Essays

Friendship as a Way of Life

A consideration of the collective and individual work of fierce pussy

By Ksenia M. Soboleva

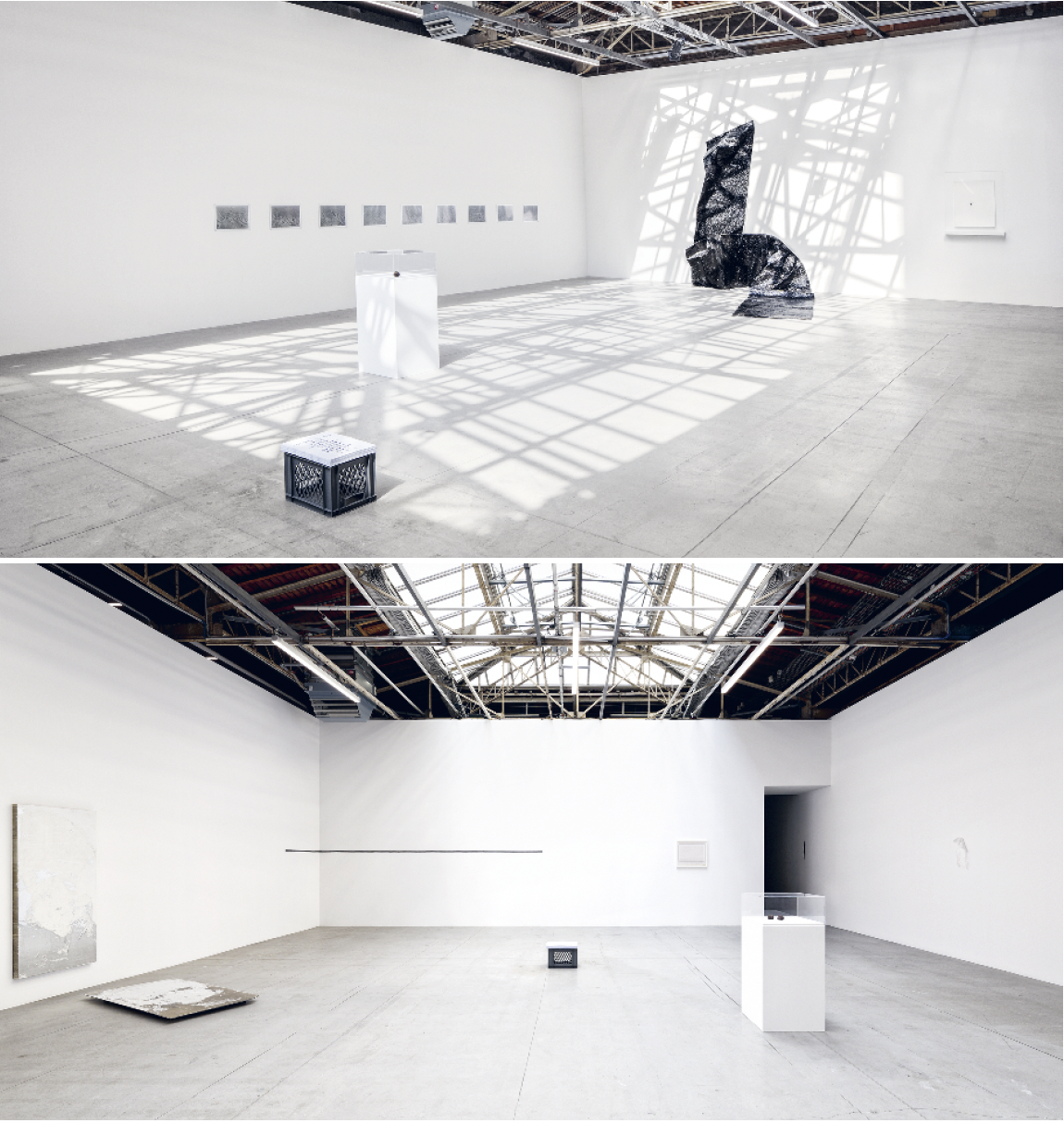

Views of “arms ache avid aeon: Nancy Brooks Brody / Joy Episalla / Zoe Leonard / Carrie Yamaoka: fierce pussy amplified, Chapter 7” at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2023. Photos: Benoît Fougeirol (top); Aurélien Mole (bottom). Courtesy the artists

