Films

What Pattern Can Do

Sonia Boyce on the magic of wallpaper

- 6 June 2025

- Issue 13

- This article was produced to accompany a short film, Sonia Boyce: Wallpaper (2025) directed by Yvonne Zhang.

- Related Artist

- Sonia Boyce

Born in London in 1962, Sonia Boyce became known within the British Black Arts Movement of the early 1980s for her pastel drawings and photo collages that spoke to issues of race and gender, among many others. In the 1990s, her interests became more collaborative and improvisational—transforming performance into documentation and documentation into material for art works. An ongoing theme in her career has been pattern, rooted in part in her mother’s profession as a dressmaker. Boyce is known for her subversion of the traditional role of wallpaper as a passive, decorative background, turning it into a surface for complex beauty, disorientation, polemic and historical exploration, much of which she leaves conceptually open-ended, available for interpretation by viewers. At the 2022 Venice Biennale, she presented “FEELING HER WAY,” a sumptuous multimedia exhibition that revolved around forgotten British female singers of African, Asian and Caribbean descent, and earned her the Golden Lion; this past year, she was awarded a damehood (DBE) for her outstanding contribution to arts and art education. For Ursula, she recently sat down in her studio to talk about her inspirations—as disparate as Warhol and Willy Wonka—and the subtle power of wallpaper. This is the seventh installment in our Material series, which examines artists’ transformation of raw materials.

Francis Till: We’re in your studio in Bermondsey, London, and we’re going to be talking about wallpaper, among many other things. When did these space-filling patterns first enter into your work?

Sonia Boyce: When I was a student, I would do these drawings in which I would be the central figure, but there would be no background. My life-drawing tutor would say, “Oh, you never put the figure in its context. The figure needs a context.” So I thought if I put pattern in the background, a wallpaper, maybe I’m starting to give it a context. I was thinking about my parents’ home in the ’70s, where pattern was everything. My mum was a dressmaker, so she would bring home bags of pieces of cloth, which we would play with quite a lot. Pattern was always in the background for me. In time, of course, I came to understand a bit about someone like William Morris and his use of wallpaper, as well as Warhol, who became a very important figure for me.

FT: Wallpaper is inextricably connected to the history of decorative arts and design and is more often associated with interior, private, domestic spaces than with institutional or public settings. As a visual artist, can you describe how you define your relationship with the idea of the “decorative?”

Sonia Boyce in her London studio, 2025. All photography: Lily Bertrand-Webb

“My parents’ home was completely covered. Every room had wallpaper, highly patterned. . . . at nighttime, I would imagine that the wallpaper was moving. I’ve always had the impression there was an otherworldly quality to wallpaper pattern.”—Sonia Boyce

SB: When I was a young student, I was involved in a lot of the debates around feminist art practice. One of the key things about the debate at that time—late ’70s, early ’80s—was how to preface, you could say, the decorative arts. Historically, women artists were encouraged to be involved in decorative rather than figurative or landscape painting. It’s now less this way and not so gender-specific, but at that time it was a question of how to champion an art form, or a way of working, that had been demoted somehow because of gender. I was very clear in the early days that my use of pattern was a feminist statement. But pattern is also something that’s just stayed with me, not so much in terms of making a feminist statement but in terms of asking questions about what repetition can do. One of my recent realizations is that, with patterning, I can use elements of virtually anything, even if the elements are chaotic or at odds. Once I start to turn things into a repeated pattern, they kind of take on a different character, with a message less didactic than that of my earlier use of pattern. I think of wallpaper as quietly doing a certain kind of job. You notice, but you don’t notice, because it’s meant to be in the background. It announces itself, but really very quietly.

FT: Some of your work with wallpaper is not so quiet. There seems to be a tension in terms of what is foreground and background, and the work experiments with narrative. Maybe we can stay in the ’80s for a moment—there’s a work on paper featuring wallpaper patterns and the piece is titled Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great (1986), in which different parts of the world are depicted. There’s Australia....

