Diary

Up Country

A recap of the inaugural Ursula Weekender

All photos: James D. Kelly and Sim Canetty-Clarke

- Friday 2 May

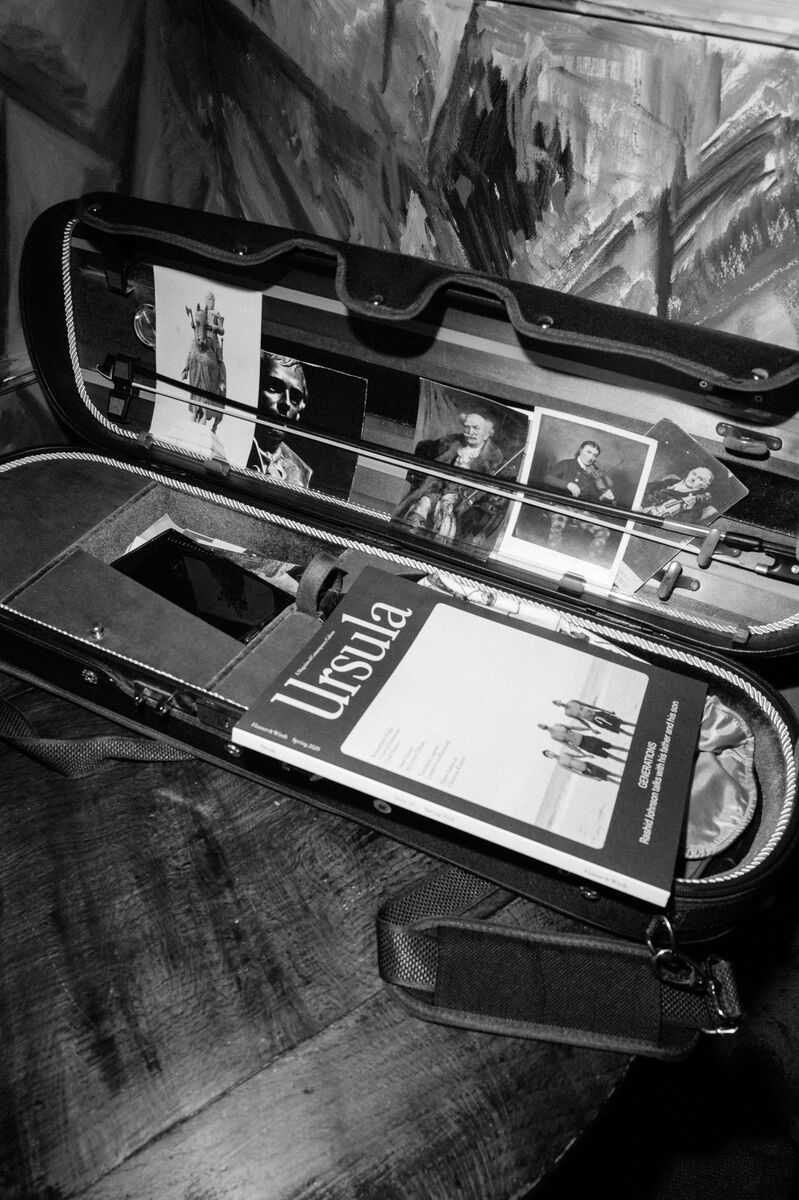

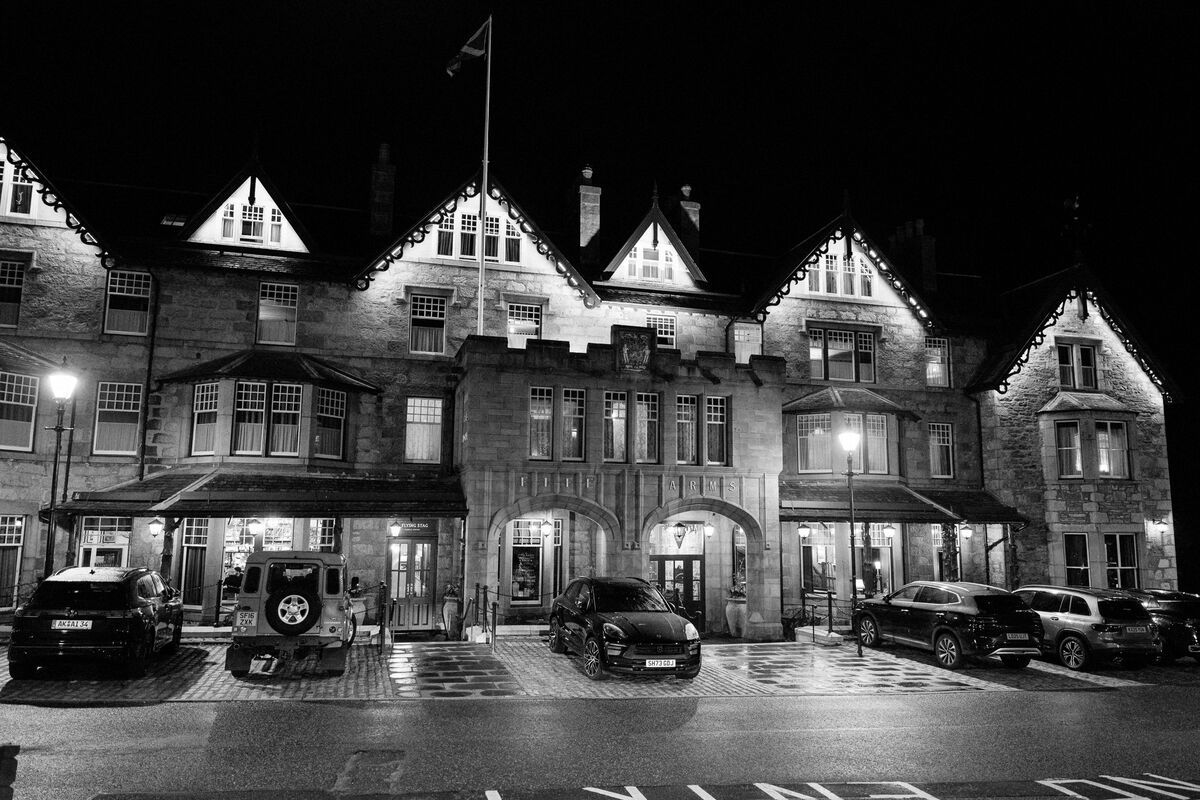

From April 25 through April 27, the inaugural Ursula Weekender, an unconventional cultural gathering, took place in the Scottish Highlands, bringing together artists, novelists, designers, architects, publishers, curators and other creative people to explore the spirit of Ursula magazine off the page, in the world. Unfolding at the Fife Arms hotel, the Braemar Village Hall and the historic landscape, the event asked the participants to join in reimagining what a cultural magazine can do in the 21st century. Below are some of the sights, sounds and ideas from the weekend.

Day 1

The evening began with a Ruinart champagne reception and a bagpiper playing the guests into to the Clunie Dining Room. At the close of the opening night’s dinner, poet and Booker Prize-winning novelist Sir Ben Okri stood to read a poem, “A History of New Forms,” published in the current issue of Ursula, an ekphrastic pairing with an untitled 2015 work by David Hammons, Okri’s longtime friend. Okri recounted his first meeting with Hammons in New York in 2014 and explained why, for him, Hammons’s work is particularly receptive to poetic response.

“I was at his studio and a couple of things caught my eye. I became aware immediately that he composes and decomposes, to quote Derek Walcott. He’s always playing with composing and decomposing. His studio has the appearance—in fragments, in sections, in isolated portions—of a freestanding poem.”

“I was at [Hammons] studio and a couple of things caught my eye. I became aware immediately that he composes and decomposes, to quote Derek Walcott. He’s always playing with composing and decomposing.”—Sir Ben Okri

