Essays

Through the Fire

Ross Simonini on personal loss and the immaterial function of art

Lake Avenue near the corner of Mariposa Street in Altadena, California, December 1971 © Leon Ricks Collection. Courtesy Altadena Historical Society. Photo: Leon Ricks.

I drove back to the fire at 9 p.m. Ninety-mile-per-hour winds whistled around the windows. Branches danced across the freeway. A ragged strip of cardboard flapped into my car’s undercarriage, dragged on for a mile and scuttled away.

This was my fifth disaster evacuation in California in a decade, and during each one I had fallen into a hypnotic survival state, numbly packing up a few items, usually forgetting something crucial. My life and property had never been seriously threatened, and I’d grown almost casual about the process. I’d developed a belief in immunity, the way children trust they will never die. I did not have the ability to believe in such a total, personal devastation.

Yet there I was, returning to the fire. If I was going to evacuate, even for a few days, I’d need my hard drives. But also, I should get them, just in case.

When I arrived at the house, I could see that the fire had spread: The entire mountain was now a streak of bright and terrifying light. It looked like hell seen from below.

The danger of the situation finally began to flicker in my nervous system, but I tried to look at the situation with cold logic: The fire was six miles away, farther than many other fires I’d known in the area, all of which had been extinguished quickly. This one hadn’t touched a home yet and the notion of it moving through thousands of structures to arrive at our house was just too absurd to consider at that point.

I packed my hard drives. Then I gazed across my studio and began considering what else I might grab. I could load up the car with everything.

My wife called: Our daughter was three months old, she reminded me, and I could not die out here. I pictured it: Struggling against the storm with one of my six-foot-tall paintings until it caught the wind like a sail and ripped apart in a final, fiery gale. Or: As I carried my final armful of art to the car, a chunk of rogue debris falling from the sky and cracking my head open. These were real, present threats I could understand, but I still could not believe that my home would burn. I took the hard drives and left.

• •

Four years before the fire, I’d begun an experiment to alter my beliefs through painting. I’d become exhausted with my worldview, which felt like a pair of cloudy glasses glued to my face. I needed change, and art had always been a useful tool for transformation. I expect paintings and songs and books to change me, even if not for the better. Art is not always self-improvement. There are risks. It can scare you and scar you forever. It can also heal and fortify and free you from your own restrictions. I have experienced all of these, sometimes from a single work.

Fundamentally, what I want from art is for another consciousness to permeate my own and show me a fresh view of reality. This is what keeps me from becoming stagnant. Life is movement, and art, when it connects, encourages the movement of life.