SB: Yes, Australasia and Africa and Asia. With that particular work, I was using two different wallpaper designs. I had checked out a book on the history of wallpapers—which I still have, dare I say, I never returned it!—and in the center is a wallpaper created essentially to commemorate colonialism, you could say. The fiftieth anniversary of Queen Victoria’s reign over the empire. I took that wallpaper and used elements from it, matching an image of Queen Victoria with images of roses from a William Morris wallpaper design. So basically there was a mash-up between these two, sitting in the background of these four panels. The last panel is a drawing of myself, looking out toward the audience. I was using wallpaper that many people would think of as quite innocuous, but I was trying to foreground a political narrative within those wallpapers in the context of my being, at that time, a very young Black female who was born and brought up in the U.K. I was trying to wrestle with that history and legacy through wallpaper.

FT: From your early, more representational works, to today, your more conceptual and interdisciplinary pieces, there has been an ongoing engagement with identity, the social body and social relations. With wallpaper specifically, how do you see this in connection to your social practice?

SB: My early wallpaper pieces were designed by other artists. Slowly, I realized I could make my own, and out of that, I could create environments. My use of wallpapers now is about the processes of bringing people together and documenting them and using that documentation. When I go to the realm of display, I want to create an atmosphere within a space for the work to sit in. So wallpaper has shifted from being a certain signal of a narrative to being more about creating an environment, using the documentation and stills from what may have occurred in a performance as the material to create my wallpaper designs. The environments are not trying to replicate the performances. I’m just taking the documentation and going on a journey with it. So I have a very different take, now, not only on the way I make work but also on its message. I’m trying to avoid the message, because I think there are all sorts of problems around the didactic approach. I’m much more interested in what these documents and traces of something can do themselves.

FT: On a formal level, artists often have to respond, or not respond, to exhibiting within traditional modernist white-cube spaces. I’m curious about how your projects have become visually and experientially immersive, how you expand subject matter to fill space.

SB: In the ’90s, I started to involve other people in the making of the work. I became quite interested in a social practice and at what point a social space ends. Does it end when the artwork is made, or does it continue when the audience encounters the work? Are people encountering the work or are they encountering themselves within an environment? This is what I’m trying to achieve. Looking is not innocent. Something happens unconsciously because of the various elements that have been put together.

“There’s a small book by Paul Klee called Pedagogical Sketchbook, in which . . . he says that drawing is just taking a line for a walk. I really love this idea that you can have something and just go on a journey with it.”

Braided Wallpaper, 2023; Head I (Skin) & Head II (Dread), 1995 (reprinted 2024). Installation view, “Sonia Boyce. An Awkward Relation,” Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK, 2024-25. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: Above Ground Studio

FT: What was it about Warhol that influenced your work?

SB: I suppose I have Warhol to thank for bringing wallpaper into the gallery space and making it something to be taken seriously. My first encounter with him, I was quite startled. His wallpapers are very bold. There was something subversive about the repeated pattern he brought into the gallery space. For me it opened up the idea that walls could be art, not just a backdrop for it. It was this idea of taking on a room, taking on the spatial dynamics. I loved that. I thought it was quite genius.

FT: It’s a completely different mindset.

SB: Yes, and there’s irreverence. It’s like, “Yeah, soup can, Coke can. We all know what this is, but then you have to think, ‘Why is it here?’ ” We still treat galleries as if they’re chapels. I love the humor of Warhol’s work. But he’s also testing us: What can be in this space? What can we think about when we’re in this space?

FT: Music is a material and field that also has strong presence in your work. For your Venice exhibition, “FEELING HER WAY,” you collaborated with five Black female musicians, filling the space of the British Pavilion with videos of their performances alongside wallpaper and sculptural elements. How did you create the wallpaper for that work?