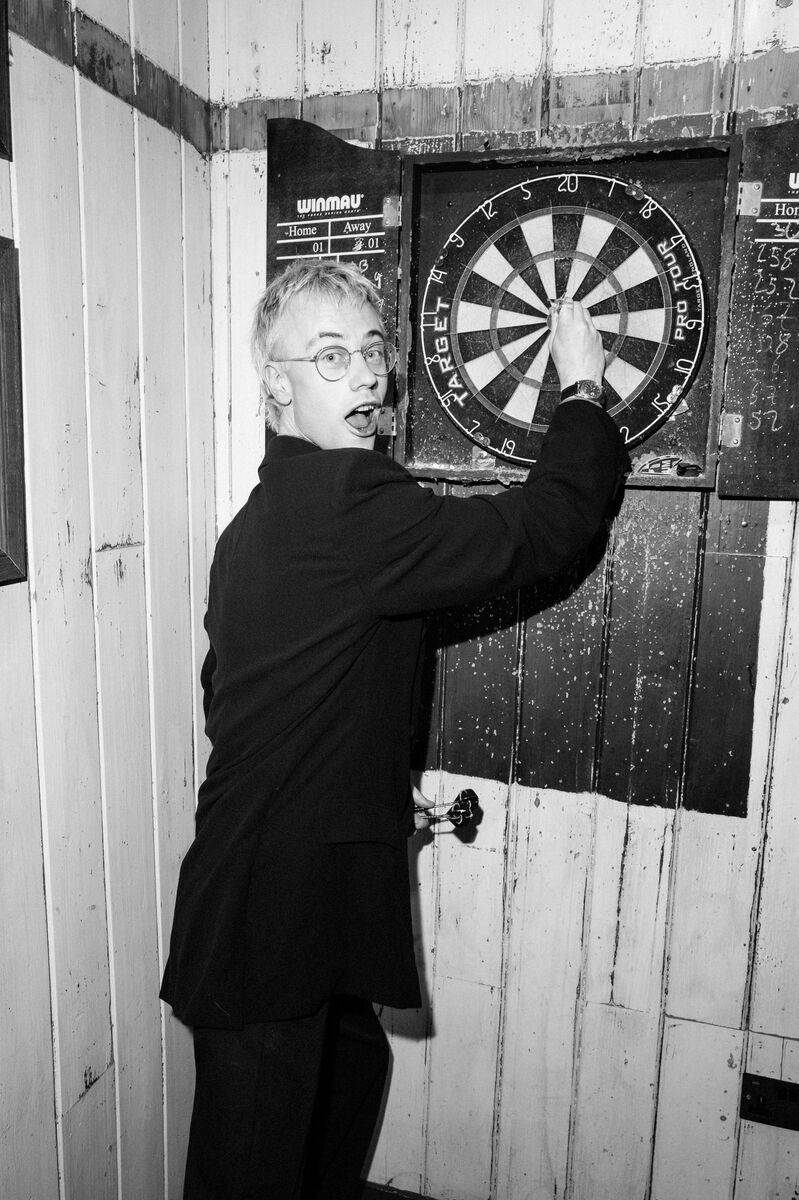

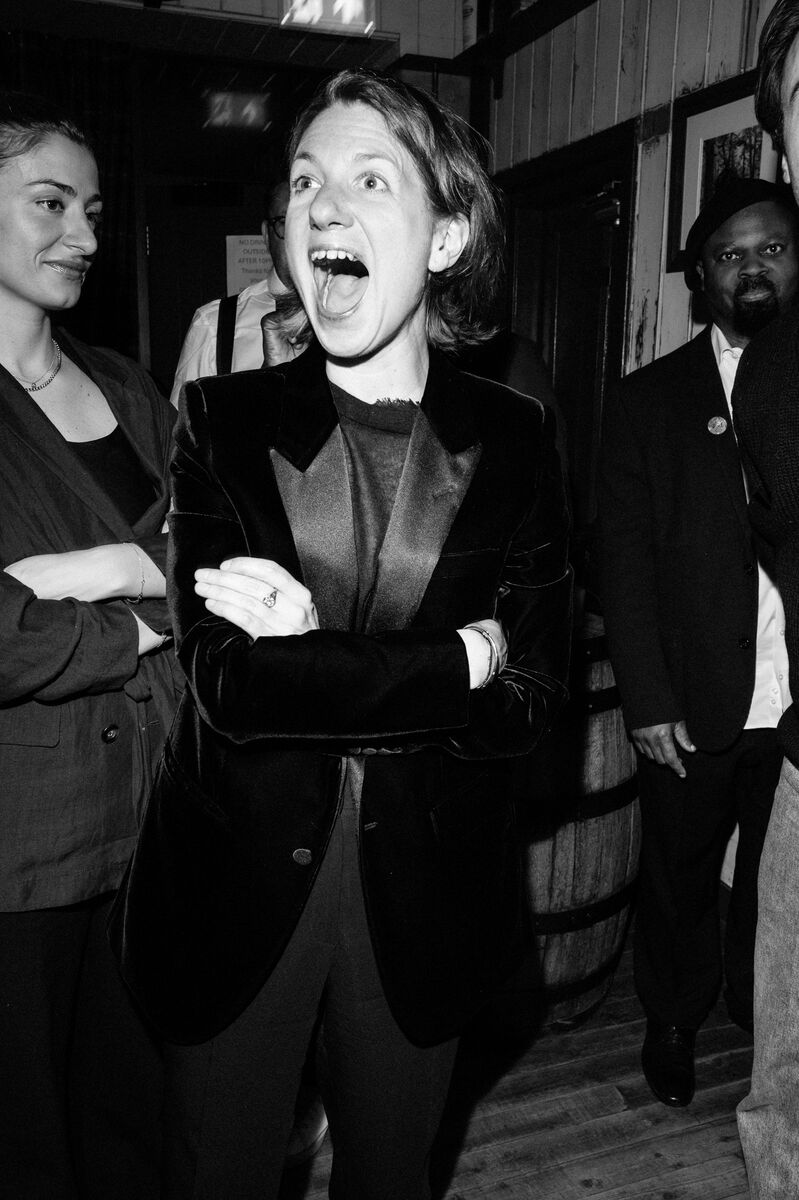

The night went into the wee hours at the Invercauld Mews Pub with a Dover Street Market ‘Lock-in’ featuring a playlist selected for the night by Jarvis Cocker, negronis from the Farm Shop and a few rounds of darts. A surprise bullseye brought the night to a close.

