Conversations

Storytelling

Imaginative hope and the solarpunk movement

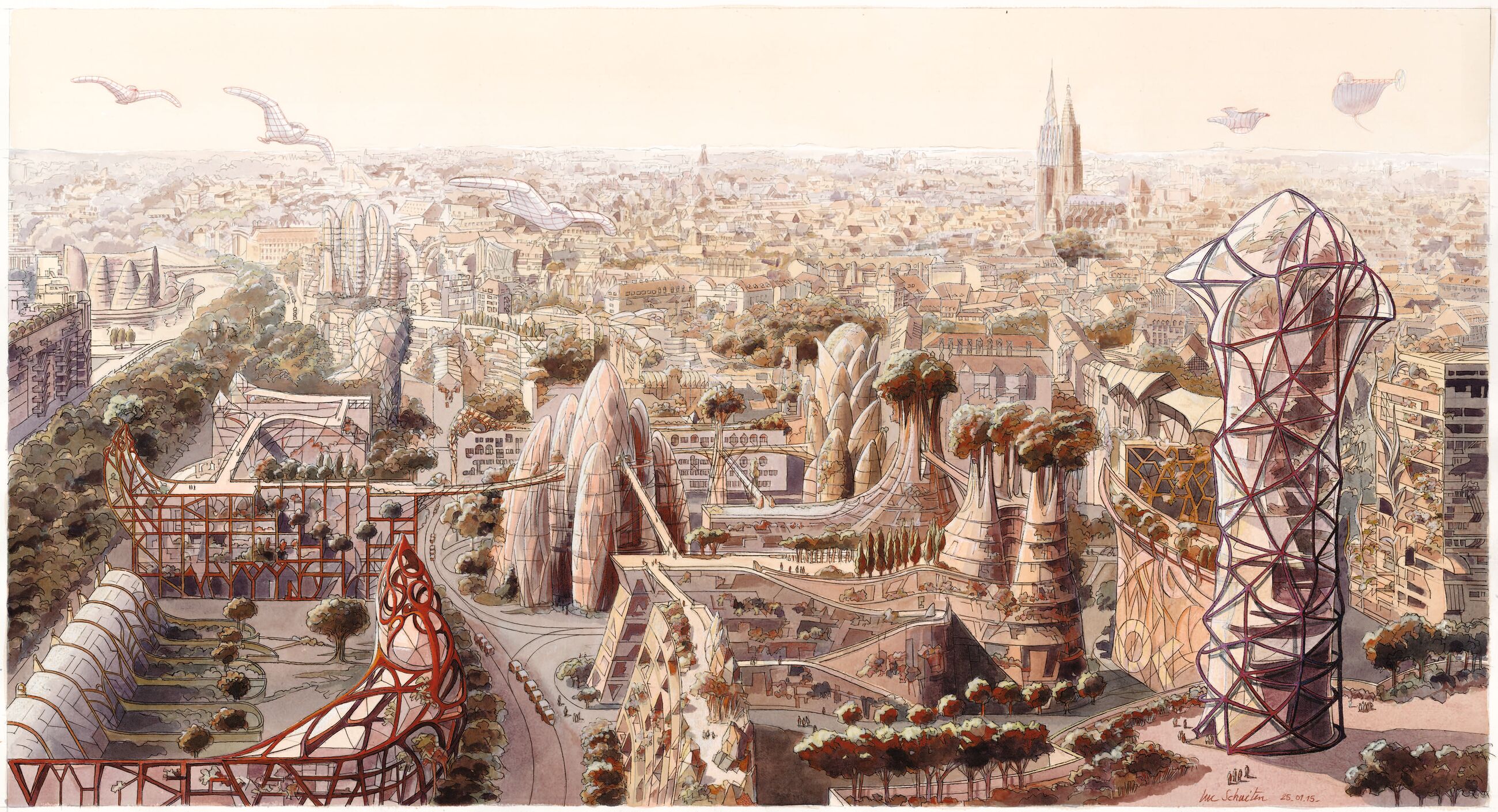

Grand panorama of Strasbourg in year 2100, offprint for exhibition at Shadok, Strasbourg, France, 2015. All illustrations: Luc Schuiten

A conversation with YouTuber Andrew Sage and hacktivist John Threat about the hopeful ideology behind the solarpunk movement.