SB: “FEELING HER WAY” was, for the most part, made at Abbey Road Studios. The wallpaper included images of the connective cables, the floor, the walls, the edges of things. I wanted a photographer to capture the space we were working in, the equipment the crew was using, the lights, all of the things that would make up the experience of that performance. And then I wanted to use those stills as elements within the repeated pattern. I know it’s kind of breaking the codes of filmmaking to see the camera shake, the boom, the wires. But I wanted that to be the nuts and bolts, you could say, of the wallpaper. It was about saying, “This is what happened. This is what made what you are experiencing.”

FT: With “FEELING HER WAY,” you’re talking about this breaking of the third wall, bringing the recording studio into the exhibition space. And this mixing of public and private spaces is something that’s maybe visible in your earlier works, in which there’s something intimate or personal that you bring into the space of art. I’m thinking about works like The Ticket Machine (1990) or your Hair Objects (1993) or the enlarged photographic prints of body parts you presented as billboards. Do you see these as a starting point for working with wallpaper?

SB: Yes, in those works the body is up close, but you don’t know the person. So there’s a kind of meeting of anonymity and intense intimacy. At that time, in the ’90s, there was a lot of discussion about performance documentation, a sense that you really had to be there. Some people see documentation as a dull facsimile of the actual encounter with something taking place, and that’s an idea I like to play with. I’m using these so-called relics of a performance to create something else, which is not a documentation of a performance. I’m not trying to capture the moment, but to take the material of that experience to another place. There’s a small book by Paul Klee called Pedagogical Sketchbook, which comes out of teaching drawing, and he says that drawing is just taking a line for a walk. I really love this idea that you can have something and just go on a journey with it. See where it goes. The performances that I augment, or the people that I bring together, go on a journey. Then I have the remnants of that, the material that I accumulated from that experience, to see what I can do with it, to travel with it.

FT: Looking at the different wallpapers you’ve created since your first, Clapping Wallpaper (1994), there’s a real range. Some work with collage or photographic processes and others are hand drawn or even text-based. Can you tell us a little bit about these different visual tools and the process you go through when creating the works?

SB: I’m always taking an image and thinking, “Oh, can this make a pattern?” Can I make a pattern out of text? I can’t do the mirroring that I might do of an image because then the text becomes unreadable. With each item, I’m trying to figure out how I can repeat it. And if I do repeat it, does something interesting happen? I haven’t developed a science about it. There’s a lot of trial and error.

FT: If we look more closely at wallpaper as a physical material, what processes does it undergo from conception through to reception by a viewer?

SB: There are two types of wallpaper material: vinyl, which has a sticky back that you press straight to the wall, and then actual paper wallpaper, which has a slightly thicker layer on the back that you paste onto the wall.

FT: The more traditional thick, pasted paper?

SB: Yes, so thick it almost feels as if it’s holding up the wall, to a certain extent. With vinyl, a laser print image is printed on a very thin material, and when it adheres to the wall, the imperfections of the wall are shown. With wallpaper, because it’s a thicker material, it covers the wall and makes the wall feel a bit smoother. We needed to use pasted wallpaper for the British Pavilion show to actually hide the quality of the walls. It’s an early 20th-century building and has been battered quite a lot. So when I’m looking at an install, I have to ask, “How good are the walls?”