In 1981, the same year that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released its first official report about the disease that was later to become known as AIDS, a quietly profound interview with Michel Foucault appeared in the French magazine Gai Pied. In the article, titled “Friendship as a Way of Life,” Foucault suggests that homosexuality— though today he likely would have used the term “queerness”—is not so much the sexual identity of an individual but rather the network of relations that emerges from a queer way of life. “The problem is not to discover in oneself the truth of one’s sex,” Foucault says, “but, rather, to use one’s sexuality henceforth to arrive at a multiplicity of relationships.” These relationships are the real threat that queerness poses to heteronormative society, he continues: “To imagine a sexual act that doesn’t conform to law or nature is not what disturbs people. But that individuals are beginning to love one another—there’s the problem.”

The AIDS crisis gave rise to an unprecedented multiplicity of queer relationships, broader and more complex than those that formed around the gay liberation movement of the 1960s. Queer people across the gender spectrum came together like never before to fight misinformation and spread awareness about the epidemic. ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), founded in 1987, became the largest organization to draw attention to the political nature of the health crisis. While not without its flaws, it provided a particularly effective platform for activists to establish connections, fueled by friendship and a common cause. The floor of ACT UP was a space of exhilaration and exhaustion, desperation and desire, crying and cruising.

Zoe Leonard, Two Oranges, 1992. Two oranges, thread, wax. Dimensions variable. Photo: Aurélien Mole. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galerie Gisela Capitain

Carrie Yamaoka, Skin, 2021. Flexible urethane resin and white pigment. Photo: Carrie Yamaoka. Courtesy the artist, Commonwealth & Council and Ulterior

Various smaller collectives surfaced around ACT UP, usually dedicated to issues not sufficiently addressed by the larger coalition. The collective fierce pussy connected in 1991 as a group of lesbian artists dedicated to advocating for greater lesbian visibility. Its founding members—Nancy Brooks Brody, Joy Episalla, Zoe Leonard and Carrie Yamaoka—constituted part of a larger assembly that gathered through an open call on the floor of ACT UP. Despite experiencing the increased homophobia, government neglect and mental health complications brought about by the crisis, lesbians were long left out of activist discussions and media coverage of the epidemic, due largely to the misconception that lesbians were immune to HIV infection (a fallacy rooted in the desexualization of lesbian identity in general and ignorance surrounding risk practices pursued by some lesbians, including intravenous drug use.) In his seminal 1987 essay “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic,” Douglas Crimp astutely proposed that the question gay men should be asking is not “What are lesbians doing to help us,” but rather “What are we doing to help lesbians?”

The first fierce pussy meeting took place at the Lower East Side apartment of Zoe Leonard, who was also part of a group that collectively wrote the Women, AIDS, and Activism handbook, published by South End Press in 1990. The fierce pussy collective decided to bring lesbian identity directly to the streets and came up with a series of “list posters” as its inaugural project. Taking possession of derogative and stigmatized terms such as “butch,” “dyke” and “bulldagger,” fierce pussy set out to reclaim language that had been weaponized to injure. Listing words in a column and placing “I AM” at the top and “PROUD” at the bottom, the collective transformed slurs into powerful affirmations of collective identity and sexual being, wheat-pasted throughout New York City—embodying a dynamic described by Judith Butler in reference to queer activism of the 1990s: “Performing excessive lesbian sexuality and iconography that effectively counters the desexualization of the lesbian.” The collective collaborated on projects until 1994, developing a distinct low-tech aesthetic that frequently paired image and text. Despite a connection to Condé Nast (Episalla and Yamaoka both held day jobs at the publishing company), fierce pussy notably rejected the agit-prop appropriation of glossy advertising imagery that became popular with some collectives of the period, resisting a culture of celebrity and media that would give rise to “lesbian chic” in the early 1990s. The collective’s view of the phenomenon was not equivocal. Many of their posters were printed surreptitiously on a Condé Nast copy machine; one poster declared: “LESBIAN CHIC MY ASS. Fuck 15 minutes of fame. We demand our civil rights. Now.”