Cliodhna Murphy: I’ve been curious about solarpunk as a concept, because it seems like a powerful counter for the kind of mundanity that ecocide has become, the damaged planet that is just part of our everyday lives. I wanted to set up this conversation with the two of you—who are in very different parts of the world, L.A. and Trinidad—to discuss some ideas through the lens of solarpunk, a concept for a different kind of world, one that has a more symbiotic partnership with nature. From your view, what is solarpunk?

John Threat: For me, the movement is about using the imagination. We live in a world where we’re indoctrinated into certain systems and it can be hard to think our way out of them. Around capitalism, for example. People say, “Well, what else is there?” or they point to what they think of as information, which is really just decades-long campaigns against the discussion of anything related to socialism or to any flexibility within existing ideas. A lot of young people are realizing that the world we live in came from visualizing dystopias. So one thing about solarpunk is the idea that we can reimagine.

Andrew Sage: I discovered solarpunk on Tumblr as an aesthetic and a literary genre, but it’s definitely evolved into a movement. It can be taken in a lot of different directions, but I want it to be taken in a productive, practical direction—for it to help shape the conversation about humanity, nature and technology, and about how these can exist in harmony, because we obviously don't have the answers yet. An important component of solarpunk is looking beyond the individual to the community.

JT: American media is a main driver of the idea that a superhero is going to come in and save the day, but community is the new “hero” in a lot of ways, especially post-pandemic.

AS: There's definitely an undercurrent and understanding of history that is based on individualism, a “great man” theory of the world and how things take place. But if you look at the peoples’ history, the history of the masses, of movements that have actually shaped things, which are not necessarily credited, it isn’t individual people who change the world. It’s networks of people working together.

Another aspect of this is understanding that renewable energy alone is not going to take the place of fossil fuels. In addition to the shift away from fossil fuels, there would have to be a controlled descent in our energy consumption. But I think we have an opportunity now, before things get to that point, to seek out ways to develop our energy autonomy, and I don't see that being guided by corporations or the state. Governments are not very comfortable with the idea of people not having energy bills to pay.

