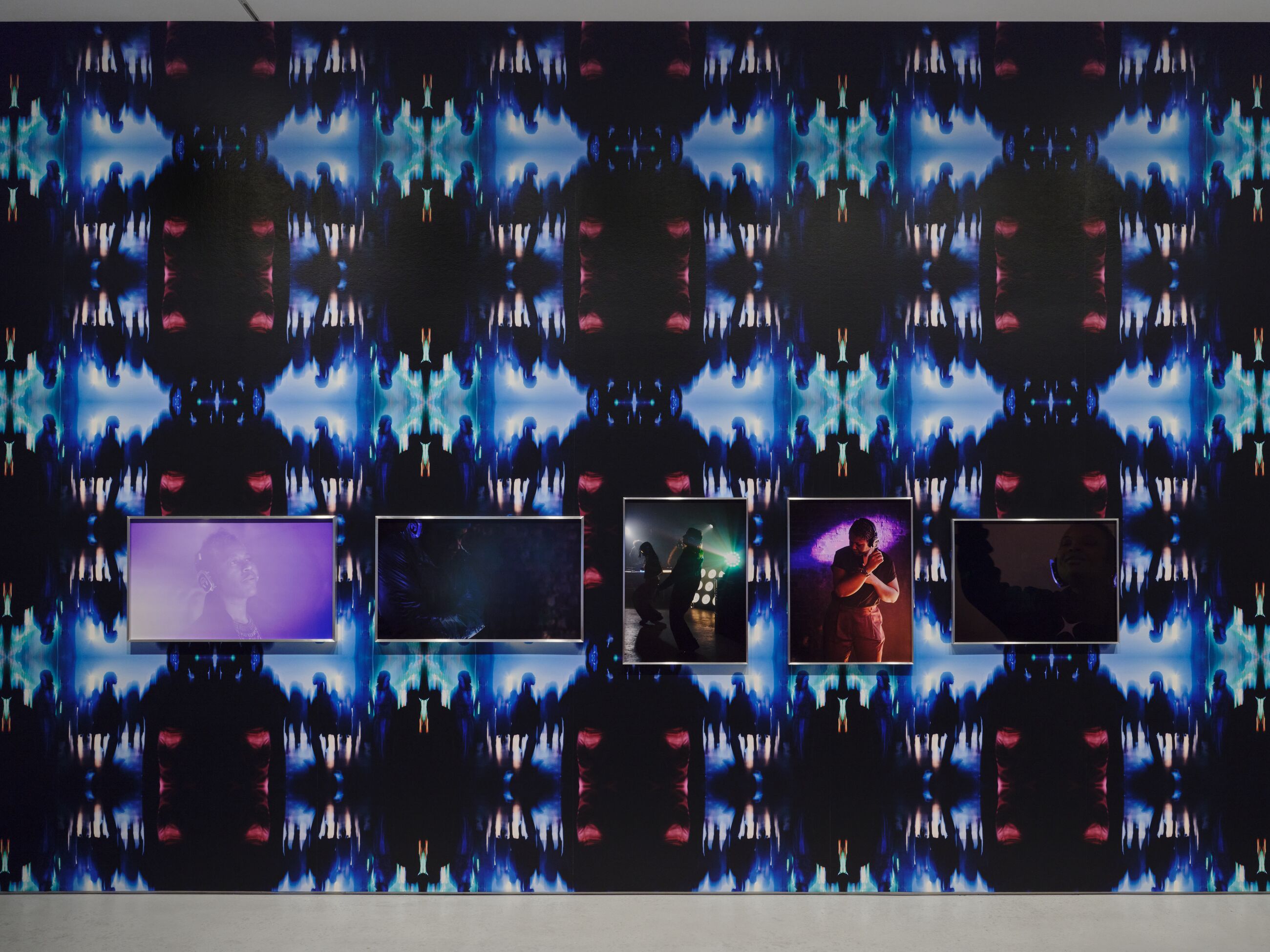

A key subject in Boyce’s recent work, the silent disco is not a party, but rather a framework for close listening, improvisation and collective performance. This sense of openness and play continues in the exhibition space itself. Boyce has taken still images from ‘Silent Disco’ and arranged them into repeating, kaleidoscopic patterns to create wallpaper installations within the gallery, blurring distinctions between the artwork and its means of production and display. Boyce’s installation immerses us in subtle cues from the original performance—the lights, the uncanny silence, the dancers’ whirling bodies—suggesting that at any moment, the disco could begin again.

Installation Views

1 / 5

Getting to Know: Sonia Boyce

Inside her exhibition at our New York gallery, Sonia Boyce DBE RA met with a group of young people from Culture for One to talk about her new body of work. The film is produced in partnership with Culture For One, a non-profit organization committed to improving the lives of New York City children and young adults living in foster care by providing them with arts opportunities and exposure to local cultural communities.

Sonia Boyce: Wallpaper

For the cover story of Ursula magazine’s summer issue, British artist Sonia Boyce sat down in her studio to talk about the social, political and ethereal roles of wallpaper—a touchstone in her work. Directed by Yvonne Zhang, this is the seventh installment in our Material series—which explores, in print and on film, artists’ transformation of raw materials into finished works.