Sir Ben Okri

David A. Bailey, Dame Sonia Boyce and Ekow Eshun

Bee Emmott and Lorraine Grant

Neil Wenman and Randy Kennedy

Remo Hallauer

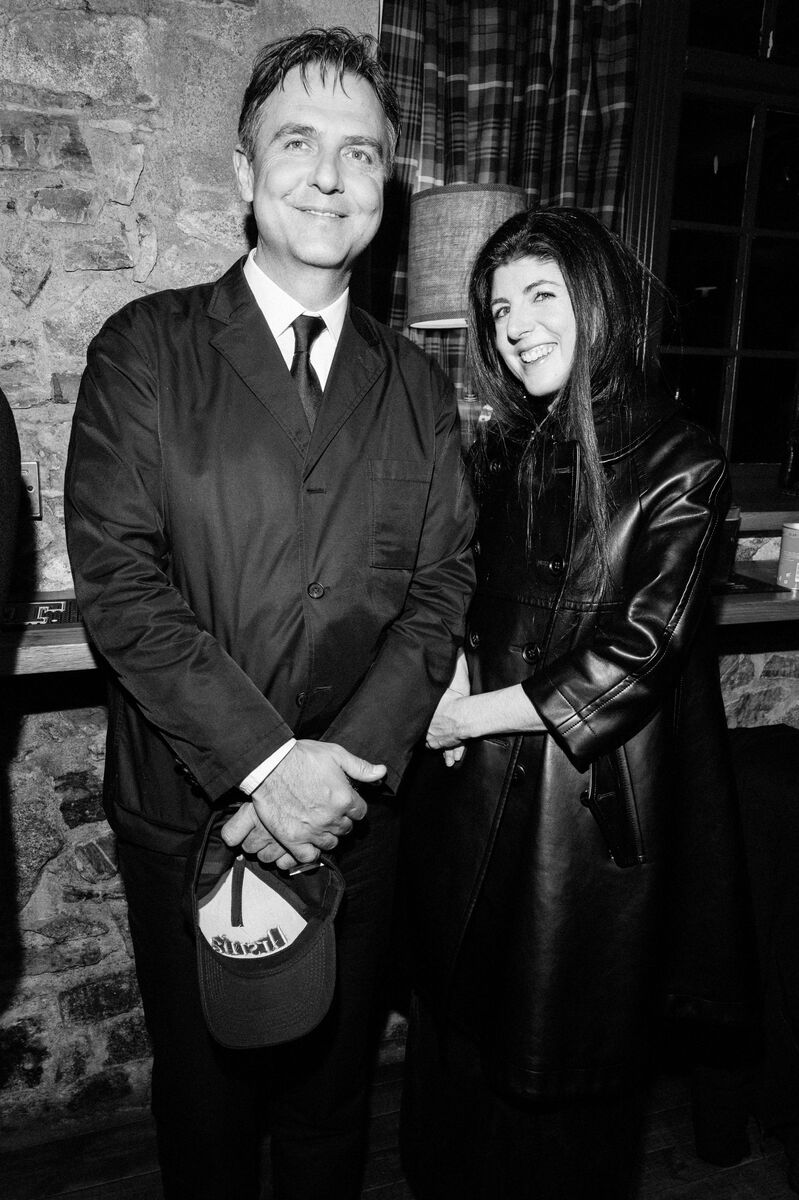

Dickon Bowden and Daisy Hoppen of Dover Street Market

George Rouy at the Invercauld Mews Pub

Cajame Chanter, Hannah Barry and Sir Ben Okri

Day 2

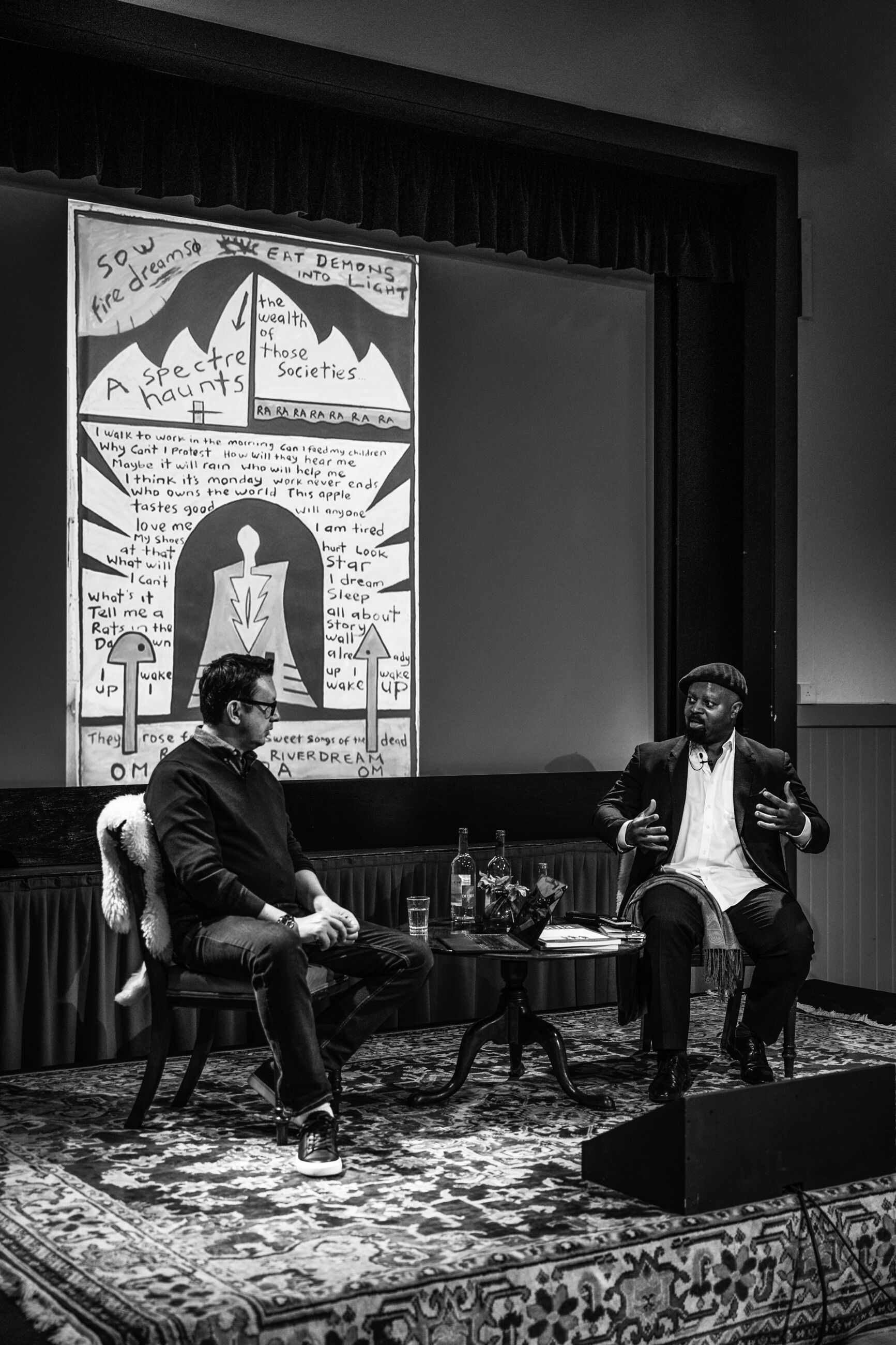

The Weekender’s second day began at the Braemar Village Hall, where Okri and Randy Kennedy, the editor in chief of Ursula, spoke about whether fiction and poetry still have the power to bring about political change and about the rituals of struggling with language.