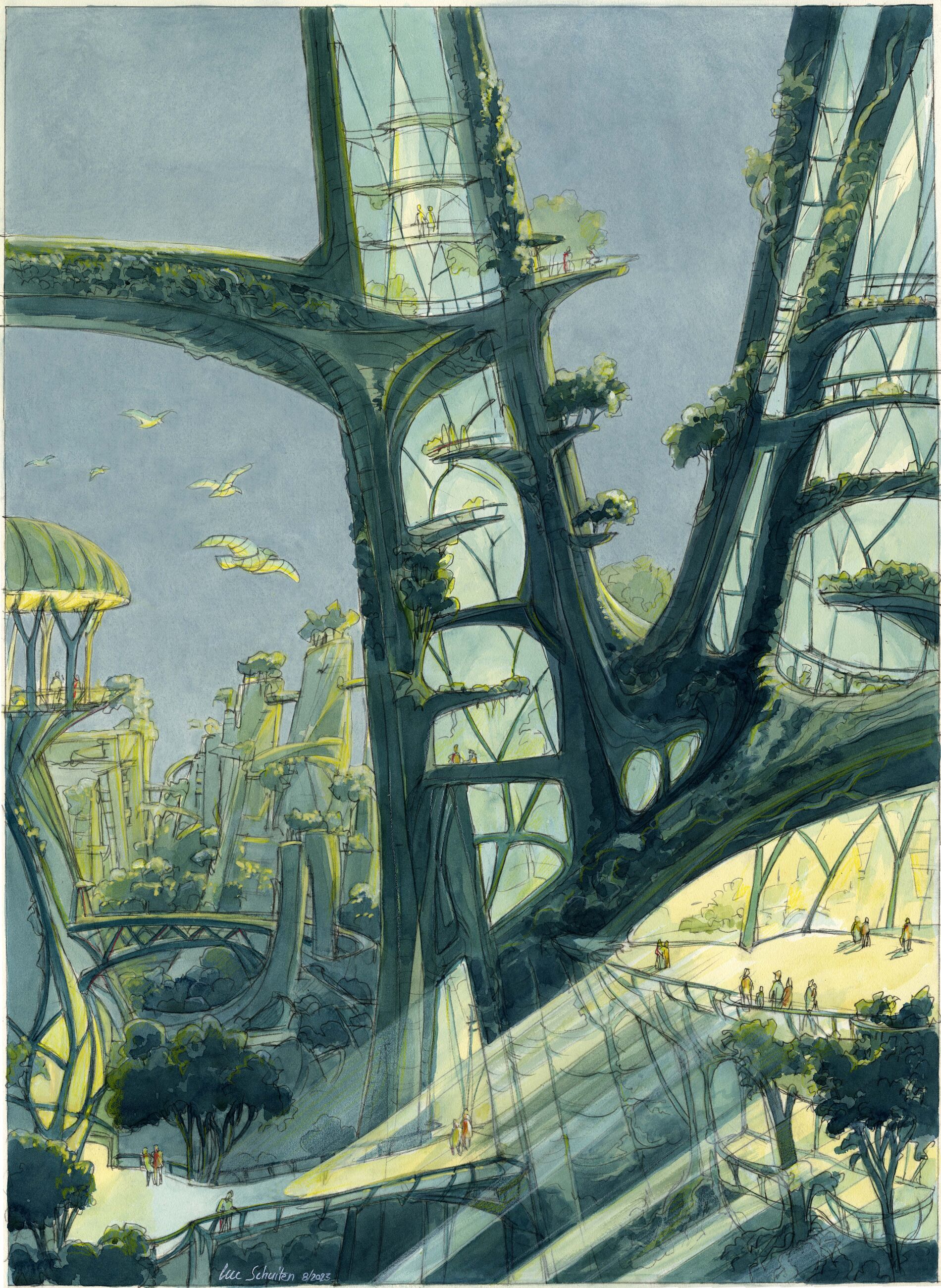

Poster for solarpunk exhibition, Atrium57, Gembloux, Belgium, 2024. Illustration: Luc Schuiten

“If I could get even ten percent of the population involved with any sort of experimental, nonhierarchical, imagination- and autonomy-focused approach to education, I think the effects would be almost instantaneous.”—Andrew Sage

JT: I agree with you about our energy consumption needing to change. There’s a Greek term, eudaimonia, which is a feeling of satisfaction from the things that we do to exist and persist. For example, I like to wash my clothes by hand. There's something gratifying about it. I take the time to wash and dry the clothes and it feels good. I'm not thinking, “I'm saving electricity and water.” It just actually feels good, the act itself. In a lot of ways, we've become disconnected from feelings like that. If there's more power left over, we’ll think up ways to use it. In our culture, we don’t say, “Hey, we could sustain ourselves.” It’s, “How can we burn it up?”

AS: Because we keep accelerating.

JT: Exactly.

AS: We've gotten more and more productive, but people are not working less. Eventually we're going to crash in some way, and I would rather have a controlled landing than a spinning-out on fumes. We need to slow down and have autonomy when it comes to our energy and water use and our food production. I'm not saying that everybody should be a farmer but that it would be a good idea to have a direct connection with the people growing our food, instead of consuming food grown halfway around the world. Things like that would help us develop an awareness of what daily life takes from the environment, and what we need to give back.