Alongside their collaborative projects, fierce pussy’s members maintained individual studios and active lives outside the collective. They shared and diverged, grew together and apart, fell in love, fell down and often fell back onto each other. Amid the emotional exhaustion that caught up with many activists by the mid-1990s, fierce pussy went on a hiatus in 1994, though various members continued to collaborate on activist projects, primarily anti- Bush campaigns. The group officially reunited in 2008 when invited to participate in a “semi-retrospective” hosted by Printed Matter, and the four founding members have been making collaborative work under the fierce pussy banner ever since.

Portrait of the four core members of fierce pussy collective (from left to right: Carrie Yamaoka, Joy Episalla, Nancy Brooks Brody and Zoe Leonard), 2014. Photo: Alice O'Malley

In a pivotal piece of queer scholarship in 2003, Ann Cvetkovich uses the phrase “archives of feelings” to discuss trauma, sexuality and lesbian public cultures. I decided to write a dissertation about art, AIDS and lesbian identity in large part because I wanted to apply this phrase to artworks, being possessed of a sentimental self-interest (possibly jump-started by heavy doses of Russian poetry at an early age) in wanting to know what it felt like to be a lesbian at a specific time and in a specific place.

When I first interviewed the fierce pussy members for a paper I was to deliver at a conference on “constellations, clusters and networks” at Concordia University in Montreal in 2015, I frankly had trouble containing my nerves. Fresh to New York from Amsterdam, with little sense of queer community beyond myself, I was awed and intimidated by the group’s embodiment of collectivity. Episalla mentioned that the group had just been approached by artist and curator Jo-ey Tang, who was interested in finding ways to put the members’ individual works in conversation with each other and with the work of the collective, neither of which had been done before. An open-ended dialogue with Tang led eventually to “arms ache avid aeon: Nancy Brooks Brody / Joy Episalla / Zoe Leonard / Carrie Yamaoka: fierce pussy amplified,” an exhibition and publication project that has unfolded over multiple “chapters”—to use Tang’s terminology— since 2018. The alliteration of the project title is drawn from a piece by Yamaoka titled A is for Angel (1991), for which she plucked four “a” words from correction ribbons she had sourced from friends’ typewriters.

Resisting any static tendencies of exhibition- making and also art history’s instinctive fetishization of chronology, Tang envisioned a structure nonlinear in concept and presentation: Artworks from the late 1980s to the present were installed in varying iterations, with pieces reappearing in different chapters like unexpected but welcome guests. The first four chapters took shape over four months in late 2018 and early 2019 at the Beeler Gallery at the Columbus College of Art & Design in Ohio. In the first chapter, Brody, Episalla, Leonard and Yamaoka each had a room to themselves. A fifth was reserved for a fifth “artist,” fierce pussy itself, and contained ephemera and archival materials from the collective’s projects. While a dedicated archive room for fierce pussy was retained for the next three chapters, the other rooms presented a tangible dialogue between the four members. In the fall of 2019, a fifth chapter was realized at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, in keeping with the queer rules of the first four. Chapter six, to take the form of a book published in collaboration with Dancing Foxes Press, remains in the works.

fierce pussy, For the Record, 2013-23. Newsprint wheatpasted to windows at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2023. Photo: Aurélien Mole. Courtesy the artists

The first four chapters of the project were gone before they even reached my awareness, stuck as I was in the bubble of graduate school. When chapter five took place in Philadelphia in 2019, I was in Paris for a research residency and unable to make the trip to see it. When I discovered that chapter seven would unfold at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, as part of the “Exposé·es” exhibition inspired by Elisabeth Lebovici’s book Ce que le sida m’a fait [What Aids Has Done to Me] (2017), I decided there was no way I would miss it. Thinking about the project’s nonlinear premise, I felt that perhaps it was fitting that the seventh chapter would be my first, and so I traveled to Paris in March 2023.

I’d met Lebovici a few years prior during the research residency in Paris. With Google Translate supplementing my mediocre French, I’d made my way through her book, which discusses the ways in which everything and everyone has been affected by the AIDS crisis. Her chapters, like those of Tang’s, adhere to no linear narrative; they can be read out of order, from end to beginning. I had been particularly struck by Lebovici’s observation that “it is in the oral—and not written—archives of the fight against AIDS that we have seen that lesbians have been there since the beginning, that they have accompanied the mourning and the struggles.”