Okri: “Writing is an arduous, hermetic, quantum experience. You go into the subatomic dimensions of narrative and of words. You really go deep. You go inside the tiniest aspects of a world. And from there you start to build things up. It’s very, very strange. I go off into this really difficult dream, and to pull myself back up from that is sometimes a bit traumatic. So I think of writing as both anguish and ecstasy at the same time. I used to write at night, which was easier. Now, I write in the morning. Very difficult. Very, very difficult. The blank page is blanker in the morning.”

Braemar Village Hall

Randy Kennedy and Sir Ben Okri

Randy Kennedy, George Rouy and Marco Capaldo

“How is it that we can sit and shut our eyes and think about how we feel as bodies, how the weight of our hands or the weight of our feet, the size of our heads feels in relation to the rest of our bodies, the rest of what’s around us?”—George Rouy

Following Okri, painter George Rouy and fashion designer Marco Capaldo of 16Arlington spoke about their friendship and their collaboration for Bodysuit, a new dance performance created by Rouy and choreographer Sharon Eyal, with costumes designed by Capaldo.

Rouy: “How is it that we can sit and shut our eyes and think about how we feel as bodies, how the weight of our hands or the weight of our feet, the size of our heads feels in relation to the rest of our bodies, the rest of what’s around us? I think the dance translates those kind of sensations within all of us. Even if we can’t dance, there’s a kind of knowing of movement that we all have. We can all imagine it. And I think what this piece is about is that strange awareness.”

Capaldo: “So much of Sharon’s work is focused on the form. So much of George’s work is focused on the form. And, for a designer, the body is our canvas, what we work around. So there was always the starting point of real simplicity for these costumes, to be as close to the body as possible. In the rehearsal process, what I really took from it was watching the dancers and studying their movements. Each one of them had very specific parts of their bodies that felt as if they jumped out. One was a calf muscle, one was a shoulder, one a bicep. So we created an embroidery that emphasized those parts of the body.”