CM: Would you say that the idea of very local food production is solarpunk?

AS: I would say there's a very strong connection between the permaculture and solarpunk movements, because permaculture is not just about putting seeds in the ground and growing them. It's about considering the systems and relationships between living things and how we can facilitate those relationships with things like food forestry or successive planting.

JT: It’s interesting that people are wanting to grow herbs, even in urban environments. I see that idea propagate on social media. There's a whole style of making recipes super alluring, but part of that now is influencers who are growing herbs on the shelves where they live. That's the kind of thing I would love to see on a bigger scale. In my work, I try to think of ways to inject these thoughts we're discussing into the zeitgeist, where they can become super accessible to everyone, whether through localized skill-share or hacktivism. Andrew, I know you said you got into this initially through aesthetics, but is there a part of it now that you particularly enjoy?

AS: There was a time when I was really interested in permaculture, but more recently I’ve been developing a tech-critical approach, because I've noticed it's very easy to get enraptured by the aesthetics of solarpunk and forget the actual material impact on the environment. There’s a list originally developed by Jacques Ellul called “76 Reasonable Questions to Ask About Any Technology” that I’ve been exploring, thinking about which technologies we can maintain sustainably, which we'll need to adapt significantly and which we'll have to abandon for the sake of our future.

There’s a Greek term, eudaimonia, which is a feeling of satisfaction from the things that we do to exist and persist. For example, I like to wash my clothes by hand. There’s something gratifying about it … I’m not thinking, “I’m saving electricity and water.” It just actually feels good, the act itself.—John Threat

JT: It’s interesting to recontextualize the use of technology over time. We used to have a phone that you could connect to, and talk to people on. But the phone has evolved into a screen with video and apps that eat up massive amounts of your life, to the point where you live a different kind of life. I once ran into a cousin of mine and he said, “I went to the Grand Canyon with my family.” I said, “Oh, how was it?" And he said, “I didn't need to go, to be honest. It looked just like the pictures.” So you're literally standing at the majestic mouth of nature and creation, and you’re just like, “Eh?” I think there are a lot of people now who see nature only as a photo moment.

AS: It's a small thing, but I'm glad that there are phones that have time management features built in, because that has helped me tremendously. It's very, very easy to get lost, considering what we're up against. These tech conglomerates have spent years gathering data to refine their ability to capture and keep our attention.

CM: I've been reading about the idea of transformational sustainability in a corporate context. I guess the way that sustainability within organizations has been set up is for incremental change—bit by bit, we'll reduce our emissions, we'll increase the rate of our recycling or reduce the amount of waste that we generate in our supply chain. But it seems like that isn’t going to cut it. So what I've been reflecting on is: What would transformational sustainability look like in a corporate environment, in an environment in which people make money?

JT: That's a hard one. It can be hard to make transformational change if something doesn't seem to have a corporate value right now. A corporation might hire someone to do long-term thinking about sustainability, but they wouldn't want everyone in the company to be a long-term thinker, if that makes sense.

AS: Another reason people may not be able to think long-term is because they haven't been introduced to an alternative. That's where the storytelling value of solarpunk comes in, through various forms of media.

JT: Right, there is something about the mythology that comes from storytelling that resonates with us. That's really how we share information. When you give advice to someone, a lot of times it comes with a story illustrating how you came to that knowledge. Indigenous knowledge was quite often encoded within a mythology that people could memorize and see themselves in. In line with thinking up narratives and ideas to help the solarpunk ideology along, I would love to ask you, Andrew, what radical actions, if there were no restriction in terms of money or resources, do you think would push forward some of these ideas?