This sentiment strongly informed my dissertation project, to write about the lesbian experience of the AIDS crisis. Yet I still remember Lebovici telling me, as we shared an afternoon coffee, that for many years she had felt as if she were not allowed to write a book about her experience of the AIDS crisis because she had survived it. The guilt of survival is one the most complex emotions simmering in the aftermath of collective trauma. Cvetkovich writes that one “outcome of AIDS activism for lesbians is that they have a legacy; they have the privilege of moving on because they have remained alive.” When I read this early on in my dissertation research, the comment made perfect sense to me. Yet the more I spoke to artists who had lived through the epidemic, the more the equation between remaining alive and moving on didn’t sit quite right. Eventually, I found this discomfort articulated in an essay by David Deitcher, titled “What Does Silence Equal Now?” Building on ideas put forth by the psychologist Walt Odets about the “deification of survival,” Deitcher writes that “survival must mean something more than just staying alive; it must include the capacity for love, intimacy, and a sexual expression of such feelings.”

Nancy Brooks Brody, Opening Body, 1991 (detail). Pencil and ink on paper. Photo: Jenny Gorman. Courtesy the artist

Nancy Brooks Brody, Cubes, 2022. Wire and tape. Courtesy the artist

When I enter the Palais de Tokyo, I encounter a calculus of survival in countless manifestations, first as a large window installation of fierce pussy’s For the Record (2013–23), a project that explores the process of mourning as an ongoing and lifelong experience. Executed in black font are sentences that describe daily activities and quiet observations of mourning, such as: “if he were alive today, he’d be standing next to you” and “if they were alive today they’d know exactly what to say.” Interspersed between these conditional clauses are reminders that the person in question would “still be living with AIDS,” an ongoing epidemic. The word “AIDS” is executed in red, demanding attention. Translated into French by Lebovici’s partner, the writer Catherine Facerias, the bilingual iteration at the Palais de Tokyo (which stands in for the fierce pussy archival room seen in other chapters) is somewhat more difficult to decipher than previous iterations of this project, from which I’ve built a collection of postcards and posters over the years. In Paris, the text is continuously interrupted by the window structure, which disrupts the process of reading. Yet I find myself captivated by this disruption— it underscores the painful fact that we don’t know what the subjects of these sentences would be doing if they were alive today. The only thing we can know for certain is that they’d still be living with AIDS. The rest is purely speculative.

Making my way through the expansive exhibition over the course of five hours, I save the arms ache avid aeon gallery for last, the same way I’ve saved it for last in this piece of writing. As I step into the room I feel a palpable shift in my body, a renewed awareness. Sunshine filters through the skylight, casting shadows that follow my movements. To my right, a drawing by Brody depicts a figure tearing open its torso to expose a gaping void (Opening Body, 1991). “Here it is,” I think to myself, “here is my archive of feelings.”

Brody is the first artist I ever interviewed about her experience of the AIDS crisis, in 2014. She told me that “ACT UP New York: Activism, Art and the AIDS Crisis, 1987–1993,” an exhibition organized by Helen Molesworth and Claire Grace in 2010, was the first moment when the four fierce pussy members realized they had never taken the time to mourn their own losses. Many activists have noted a seeming absence of grief within the AIDS movement, in part because grief was equated with taking time when there wasn’t any to waste. I look to my left at four intricate cubes seemingly floating off the wall, Brody’s Cubes (2022), installed vertically and consisting solely of wire and tape, and I see an outline of both absence and volume. Elsewhere, she has literally filled the architectural structure with a new presence. Spanning a corner of the gallery, where two walls meet, is a twentyfoot horizontal metal line carved out and embedded into the wall (20 Foot Line, 2018–23), functioning like a stitch that holds the space together.

The notion of the body emptied and stitched back together runs through the chapters and resumes at the Palais de Tokyo. Leonard’s Two Oranges (1992), which formed the beginning of her larger, well-known piece Strange Fruit (1992–97), rests in a display case off to the side of the room. After the death of her friend David Wojnarowicz in 1992, Leonard began sewing back together scraps of discarded fruit peels, a process both reparative and futile. The piece became an homage to Wojnarowicz, recalling his sculpture of a loaf broken in half and sewn back together with red thread (Bread Sculpture, 1988–89), as well as the iconic image of the artist with his lips sewn shut (A Fire in My Belly, 1986–87). The shriveled and deformed fruit (notably embodying a term that is also a slur for “queer”) conjures the decaying body, the thread suggesting an effort to hold on.