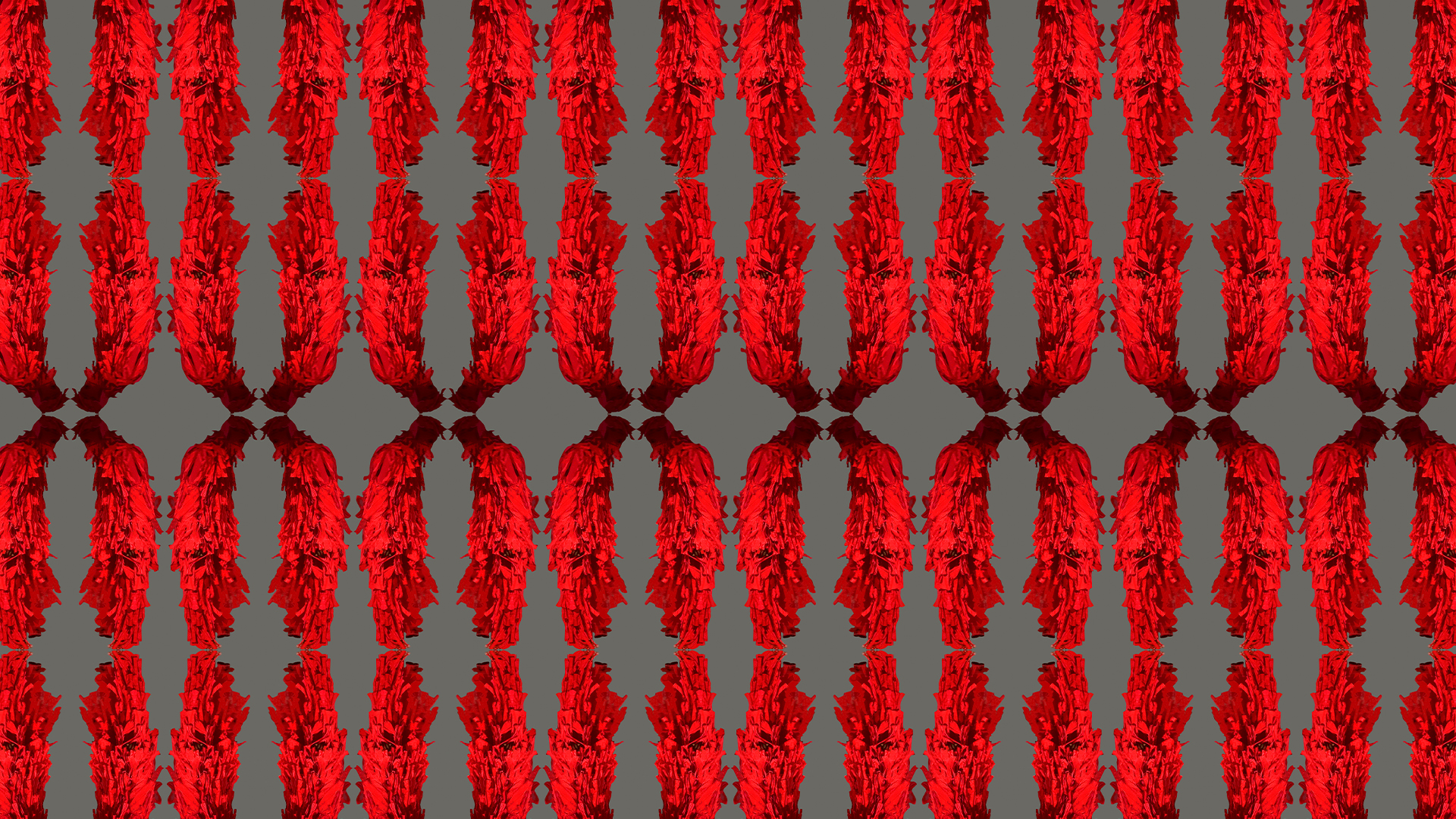

FT: Maybe we can talk a little bit about some specific wallpapers and connected projects, for example the Shaggy Bear pattern, which now forms part of your work Crop Over (2007)?