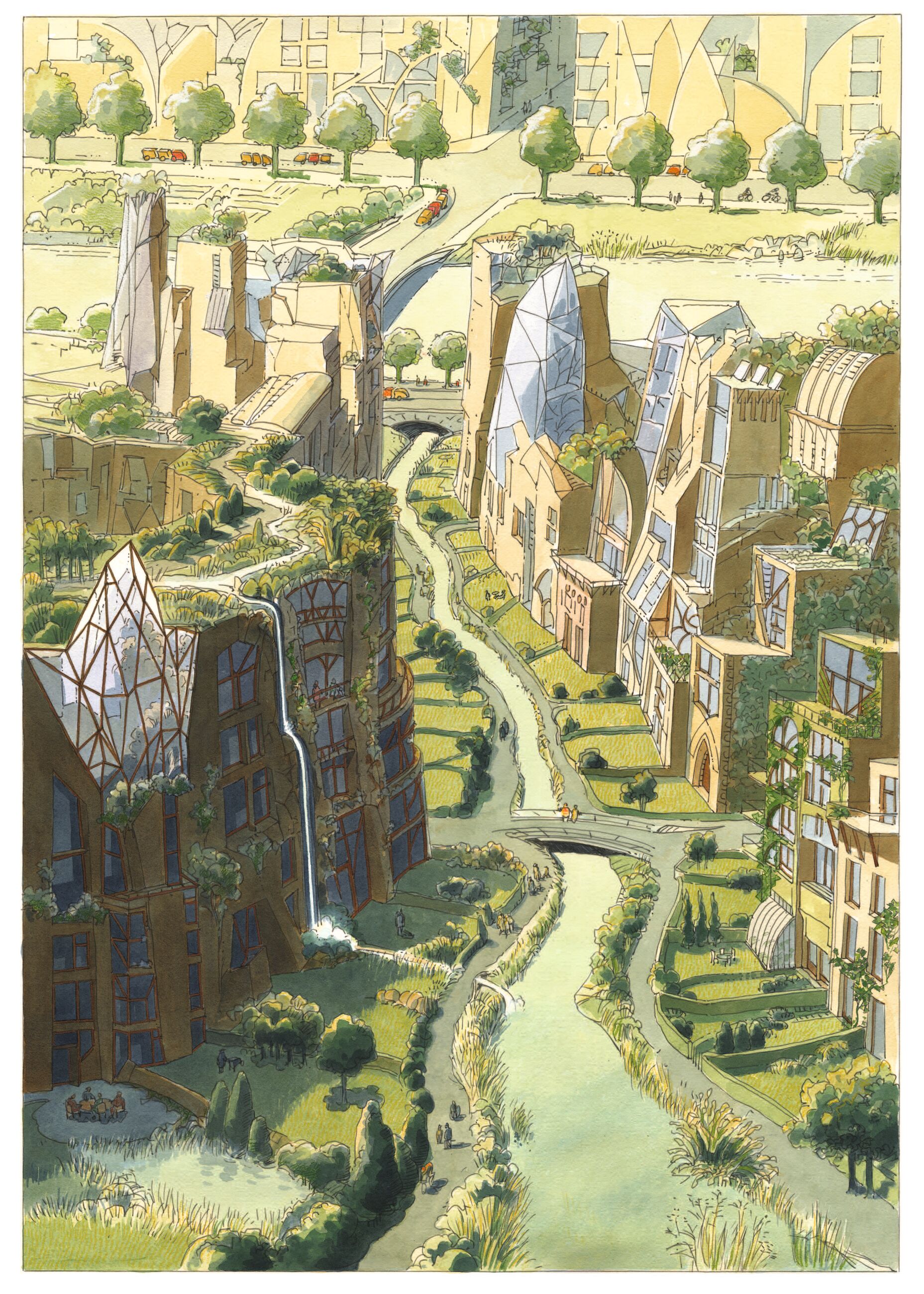

Poster for the exhibition “Water in the City,” Novatech Conference, Lyon, France, 2022. Illustration: Luc Schuiten

