Portfolio

Cut, Stack, Tilt, Twist, Turn, Repeat

Briony Fer on the radical aspects of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s abstraction

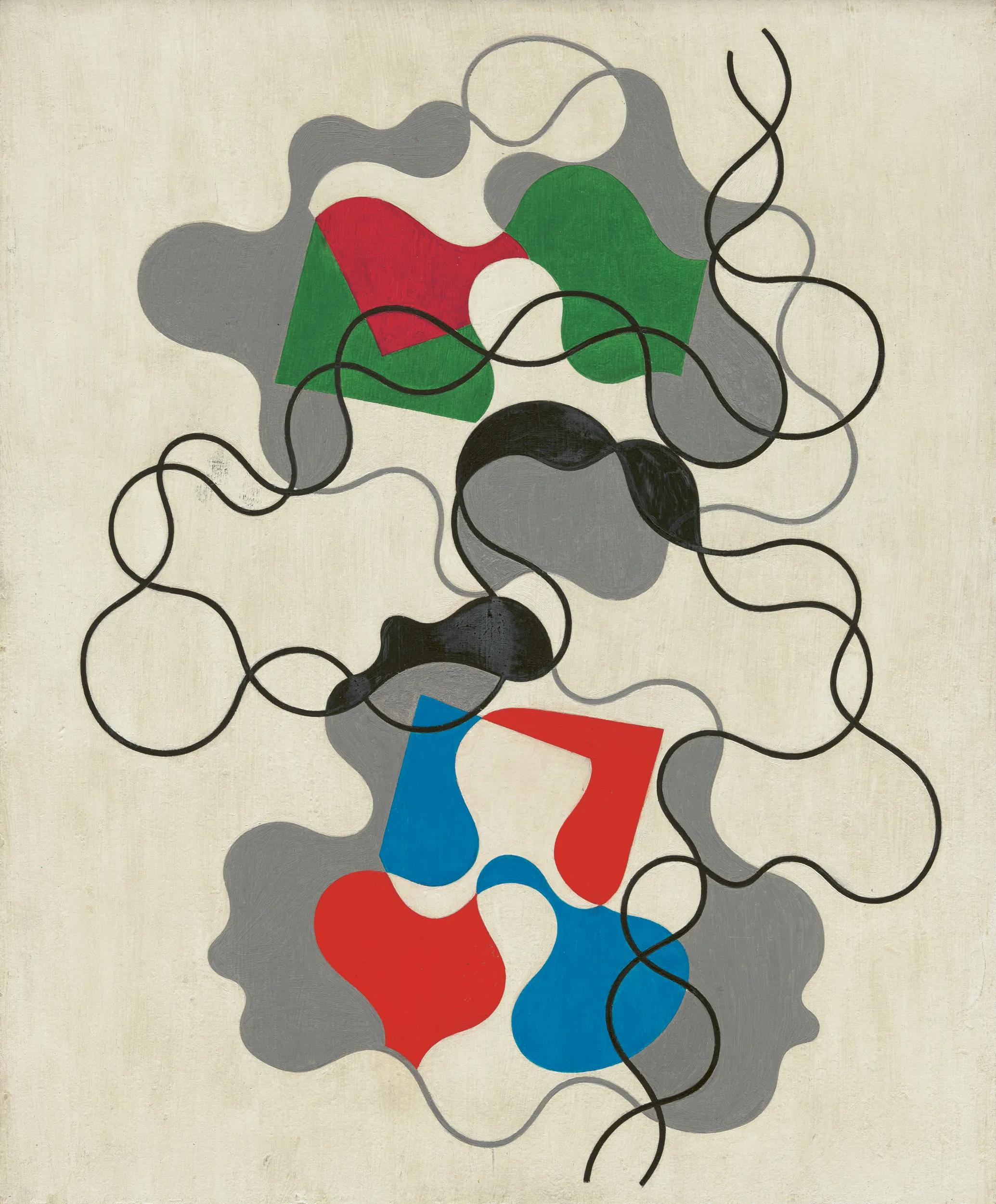

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Lignes d’été (Summer Lines), 1942 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Alex Delfanne