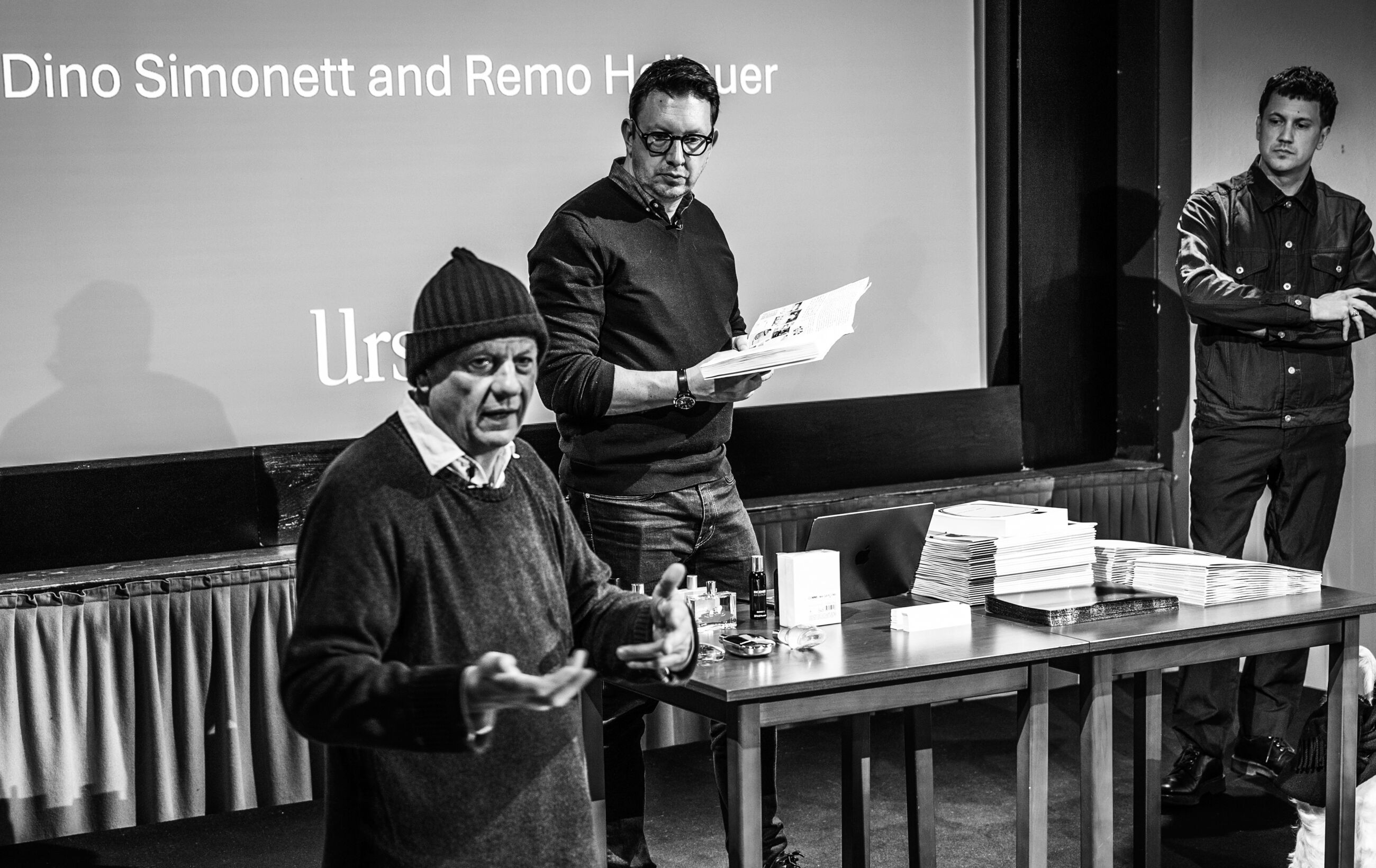

After lunch, Swiss book-publishing veteran Dino Simonett and Remo Hallauer, chief operating officer of Comme des Garçons, spoke about the creation of Comme des Garçons Parfums: 1994-2025, a wildly idiosyncratic art-book-meets-catalogue raisonné of the fashion house’s fragrances and their containers, bottles and boxes over three decades.

Hallauer: “Rei Kawakubo is a dedicated, longtime fan of books and printed matter and Adrian Joffe, our chief executive, is a huge poetry fan, which kind of brings me back to this morning’s talk with Ben Okri. It’s interesting to link it all together. Generally, Adrian writes the press release for our fragrances himself. And he tries to think in ways that a poet might. I think for the very first fragrance we launched, he wrote the phrase: ‘Works like a medicine, behaves like a drug.’ Phrases like that put you in the mindset of: ‘Okay, maybe this smell can actually change something.’”

Simonett: “I’m someone who always looks ahead, but I like to look behind sometimes as well. So in this case, it was amazing to me to find out what this company had created through the years. You might say it’s only perfumes, but the whole history of it was hyper-creative, really innovative. It had so much thoughtful and unexpected design in it—bottle design, graphic design. There was so much ephemera created around it. So working on this book was a bit like Treasure Island. Of course there is this irrational element with perfume. Everybody reacts differently to scent. It’s like reacting to poetry. It’s a highly individual thing. I’ve had various encounters already during this weekend. Someone comes up to me and says, ‘You smell good. What is it? What is it?’”

Dino Simonett, Randy Kennedy and Remo Hallauer

Dame Sonia Boyce

Dame Sonia Boyce and Ekow Eshun

As the culmination of the second day’s talks, curator and writer Ekow Eshun took the stage with the artist Dame Sonia Boyce, winner of the Golden Lion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, to talk about Boyce’s highly experimental use of collaboration in her work and how that collaboration has deepened over the years.

Eshun: “What I love in your work is that, as well as privileging the voices of the people you’ve worked with, there are so many other elements, found elements, all the stuff that would be called ephemera, which is another way of saying really just rubbish. Yeah, rubbish. But within rubbish sometimes there’s gold. You find it in your use of wallpaper, with album and CD covers that you use as readymades, with the promotional materials. You’ve given them all the space. You’ve given them all a voice.”

Boyce: “In 2017, for my show ‘We move in her way’ at the ICA in London, we did an element in their theater and we invited audience members to participate. I created a series of masks that people could wear. There were a lot of people in the room. Slowly, people began realizing they could join in this thing that was happening. There were very ephemeral kinds of sculptural objects that you could make noises with. At a certain point, the dancers left, but the audience was still playing. The crew packed up and people were still playing. The curator became a little bit anxious with me. She said: ‘So, when is it going to stop?’ And I said, ‘I really don’t know.’ And she was like, ‘But who’s in charge here?’ And I said, ‘Well, no one!’”