SB: Crop Over is the name of a carnival that happens in Barbados. There’s a lot of eating, drinking and dancing, particularly in the street. What interests me about Crop Over is that it’s a harvest festival that comes directly out of the experience of slavery. It celebrates when the last of the sugarcane at a plantation is cut. I have enormous love and intrigue for what I call “folk imagination” and for the people at festivals who dress up as animals or very exaggerated forms of things. In Barbados, Shaggy Bear is a quite regular sighting at social gatherings. The figure is dressed in red rags, and the performer inside the costume does a lot of acrobatic dancing and plays with the crowd. My mother is from Barbados. I grew up in London and had no idea about these folk characters. When I first encountered them, nobody else seemed to be paying attention. There’s something really disturbing and curious about this figure covered head to toe in red rags and doing these extraordinary movements. Later, I found out it’s actually symbolic of a West African deity called Orisha, a trickster figure. Using the stills from my film Crop Over, I created a wallpaper using the Shaggy Bear figure. It’s difficult to know what other people see when they see it—not only the figure in a singular sense, but the way I’ve made a repeat pattern of it.

FT: There seems to be a process of abstraction present through the repetition.

SB: Yes, it comes to look almost like a laurel leaf. I’m so used to the image now that I can’t see it the way other people might. Still, even to me, there’s something mysterious and unsettling about it. What is it? What is it doing? Why is it upside down as well as right-side up?

FT: Are you working on any new projects with wallpaper?

SB: Yes, I recently organized a silent disco and invited a lot of people to come and dance to two DJs playing for an evening. Now I’m working through the film stills for what elements from this evening could result in a wallpaper design.

“With each item, I’m trying to figure out how I can repeat it. And if I do repeat it, does something interesting happen? I haven’t developed a science about it. There’s a lot of trial and error.”