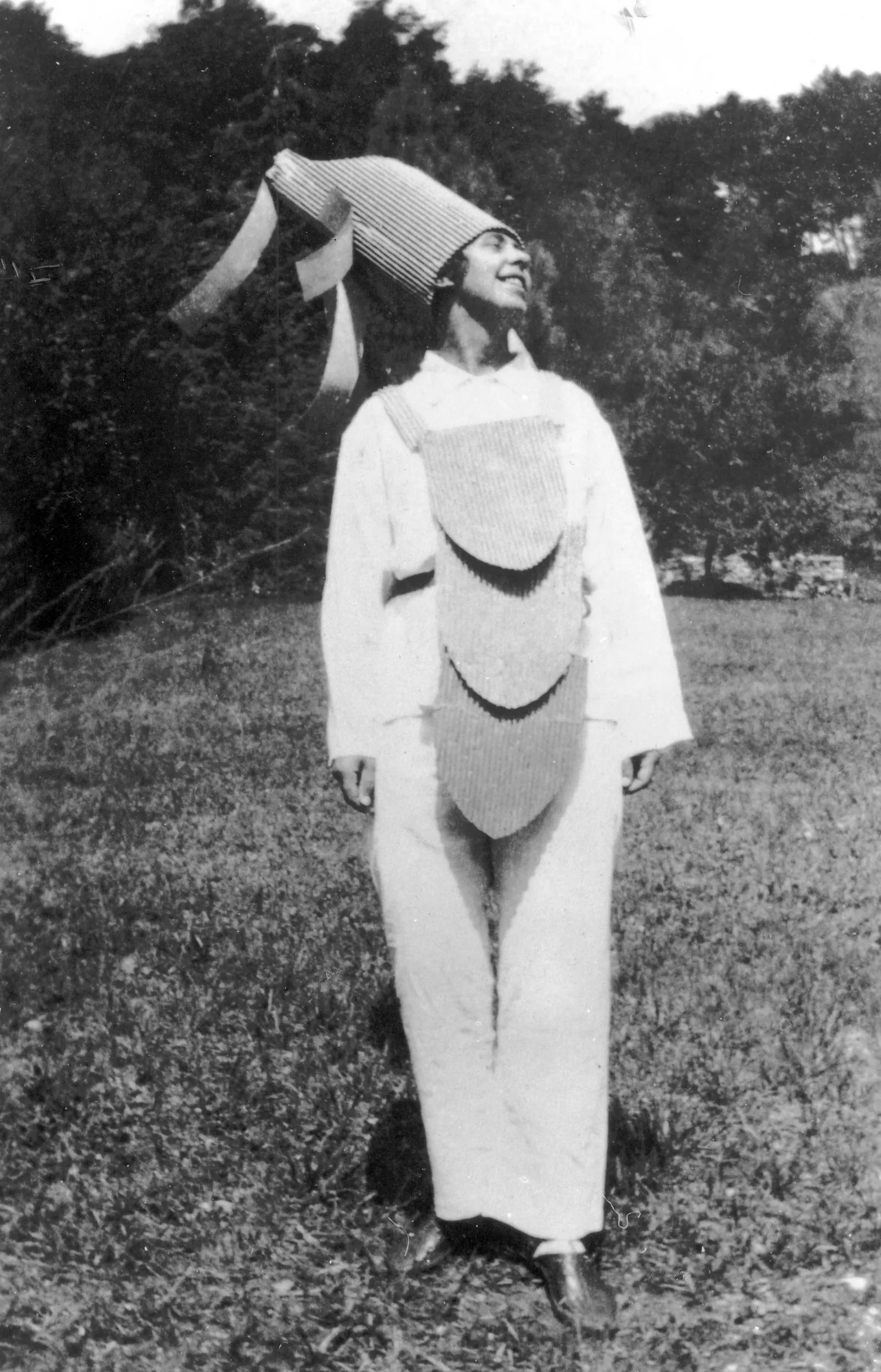

There’s a photograph of Sophie Taeuber-Arp taken just over 100 years ago in the late summer of 1925. She is at a party in Ascona, Swizerland, on Lake Maggiore, laughing in the sunshine, her ridiculously tall hat topped with streamers that fly back as she moves to turn her head in profile. The shapes hanging around her neck could almost be part of a medieval tabard made of corrugated cardboard. The tabard is body armor—Dada-style—protecting her in combat against past protocols, and it’s reminiscent of the wildly inventive costumes she made for her performances at Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. There’s something in the photograph that captures an almost euphoric sense of release, a relaxation of pressure, a sense of the future stretching ahead, of the possibilities of a new art, along with new techniques, adequate to the times Taeuber-Arp and her friends were living. She wears this bricolage over what looks like a worker’s boilersuit, making it feel like a carnivalesque riposte to the rationalism of the machine aesthetic prevalent at the time.

It’s precisely here—at this strange meeting point between Dada dissonance and the language of form associated with geometric abstraction—that I would like to place Taeuber-Arp. This is where she found herself, and rather than choose between the two paths before her, she abandoned neither. It reminds me of the baseball player Yogi Berra’s comic koan, oft-quoted by artist Mel Bochner: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Ascona, 1925 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth

It’s the odd, even quirky, elements in Taeuber-Arp’s formal vocabulary that hint at the paradoxical nature of her abstraction. Each of her works seems like a small puzzle containing at least one or two rogue elements, never quite corresponding to what “geometric abstract art” of the early 20th century is supposed to look like—that is to say, the paradigmatic structure of the grid, the regular geometric form, the primary colors and so on. Instead, we frequently come upon a small yet strangely extravagant decorative curl or arabesque protruding into the space of a painting. These kinds of forms, ornamental flourishes that enter the frame at various unexpected moments, seem to defy the very system of geometric abstraction that she, along with others, pioneered in the 1910s and 1920s.

Though Taeuber-Arp was a committed abstract artist, she flouted much of the accepted historical narrative of abstract art, confounding quite a few of the clichés that are still regularly rolled out by way of definition. First, the idea that abstract art is the opposite of figurative art and therefore lacks meaning. Her work frequently makes allusions to objects and figures in the world, and is irrevocably of it. Second, the hard-to-budge assumption that abstract form can be divided between the “organic” (that is, curvilinear) and the “constructive” (that is, rectilinear) is undermined in her work by the fact that much of it is without doubt both at once. She plays with form, as one might play with words, to create double meanings, using, for example, continuous contours to make a shape that is curved and rectilinear at the same time, deftly switching between positive and negative space. Because her lines, notably her outlines, are so fluent, the sense of dislocation becomes all the greater.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition dans un cercle (à volutes) (Composition in a Circle [with volutes]), 1938 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Éléments divers en composition verticale-horizontale (Diverse Elements in Vertical-Horizontal Composition), 1918 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Alex Delfanne