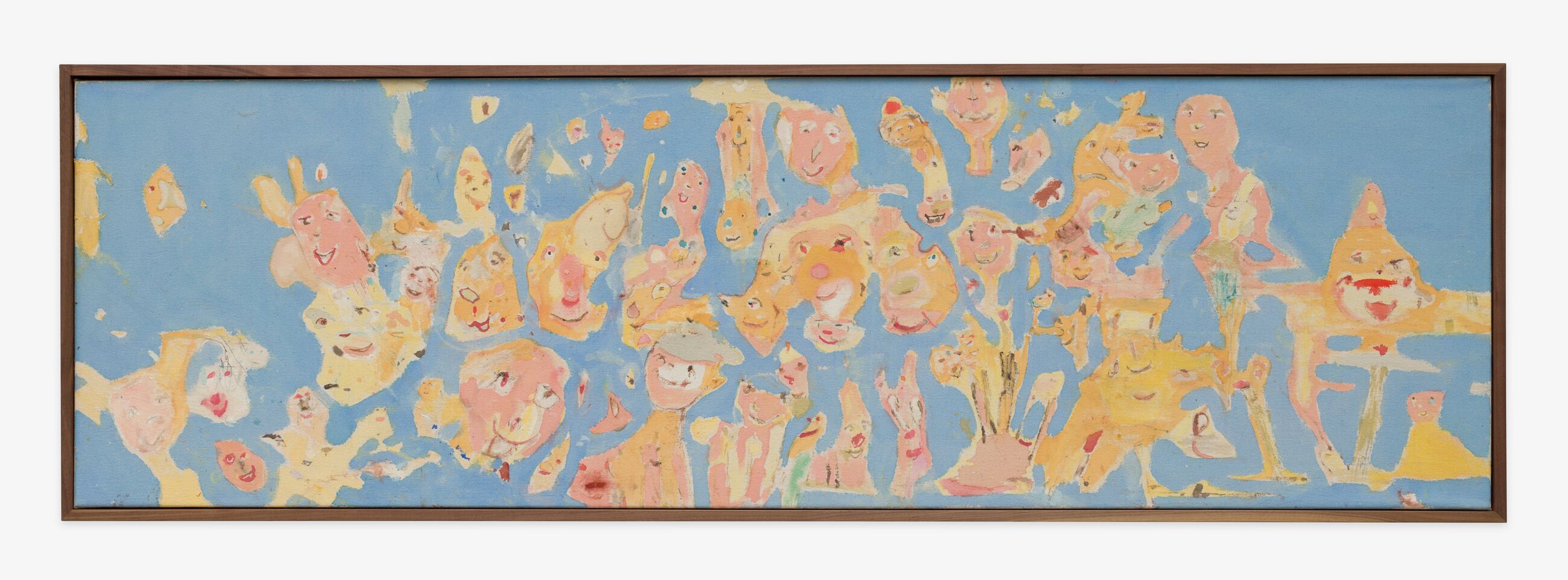

Ross Simonini, The Yets, 2023

“The loss of Altadena is a particular kind of grief. Rarely do we deal with the sudden and violent erasure of an entire place, a place filled with the vitality of every being who contributed to it.”

Since adolescence, I’ve enjoyed philosophies of negation—existentialism, nihilism, Zen Buddhism—and, over the years, some permutation of these became my attitude toward reality. For a while, this was useful, especially in a transitional kind of way. These -isms scrubbed away the film of neoliberal Catholic meritocracy that accumulated on my mind.

But eventually they eroded all my beliefs, and nothing remained: no self, no purpose, no god. I felt a dark hollow within me. I lost a sense of where to place meaning. Every ideology I came across became suspect, and yet, if I was honest with myself, I felt I still needed something. If I was being really honest, I needed something as potent as what religious people call faith–not a deity, exactly, but the kind of trust believers feel, the ability to know that I am being supported by the fabric of the universe.

Art had always been my best spiritual practice, so it seemed possible that making art could be a way of making a new belief. With this in mind, I began to consider how my own work could change me. If I was asking my paintings to transform viewers during brief encounters, what was the work doing to me over the weeks, months or years I spent staring into them?

So I began with a study of the smile. Smiles stimulate the kinds of mirror neurons and oxytocin dumps that people experience when they look at puppies and babies. The feeling is related to the Japanese concept of kawaii—a primal response to cuteness that fills the body with warmth—and to the effects of laughter, which even if forced can unleash joyful neurotransmitters. My idea was to weave together a tapestry of these joyful expressions—Levities, I called them—to create an image of what I wanted the world to feel like. What would it be like to stare at a patch of earth or sky and sense a reassuring presence looking back? If I could achieve this with enough intensity, even if for a moment, I hoped I could fundamentally alter my belief system. It’s like the old football adage: If you can touch the ball, you can catch it.

• •

In January 2025, my studio and home were destroyed by the Eaton Fire, which took hundreds of my works with it, including my five-year experiment in painting. Some of the individual paintings had sold already—one (The Yets) burned in a collector’s home—but most of them are now sprinkled in the soil, swirling in the wind, permeating the lungs of locals. This was the end of my experiment.

The feeling of this loss was not unlike a loss of life, in quality if not magnitude. There was, I believe, a life force in the things I lost. And, in a way, that had been the point of the experiment: to fill every work with enough energy to change me.

The loss of Altadena is a particular kind of grief. Rarely do we deal with the sudden and violent erasure of an entire place, a place filled with the vitality of every being who contributed to it. For more than half a century, Altadena has been shaped by artists (Paul McCarthy, Marjorie Cameron), including many Black artists (Octavia Butler, Charles White) who had been prohibited from settling elsewhere in the state because of racist redlining. The local reality we shared is now gone. Homes, parks and shops are in ruins.

Before this experience, I would not have described Los Angeles as a place known for its community. It’s a sprawling land of people sitting alone in cars, blazing individual paths. It’s famously difficult to meet people here, and one of Los Angeles’s secret pleasures is the satisfaction of a canceled plan. And yet, after this disaster, the amount of love and generosity I’ve received from this city is more than I’ve ever felt anywhere, at any time. I would echo this sentiment for the artworld, where the word community is rarely invoked without a cynical smirk. But at its best, the global artworld is a community of people who want to be changed by the power of objects.