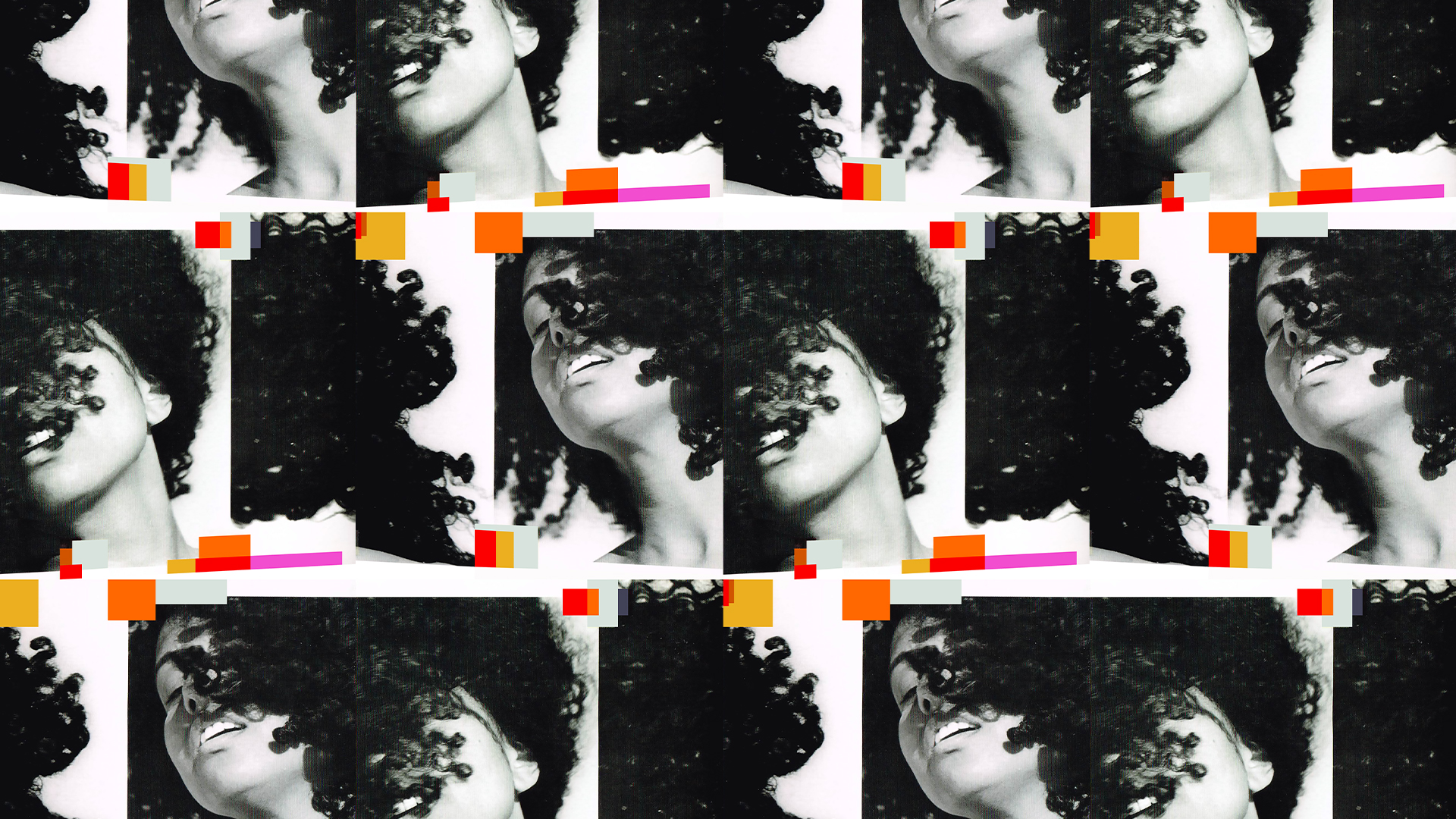

FT: This reminds me of your exhibition at ICA London. The connected wallpapers in that show featured dancers and had a choreographic element.

SB: The word choreography makes it sound as if there’s a plan, but for me, improvisation is key. And then tests and trials and taking the relics on a journey that comes from that improvisation. For the project at the ICA London, “We move in her way” (2017), I was very clearly making reference to the work of Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, whose work was about human relations and about people encountering each other through objects. I was also making reference to Dadaist Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s costumes and performance. I suppose a performance did take place, but it wasn’t an audience watching dancers. It was dancers encouraging audience members to be the artwork somehow, to be performers as well as themselves. And then from the stills, I had a kind of light-bulb moment, thinking, “Oh, there’s something really beautifully dramatic at play in turning those performance stills into a wallpaper design. So I covered lots of things, not only walls but also seated sculptures that people needed to decide if they were allowed to sit on.

FT: Improvisation and collaboration seem so central to what you do. When did you begin exploring the boundaries of authorship in this way?

SB: I was doing a project in the ’90s in which I wanted to film a set of twins, identical twins, performing. I hired a studio space, a producer, a camera and sound person, and I hired the twins. I would say to them “Would you do this?” And they would start doing what I asked them to do. And then they would go off and start doing something completely different. It became clear, if awkward, that I didn’t know how to direct. And they took advantage of this, you might say, because they were performers and were being filmed. We were there for a whole day. At a certain point, James Van Der Pool, the producer, said, “Is this what you want, SB?” And I was caught between what I was asking them to do, which was very simple and straightforward, and what they were doing, this side thing, which I did find interesting. They were very much playing around. I said, “Let’s just keep filming and see what happens.” A few years later, I was doing another project, and basically I was supposed to do a treatment, to write a script with camera directions, but by this point I thought, “No, I’m not going to be a director. I’m not going to look through the camera. I’m not going to listen to the sound. I’m not going to frame any of the images. I’m actually going to ask the crew to do what they find interesting and use that material.” I didn’t want to have control. I wanted to receive that material and work almost afresh. To get to know the material itself, as if it’s a completely independent entity. What is this stuff? How do I bring it together? What am I doing? Discovering that is the journey I love. Not knowing can be nerve-wracking but it’s also really liberating.

FT: This also feels connected to something you’ve said in previous interviews in relation to William Morris and how his patternmaking embraces the wildness of nature, bringing order to disorder.