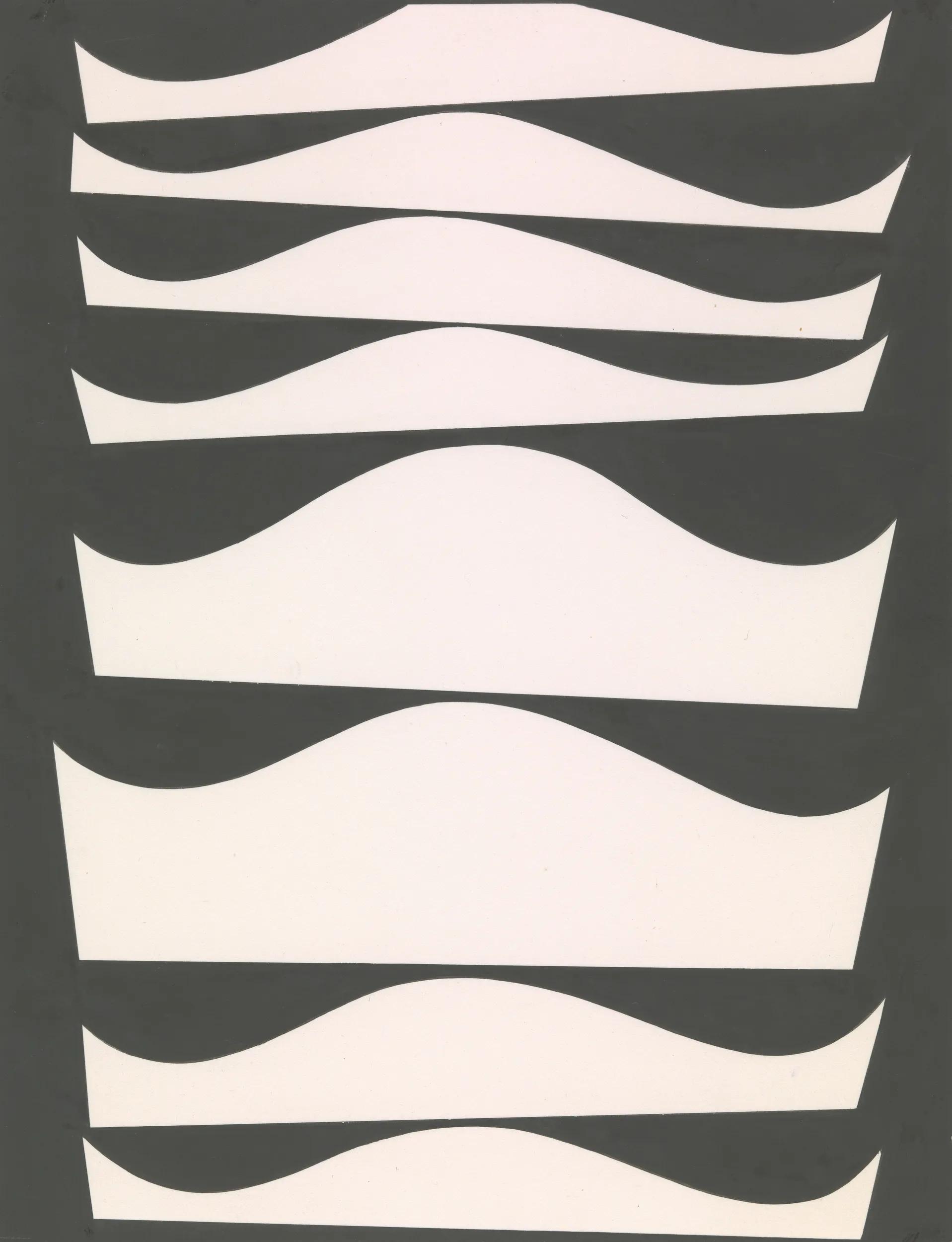

There’s a powerfully subversive sense of play at work here, even at the level of form. In her Échelonnement series (whose title roughly translates to “gradations” or “scalings”), outlines of irregular shapes, both curved and straight, seesaw precariously. This unstable movement doesn’t express transcendental absolutes but rather suggests a just-about-to-topple house of cards. The world falls around us, beginning gradually and gaining speed as the series proceeds. Her formal language contains a surplus of meanings and associations, suggesting that abstraction can’t keep the world out, nor should it; it is, if anything, too immersed in it.