Since the loss of our home, my family has received donations from everywhere. Internet acquaintances, total strangers, gallerists and companies I didn’t even know existed have sent money, art supplies, musical instruments, baby clothes, bedding, medicine. In the past, I bought the things in my life as any consumer would, with an impersonal click or swipe. Now all of the objects I own hum with a generosity, each of them reminders that kindness is always present, even in the most challenging moment of my life.

• •

Fire is transformation at the most elemental state. It turns nearly everything to smoke and ash, leaving behind only the immaterial. This fire has done the same to me. My life and my worldview have been leveled.

Naturally, destruction is also creation. Fire stimulates growth, releasing nutrients into the soil to prepare for new life. The goddess Kali kills the world with one hand and gives birth with the other. A friend once told me: “To make a great work, an artist must be willing to destroy the work at every moment of its creation.” Anyone who is successful must become intimate with failure.

For a long time, I believed my painting experiment had been a failure. After hundreds of hours of painting, my worldview had only been nudged. Occasionally, moments of true ecstatic feeling arose, but I was unable to sustain those states, even with constant, daily repetition. It was not until the fire destroyed the last physical remnants of the project that its objective could be fulfilled.

The philosopher George Bataille considered sacrifice as a pathway to mystical realization. He believed that when the mind is in survival mode, hoarding every bit of food, it remains earth-bound. But when we purposefully waste our resources we transcend the material and enter into an essential reality. In fact, Bataille organized an entire secret society to perform such sacrifices as a way to experience the divine pleasures that awaited.

Ross Simonini, The Ifs, 2023. Milk paint, egg tempera and graphite on muslin, 35 × 59 in. Photo: Leon Ricks. Courtesy Altadena Historical Society © Leon Ricks Collection

He knew that strong belief is generated both from within and without. You can pray for faith every night, alone in your bedroom, but being present at a communal ritual, collaborating with the people who share your belief, will make faith more vivid, more real. Religion is, fundamentally, community.

At the beginning of my experiment, this was not a thought I took into consideration. I enjoyed the art community, went to events, started an exhibition space, and like many artists, wanted to find my people. But I had not yet connected this desire with my project.

While a controlled experiment may be useful in science, I have no interest in an artwork that can be fully controlled. My experiment exploded, and what I tried to contain has now transposed itself to every thing around me. As I write this, the clothes I’m wearing, the room I’m sitting in, everything I have, was offered up by a world that wants to support me. It is as though the fire physically cast my paintings out into the world, freeing the feelings of levity I had ritually imbued in them. Like Frankenstein’s creation, my experiment was alive.

• •

In the months after the fire, I replayed the moments of the evacuation many times. Lying in bed, I would lose myself in my memory.

My muscles tensed in concentration as I retraced every choice I made on the night of January 7th. In my mind, I carried out family photos, instruments, art and everything that could never be replaced. Such dreaming became a nightly compulsion, as if I could change the past through imagination alone.

For a while it felt like self-torture, but I’ve come to think of it as just another experiment. In my nervous system, I have lived dozens of forking realities in which I save all the things that meant something to me. Even as a fiction, it has been physically relieving, a balm for my grief.

In the days after the fires, people often asked me how I was feeling, and mostly what I said was: “I can’t believe it’s real.” Today, both the future and the past seem more unreal than ever. The ongoing transformation of the planet is no longer a series of numbers and facts but a felt sensation, pulsing inside me. It’s a feeling that could turn a person bitter. But I don’t think this will be my fate, because I now believe I am living in a world that wants me to be here, and when I open my eyes in the morning, I am relieved to find it is still turning.

–

Ross Simonini is an artist, essayist, novelist, composer and multi-instrumentalist. He ran the art and music space Alicia on his property in Altadena. Exhibitions of his work have been held at François Ghebaly and anonymous gallery in New York and at Shrine in Los Angeles. His novel The Book of Formation (2017) is currently being adapted into a feature film.

–

Ursula Issue 13 includes a special section about the environment, as considered by a diverse group of artists, writers and activists. The section takes readers to Puerto Rico, where Daniel Lind-Ramos’s work is rooted in the Caribbean mangrove ecosystem and the dangers threatening it; to Los Angeles, where Charles Gaines has long fused conceptual sculpture and information conveying the speed at which environmental damage is occurring; around the world to see the imagery of the international movement known as Solarpunk, which promotes the power of hopeful imagination in the face of increasing climate threats; and to New York’s Healthy Materials Lab, a design research lab at Parsons School of Design radically retooling the spaces in which we live and work. The section ends with a moving essay by the artist Ross Simonini, a longtime resident of Altadena, Calif., who lost his home and his neighborhood in the recent Los Angeles wildfires.