SB: Yes, I think this is what pattern can do—hold a certain waywardness in imagery. It’s able to make it manageable, somehow. I keep thinking I must reread E. H. Gombrich’s book Art and Illusion. There’s something within pattern that is about trying to make order out of disorder. Morris does it brilliantly. I think these extremes are what I’m working between, more or less. Chaos and order.

FT: Earlier you mentioned patterns and textiles in your parents’ home. Is wallpaper also something you remember from your childhood years?

Installation view, “Sonia Boyce. FEELING HER WAY,” British Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy, 2022. Courtesy the artist and British Council. Photo: Cristiano Corte. Courtesy the artist and British Council

Sonia Boyce, Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great, 1986. Courtesy the Artist and Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

“There’s something so powerful about the idea of transforming one thing into something else . . . . I think this is the same illogical quality that operates within folk culture—a person suddenly becomes a tree or a horse or a Shaggy Bear.”

SB: My parents’ home was completely covered. Every room had wallpaper, highly patterned. It’s funny—I’m sure many children did this, but particularly at nighttime, I would imagine that the wallpaper was moving. I’ve always had the impression there was an otherworldly quality to wallpaper pattern. At night, the wallpaper was much more mysterious and unsettling.

FT: It seems to open a doorway into another field of perception or thinking?

SB: This is where things become tricky for me to find the words. I suppose one example was my recent exhibition “An Awkward Relation” at Whitechapel Gallery. I had the Braided Wallpaper (2023) and then fifty collages, a video and two images. What I wanted people entering that space to experience was how full the room was and yet also how empty, and to experience a vacillation between those two feelings. There’s so much that the eye has to do when looking at patterns or clashing colors. It has to work overtime to make sense: “What is this?” A pleasurable experience, hopefully, in part, but also a conundrum. This is where I am, having moved away from the works of the ’80s and ’90s, which conveyed a more singular message. I want people to find their own path rather than be told, “This is what you’re looking at, this is what it means.” There has to be a question mark somewhere. I do think when you go into a gallery or a museum you enter another realm, not separate from the rest of the world but at the same time a particular pocket of possibility. I’m addicted to that idea.

FT: About pattern, Gombrich proposed that such visual structures can give us a feeling of being told something. I guess what you’re saying is that we’re not being told something specific, a clear fact or a message?

SB: When I was child, I won a writing competition at school—the first thing I’d ever won—and my prize was a copy of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl. I read it to both of my kids when they were young. There’s a particular moment in that book where Willy Wonka is taking whoever’s remaining of the group into his experimental space. Wonka announces that there's a room filled with cubes that look round. Then there’s an illustration on the next page of blocks of cubes with eyes that “look ’round” the room when the door opens and the light comes in. On the walls of the same room is a wallpaper you can lick to have dinner. You can have a three-course dinner just by licking the walls. There’s something so powerful about the idea of transforming one thing into something else. As a six-year-old, I was completely confused. But I think this is the same illogical quality that operates within folk culture—a person suddenly becomes a tree or a horse or a Shaggy Bear. The illogical is magical. It’s like: How did that happen?

FT: Goodness knows we need a little more magic today.

SB: We really do. Reality is totally overrated at the moment.

–

Dame Sonia Boyce RA is an interdisciplinary artist exploring race, gender and cultural difference through film, drawing, sound and installation. A key figure in the British Black Arts Movement, Boyce was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation at the 59th Venice Biennale for her British Pavilion commission.

Francis Till is head of digital content at Hauser & Wirth.

–

Photography: Sonia Boyce in her London studio, 2025. Photo: Lily Bertrand-Webb

Artwork © Sonia Boyce, 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London

Wallpaper details: Sonia Boyce, Shaggy Bear Wallpaper, 2021; Sonia Boyce, We move in her way Pattern Audience, 2017; Sonia Boyce, Susheela, 2022. Wallpaper, dimensions variable