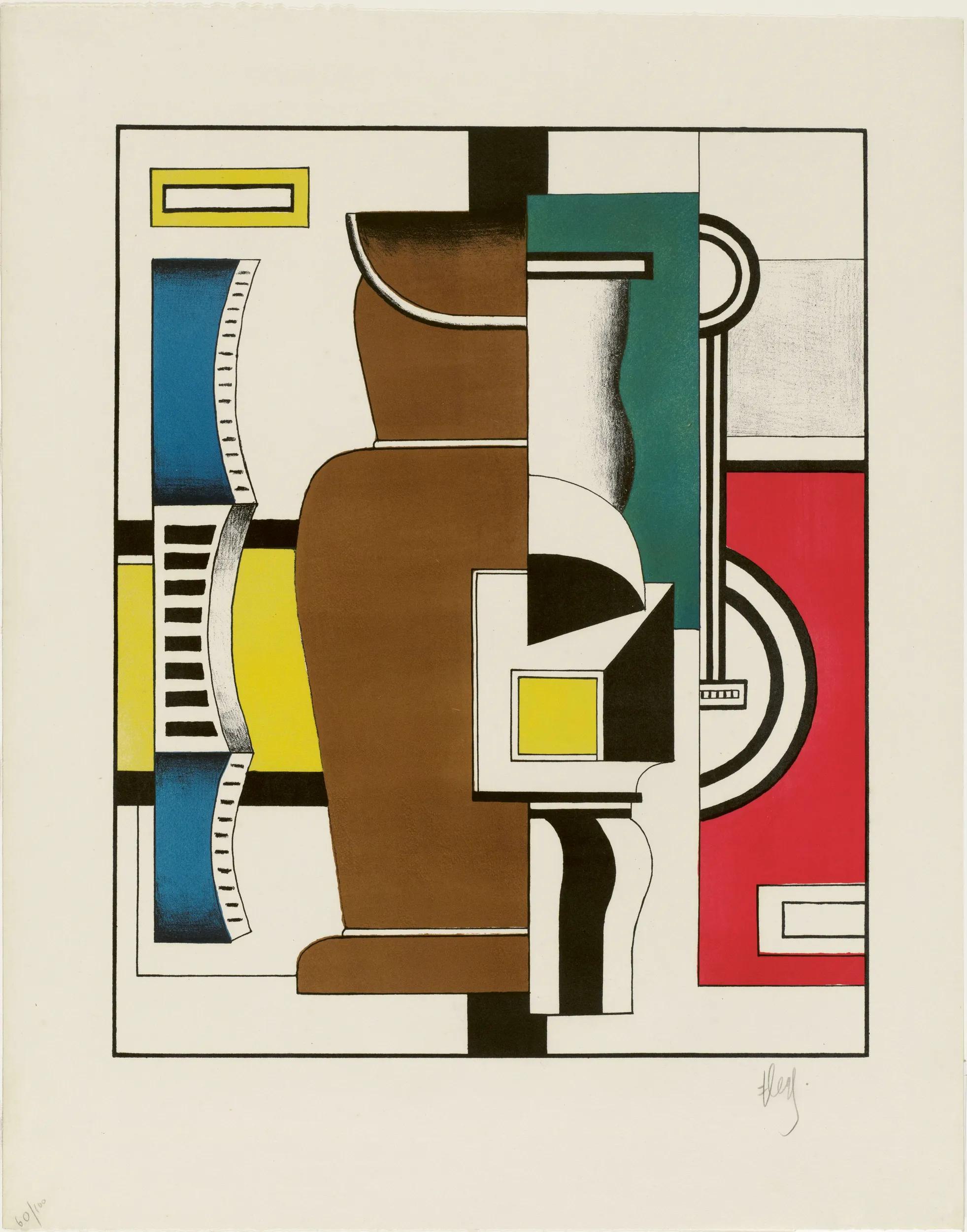

Taeuber-Arp takes elements from the apparently solid world of architecture and treats them as if they are in danger of dispersing. Remember that fleeting turn of her face in the photograph. “Profile” is the term we use for a side view of a face, and the broader meaning of the word suggests that a person’s character can be captured in a single, continuous line (think of Matisse). But the word has a more specialized meaning in architecture, where it refers to a cross-sectional view of a structure. Profiles of things and profiles of people are brought together by Fernand Léger who—and I can’t think of another artist in a similar vein—seems to want to confirm, through the solid-block colors and symmetry of a painting like Blue Guitar and Vase (1926), that the world can be relied upon. Taeuber-Arp’s profiles, on the other hand, feel more like temporary arrangements, or pieces in a pattern that haven’t quite found their final placement.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Échelonnement, (Gradation), 1934 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Plans profilés en courbes et plan (Planes Outlined in Curves and Planes), 1935 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection Kunstmuseum Bern