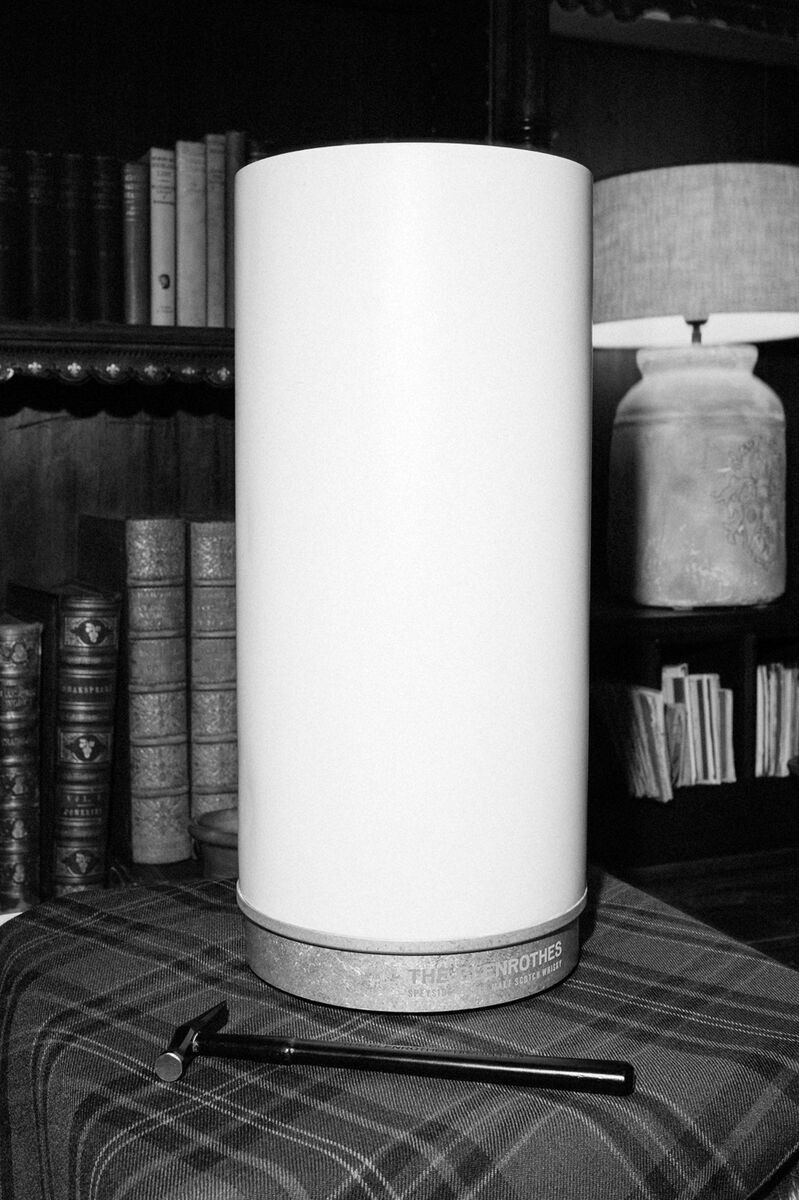

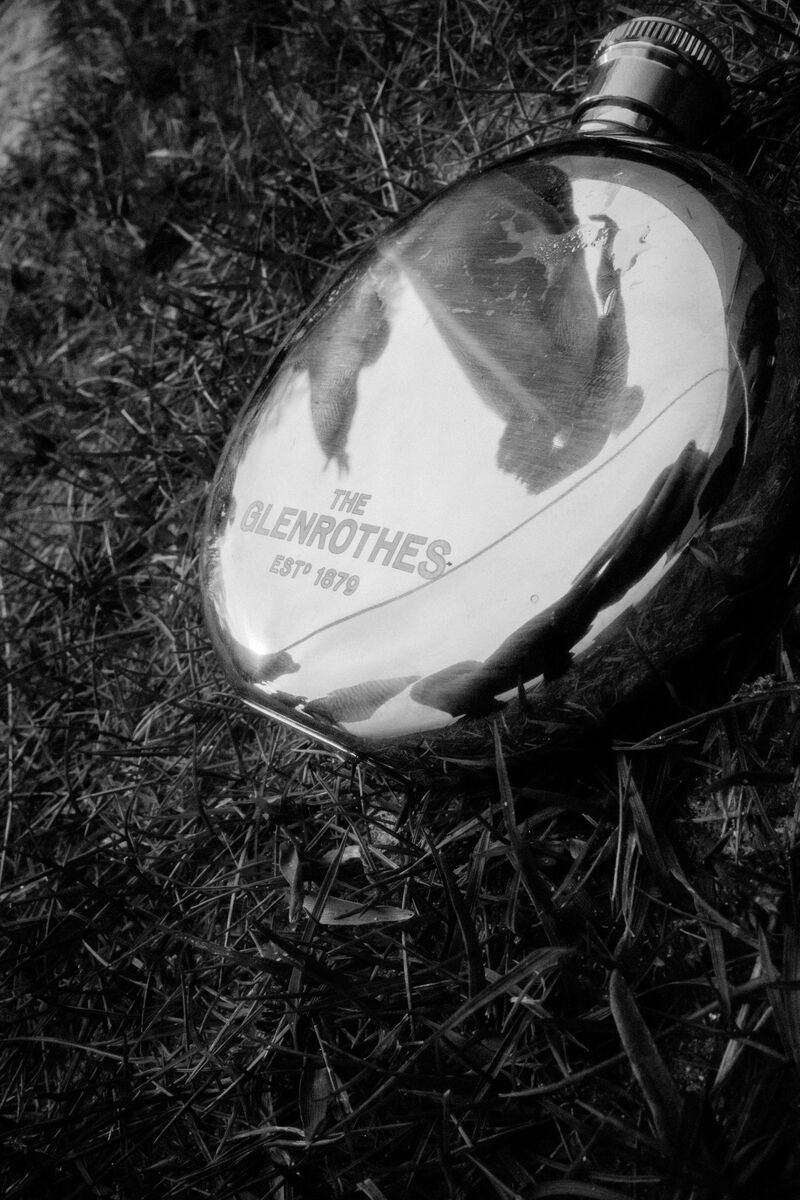

The second night’s dinner took the form of The Glenrothes x Ursula Salon in the Fife Arms Fog House and featured an intimate discussion with Randy Kennedy, design guru Sarah Douglas and Anna Lisa Stone of The Glenrothes about the role of destruction in the creative life of the 20th and 21st centuries, on the occasion of The 51, a rare Glenrothes single-malt release contained within a Jesmonite column that the owner is asked to crack open with a hammer to access the bottle. The column’s fragments can then be returned to The Glenrothes for re-assembly by a master of the Japanese mending technique known as kintsugi, yielding a new vessel that serves as a memento.