“A lot of young people now reject hopelessness and look at the world with hope. I call it sunshine nihilism. The future might be pointless or zero-sum, but in a way, that actually gives your actions more weight, because you have a chance to shape things.”—Threat

AS: I think part of what limits our imagination and our ability to change is the way the education system is set up. One of the most powerful actions of the early anarchist movements was the modern school movement by Francisco Ferrer, a Spanish anarchist who opened schools for adults to pursue a liberated education. Eventually he was killed by the Spanish government, and then the Spanish Civil War happened and Franco came to power. But prior to all of that, the modern school movement actually made a big splash. Everywhere from Latin America to Eastern Europe, people were experimenting with schools because change really starts with the young. If I could get even ten percent of the population involved in any sort of experimental, nonhierarchical, imagination- and autonomy-focused approach to education, I think the effects would be almost instantaneous.

CM: John, similarly, if you could make it all happen, what would it be for you?

JT: I love Andrew's answer, which I would also echo, about education. Learning how to think is more important than learning facts. When I was teaching activism, I had so many students with amazing digital skills, which they may not have even been aware they used every day. Using those skills could actually put pressure on culture to change, since so much of the power currently resides in the tech realm. I'm all for traditional modes of activism, like the protest in Germany against Tesla, but with access to so many digital tools across so many continents, you could really make amazing statements.

CM: You also taught a class about solarpunk, right?

JT: Yes, and I also taught about hacktivism and rebellion. The kids loved it. It comes back to what we were talking about before—how young people have grown up with the specter of nuclear war and the idea that there are no solutions. What I think is great is that a lot of young people now reject hopelessness and look at the world with hope. I call it sunshine nihilism. The future might be pointless or zero-sum, but in a way, that actually gives your actions more weight, because you have a chance to shape things.

AS: What’s great about solarpunk is that it can be applied to our current setting. It can be applied in some fictional cyberpunk dystopia. It can be applied ten, twenty years down the line. An early critique of solarpunk was that in its depictions in art, which are inspired by Indigenous aesthetics, nearly every piece depicted a temperate environment. So let's see some solarpunk deserts, some solarpunk tundras, some solarpunk scrublands and rainforests. I want to encourage people to not just take solarpunk for what it is, but for what it could be—a philosophy that can facilitate different permutations and adapt.

–

Andrew Sage is a writer, artist, organizer and YouTuber from Trinidad & Tobago. As an anarchist and a firm believer in “power to the people,” Sage is dedicated to invigorating imaginations and encouraging people to create a better world in the shell of the old.

John Threat is a hacker, futurist, artist, writer, director, solarpunk, professor and bike messenger. He has been featured on 60 Minutes and on the cover of Wired. John consults with futurist think tanks, dreams up radical art installations/interventions and co-founded Rip Space, an art/tech/media/hacker exhibition space in Los Angeles.

Cliodhna Murphy is Hauser & Wirth’s global head of environmental sustainability and is instrumental in developing and implementing the gallery’s climate action plan. She is also part of MOCA’s Environmental Council for Los Angeles and an adviser for the eco-arts organization Murmur. As well, she supports the Gallery Climate Coalition on a range of initiatives.

–

Ursula Issue 13 includes a special section about the environment, as considered by a diverse group of artists, writers and activists. The section takes readers to Puerto Rico, where Daniel Lind-Ramos’s work is rooted in the Caribbean mangrove ecosystem and the dangers threatening it; to Los Angeles, where Charles Gaines has long fused conceptual sculpture and information conveying the speed at which environmental damage is occurring; around the world to see the imagery of the international movement known as Solarpunk, which promotes the power of hopeful imagination in the face of increasing climate threats; and to New York’s Healthy Materials Lab, a design research lab at Parsons School of Design radically retooling the spaces in which we live and work. The section ends with a moving essay by the artist Ross Simonini, a longtime resident of Altadena, Calif., who lost his home and his neighborhood in the recent Los Angeles wildfires.