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition, 1935 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection Hamburger Kunsthalle/bpk. Photo: Christoph Irrgang

When she borrows the shape of an architectural profile in a scalloped curve, in works like Plans profiles en courbes et plan (1935), it is as if she wants to create a cross-section through the visual field of modernity, in the same way a molding or a cornice can be sectioned. At times, it seems she is reaching even farther back in history, to the strangeness of the “elements” of architecture, the basic templates of which we see in Jacques-François Blondel’s details from the beginning of the 18th century, or in dictionaries of ornament. In this sense, her formal references are not just anomalous but also deliberately archaic and anachronic.

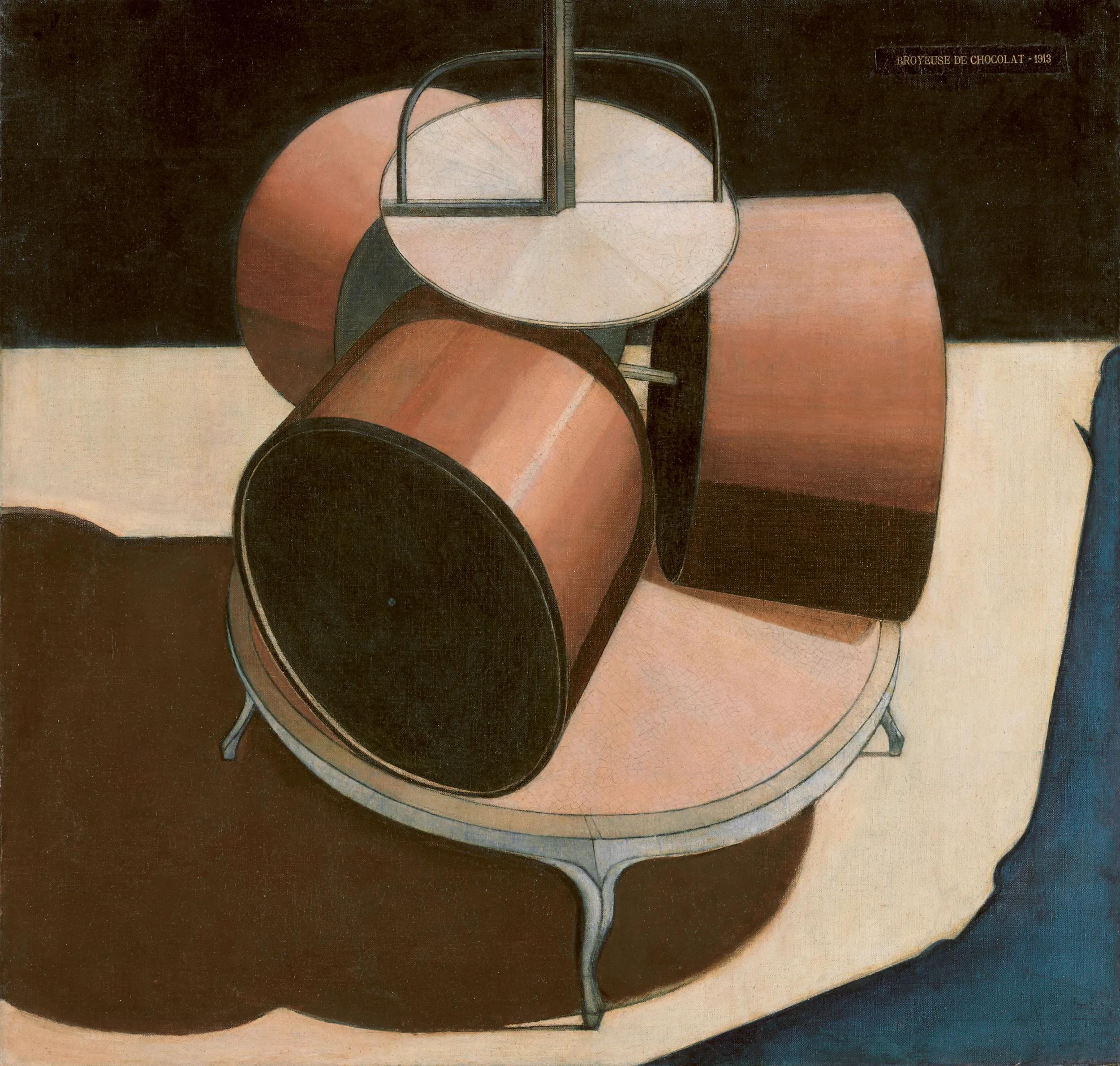

Unlikely as it may seem, Duchamp was one of the few commentators who understood her project. His entry about Taeuber-Arp in the 1950 catalogue for the Société Anonyme Collection at the Yale University Art Museum was the absolute antithesis of everybody else’s—contrasting especially with the writing of fellow artist Michel Seuphor, who claimed in orthodox terms that her work exemplified the spiritual mission of pure abstraction. Duchamp understood how Taeuber-Arp punctured precisely such grandiose claims of art’s transcendence. Her biggest innovation, he wrote, was her introduction of the geometric arabesque, long repressed as mere decoration, into abstraction. The only other artist to whom he attributes the use of the arabesque is Calder; he finds it traced in the movement of Calder’s mobiles on currents of air. Duchamp particularly admired the way Taeuber-Arp left nothing to the “hazards” of brushwork.

Jacques-François Blondel, Four Bracket Designs, ca. 1737–38. Courtesy Drawing Matter Collections

Fernand Léger, Le Vase (The Vase), 1927 © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