Ekow Eshun

Charlotte Jansen

Dame Sonia Boyce and Neil Wenman

Anna Lisa Stone of The Glenrothes

Sarah Douglas

Tali Lennox, George Rouy and Sam Jacob

The Fife Arms

Day 3

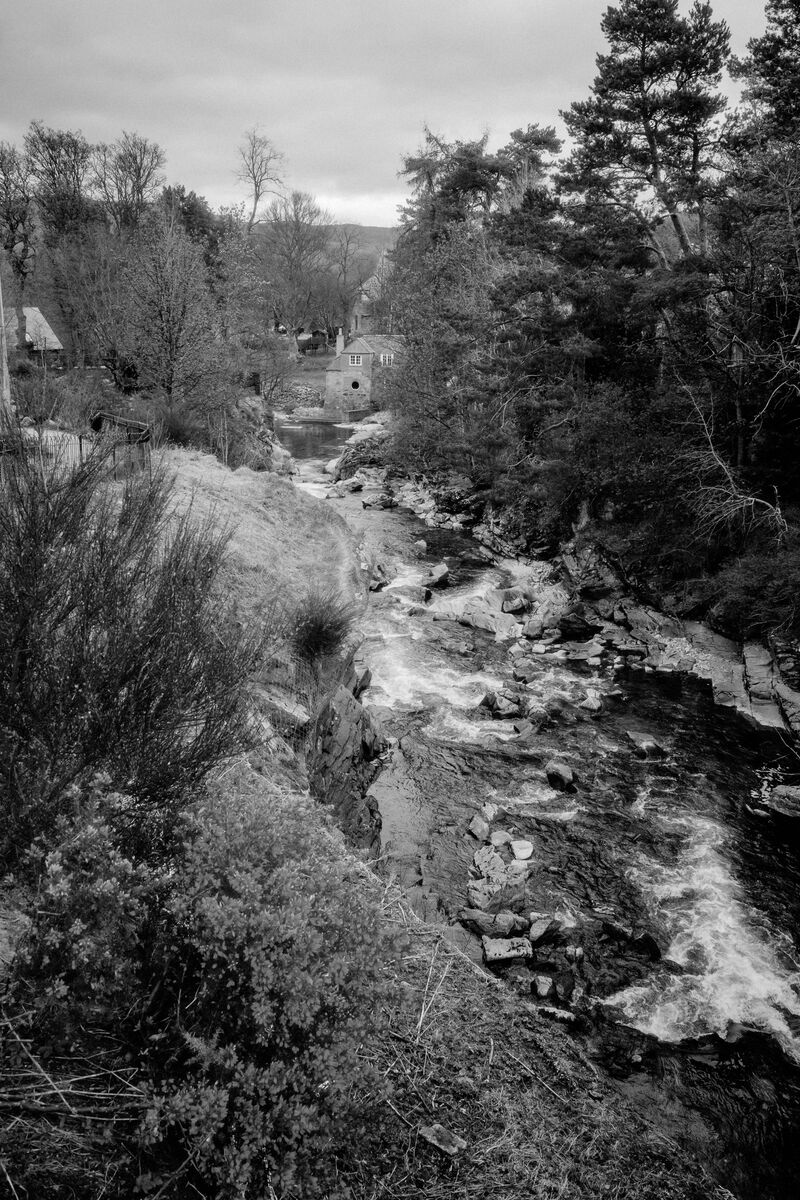

Sunday began early with an elective wild swim in the bracing currents of the River Dee, with The Glenrothes hip flasks and customized Dryrobes for intrepid swimmers as they exited the chilly waters. Later, back at the Village Hall, writer Charlotte Jansen and architect Sam Jacob concluded the Weekender’s conversations by taking the audience on an entertaining, erudite virtual tour of Cosmic House, the postmodern residential fantasia created by architect Charles Jencks (1939-2019). The house’s history is the subject of an essay by Jansen in the current issue of Ursula.

Jansen: “You encounter Jencks’s eccentric philosophy at the very beginning, when you enter the house. Actually, it starts even before you enter, because the house has two front-door handles, one that works and one that doesn’t. This is a thing that happens throughout the house. He’s constantly trying to wrong-foot you and make you think twice about what you’re doing and how your body is interacting with the space. Which is in some ways a kind of nightmare. I mean, it’s funny for a sec, but what if you had to live as a family in that kind of funhouse?”

Jacob: “The house is filled with columns that don’t support anything. It’s a classic postmodern-architecture joke: a column that doesn’t do the job a column is supposed to do. There are lots of different versions throughout Cosmic House. Sometimes they’re missing the top, sometimes they’re suspended off the floor. It’s maybe one of the reasons that people find this era of architecture so baffling and frustrating. Postmodernism begins as at least an attempt to destabilize power structures. But very quickly, even by the late ’70s, certainly by the early ’80s, it becomes the language of Thatcherism and Reaganism.

Sam Jacob and Marco Capaldo in the River Dee

After the wild swim

Sam Jacob and Charlotte Jansen

–

With thanks to The Fife Arms, The Glenrothes, Dover Street Market, Farm Shop, Ruinart, Comme des Garçons Parfums, and Hauser & Wirth.