Carrie Yamaoka, A is for Angel, 1991 (detail). Letraset and rubber cement on vellum. Photo: Stephen Takacs. Courtesy the artist, Commonwealth & Council and Ulterior

Joy Episalla, foldtogram (35'-2.5"x 44"- August, Iteration 7), 2018-ongoing (detail). Silver gelatin object/ photogram on RC paper. Photo: Benoît Fougeirol. Courtesy the artist and Tibor de Nagy

On the gallery’s south-facing wall, subject to a particularly striking shadow pattern as I walk toward it, stretches a passage from Leonard’s recent Al río / To the River (2016–22) project. A poetic investigation of the ways in which a river is used to perform a political function, the photographs explore the Rio Grande (called the Río Bravo in Mexico) as both a border and an entity that abides no borders. The nine photographs on view show the river whirling and swirling, the surface wrinkles reminiscent of skin. I cannot help but see clitoral shapes in these photographs, possibly because elsewhere in the exhibition Leonard has showcased archival materials from an installation she created for Documenta IX, in 1992, in which she famously juxtaposed 18th-century portraits of women from the permanent collection of the Neue Galerie in Kassel, Germany, with nineteen close-up shots of her friends’ vulvas. A new series of these pussy prints, created specially for “Exposé·es” and hung throughout the exhibition (Untitled, Palais de Tokyo [for Elisabeth]), 2023), both activates and seals this history.

If history is a scab, Yamaoka is determined to scratch it. Intrigued by what happens when one doesn’t follow a medium’s technical protocols, she experiments continuously with the unpredictable nature of material behavior, rubbing and peeling reflective surfaces, reinterpreting spaces of presumed error as spaces of serendipitous potential. She often returns to older pieces and reworks them, challenging the idea that artworks are fixed in time. Elsewhere in the gallery, a thin sheet of white urethane resin, Skin (2021), hangs like a mask freshly peeled off a face, the body implied by its absence.

Zoe Leonard, Al río / To the River, 2016-22, Gelatin silver prints, C-prints and inkjet prints. Photo: Aurélien Mole. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galerie Gisela Capitain

fierce pussy, AND SO ARE YOU, 2008. Freely distributed posters. Courtesy the artists

Episalla’s foldtogram (2018–ongoing) unrolls into the space like an eager tongue, revealing a landscape of cracks across a surface of silver gelatin. Reappearing in different iterations in all the chapters thus far, like Brody’s 20 Foot Line, the piece both archives and resumes the chapters. Episalla creates these colossal prints in the darkroom without the use of a camera, to explore photography’s sculptural quality and also to closely study traces of touch. A smaller, adjacent room houses a projection of Episalla’s new film, As long as there’s you, As long as there’s me (2023). The film consists of footage Episalla shot over eighteen years, documenting both people and animals performing without realizing that anyone is watching— a non-performative performance.

The scholar Sara Ahmed once wrote that “individual struggle does matter; a collective movement depends upon it.” If the collective practice of fierce pussy is direct and explicit, the individual works of Brody, Episalla, Leonard and Yamaoka are subtle and quiet, offering a different kind of lesbian visibility, one that escapes bodily representation and instead manifests itself through friendship as form in proximity and dialogue. Much of the work suggests that there’s a limit to what the body, punctured by loss, can contain before it cracks open and grief inevitably seeps in. Yet the process of cracking by definition gives rise to a multiplicity. Though I am the only person in the gallery, I can feel another presence—that of time as a body—softly breathing down my neck, a sense of time expanding and collapsing simultaneously. An empty crate whose purpose I can’t decipher sits uncomfortably in the room with me. I later learn that it’s supposed to hold a stack of list posters, all taken for the day, and I’m overcome by a kind of sweet disappointment, having lost something I didn’t have—missing the opportunity to take away a tangible record of my presence and having to rely on the embodied memory alone.

-

Dr. Ksenia M. Soboleva is a New York-based writer and art historian specializing in queer art and culture. She holds a PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, BOMB, The Brooklyn Rail and many other publications. She is currently co-editing the first monograph on the 1990s lesbian gallery and project space TRIAL BALLOON. Soboleva was a Vilcek Curatorial Fellow at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2020 and 2021 and is currently an Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral fellow in gender and LGBTQ+ history at the New York Historical Society.