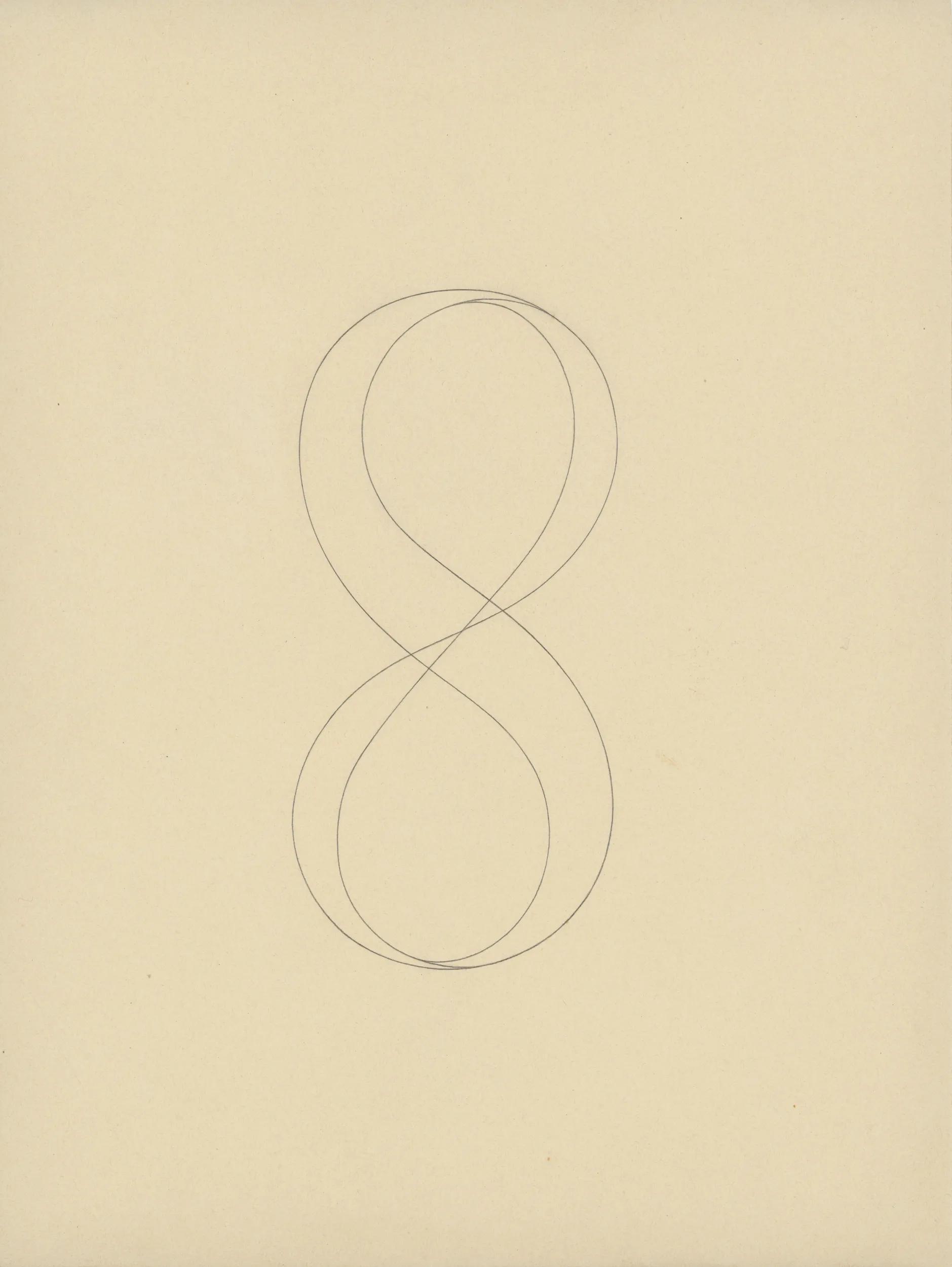

An untitled drawing she made in 1937 closely resembles a Möbius strip, a geometric structure that rotates 180 degrees without breaking. The drawing—perhaps it’s just a study—is provisional, a figure eight that turns on itself, flipping sides in a continuous movement. Such forms would surface again in her so-called last drawings, the Geometric Constructions made in 1942. These ink works have been seen as anomalous, final loose ends that pointed in a new direction—a direction that we will never know about (Taeuber-Arp died the following year). But she liked anomalies, and these late drawings might be understood as speculative reflections on her earlier round reliefs, reconsidered through the lens of her isolation during World War II. Certainly that early euphoric moment of hope at Ascona was a distant memory in the despairing days of wartime, even though she and her husband, Hans Arp, had managed to escape Paris for Switzerland.

What’s interesting is how Taeuber-Arp’s larger project of abstraction has been continued in the work of others, in response to very different circumstances. In recent examples, think of contemporary artists such as Leonor Antunes, Sonia Boyce and Haegue Yang, all of whom explicitly engage with Taeuber-Arp’s legacy. None are abstract artists in the way she was, but that’s not the point. Who could be? As contemporary artists, they suggest that there’s something more to be said about awkwardness, or maybe more generally about a desire to throw a spanner into the works—a desire that makes Taeuber-Arp oddly timely.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Construction géométrique (Geometric Construction), 1942 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Marcel Duchamp, Chocolate Grinder (No. 1), 1913. The Philadelphia Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2025

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Sans titre (Untitled), 1937–38 © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin / Rolandswerth / 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Alex Delfanne

–

“Sophie Taeuber-Arp. La règle des courbes / The Rule of Curves,” curated by Briony Fer, opens at Hauser & Wirth Paris on January 17, 2026.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp. La règle des courbes / The Rule of Curves will be released by Hauser & Wirth Publishers in February 2026.

–

Briony Fer has written and contributed to major publications including On Abstract Art, The Infinite Line and Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction, and co-curated “Anni Albers” at Tate Modern. She is a professor of the history of art at University College London and a fellow of the British Academy.