Related Content

About the Artist

Sonia Boyce

Over the course of four decades, Sonia Boyce DBE RA has developed a powerfully original practice that transcends boundaries as an interdisciplinary artist and academic working across film, photography, print, sound and installation. Boyce creates immersive and experiential spaces that explore themes of play, disruption and revelation in which the audience become active participants. Boyce’s practice today is focused on questions of artistic authorship and cultural difference. She continues to break new ground through her commitment to questioning the production and reception of unexpected gestures, with an underlying interest in the intersection of personal and political subjectivities. In 2022, Boyce presented ‘FEELING HER WAY’, commissioned for the British Pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition—La Biennale di Venezia for which she was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation.

In 1980, Boyce completed a foundation course in art and design at East Ham College of Art and Technology, London, and in 1983, she received a BA in fine art from the former Stourbridge College in Stourbridge, England. During her time at Stourbridge College, Boyce attended the First National Black Art Convention at the nearby Wolverhampton Polytechnic. It was here that the artist would meet peers Lubaina Himid and Claudette Johnson, and become part of the British Black Arts Movement of the 1980s. Her large-scale pastel works from this brief period depicted domestic scenes from Afro-Caribbean life in the UK, drawing on Boyce’s personal experiences from her family and childhood. Foregrounding her own experience, works such as ‘Missionary Position II’ (1985) and ‘She Ain’t Holding Them Up, She’s Holding On (Some English Rose)’ (1986), explore questions of identity, race and cultural difference, themes, along with self-narration, that would continue to inform her career.

Boyce moved away from self-representation soon after and embraced an increasingly conceptual, social art practice. Utilising a range of media including photography, video and installation, her work developed into a collaborative mode of working, engaging with the audience in playful yet provocative situations. Despite this shift in method, issues of the body would remain central at this stage. In the early 90s, the artist began buying and collecting hair from Afro-Caribbean hair shops, which she turned into a series of 50 small, handheld sculptures from her Do You Want to Touch? series, objects that Boyce describes as ‘fragments of the African diasporic body’. Questions of the Black body as ‘other’ are also explored in the photographic installation work ‘The Audition’ (1997), in which Boyce invited members of the public to be photographed wearing a costume afro wig.

Since 1990, Boyce has been closely collaborating with other artists, frequently involving one- off improvisations and spontaneous performative actions made by the collaborators. Key works in subsequent decades include Boyce’s filmed improvisational performance ‘For you, only you’ (2007) that brought together a choir singing a piece of 15th-century sacred music and the artist Mikhail Karikis, who communicates with the choir in a series of non-verbal stutters and guttural vocalisations. In later works such as ‘We Move in Her Way’ (2017), the artist combines improvisational sound and movement performances from Elaine Mitchener and Barbara Gamper. Boyce documents these improvised encounters without intervening, and later constructs them into immersive multi-media installations.

For her latest installation work, ‘Feeling Her Way’ (2022), part of her presentation for the British Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, Boyce recorded five intergenerational Black female musicians interacting, improvising and playing with their voices, exploring the notion of what it means to be free. As Boyce says of her interest in exploring social dynamics, ‘I’m more interested in human responses than anything else…how to learn, how to listen, how to watch things and be in it; not be separate from it, not to have a kind of arm’s length relation to what might be unfolding with other people.’ The work expands on Boyce’s ‘Devotional Collection’, an ongoing archive project begun in 1999 which celebrates and brings into focus Black British female musicians, many of whom have been underacknowledged. The project has featured in exhibitions including a retrospective of Boyce’s work at Manchester Art Gallery in 2018.

For nearly forty years, Boyce has consistently worked within the art school context where she has made invaluable contributions to reshape the discourse of art through her work as an academic. Since 2014 she has been a Professor at University of the Arts London, where she holds the inaugural Chair in Black Art & Design. A three-year research project into Black Artists and Modernism culminated with the 2018 BBC Four documentary ‘Whoever Heard of a Black Artist?’, exploring the contribution of overlooked artists of African and Asian descent to the story of Modern British art. She holds three honorary doctorates from the Royal College of Art (2019), the Courtauld Institute of Art and Birmingham City University (2023), and an honorary fellowship from Norwich University of Arts (2022).

Boyce’s work is held in the collections of Tate, London, UK; Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK; Arts Council Collection, London, UK; The Government Art Collection, London, UK; British Council Collection, London, UK and Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, UK.

Boyce has been the recipient of numerous awards. In 2024, the artist received an DBE for services to art in the Queen’s New Year Honours List. In 2016, Boyce was elected a Royal Academician, and received a Paul Hamlyn Artist Award. Between 2012 and 2017, Boyce was Professor of Fine Art at Middlesex University and since 2014 she has been Professor at the University of the Arts London. As the inaugural Chair of Black Art & Design she led on a three-year research project into Black Artists & Modernism, which led to a BBC documentary Whoever Heard of a Black Artist? Britain’s Hidden Art History (2018).

Current Exhibitions

1 / 12