Diary

Abstract Expressions

Joan Mitchell remembers Harold Rosenberg (1906–1978)

By Laura Morris

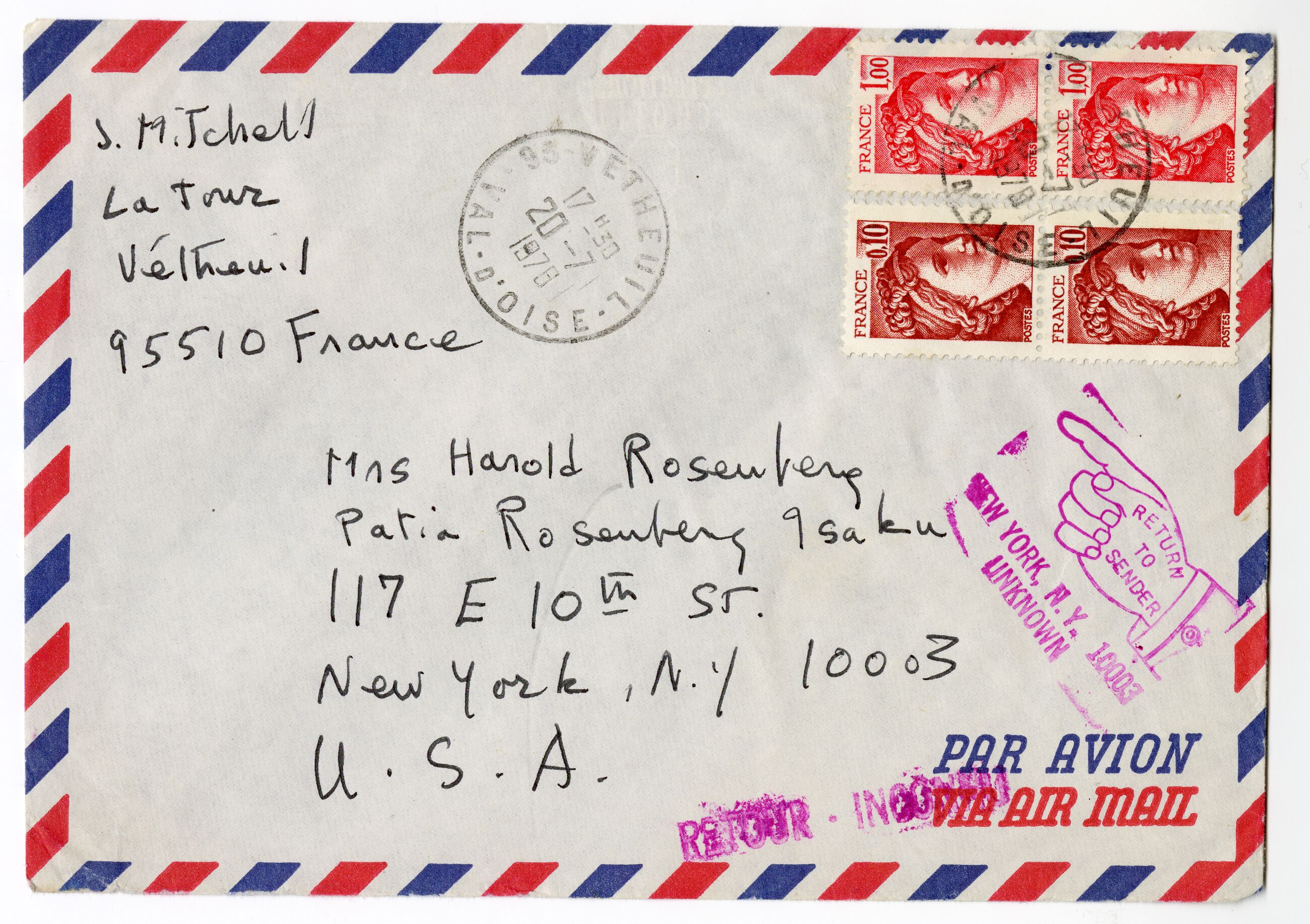

Undelivered letter envelope, Joan Mitchell to May Rosenberg and Patia Rosenberg Isaku, July 18, 1978. JMFA001: Correspondence. Courtesy Joan Mitchell Foundation Archives, New York © Estate of Joan Mitchell

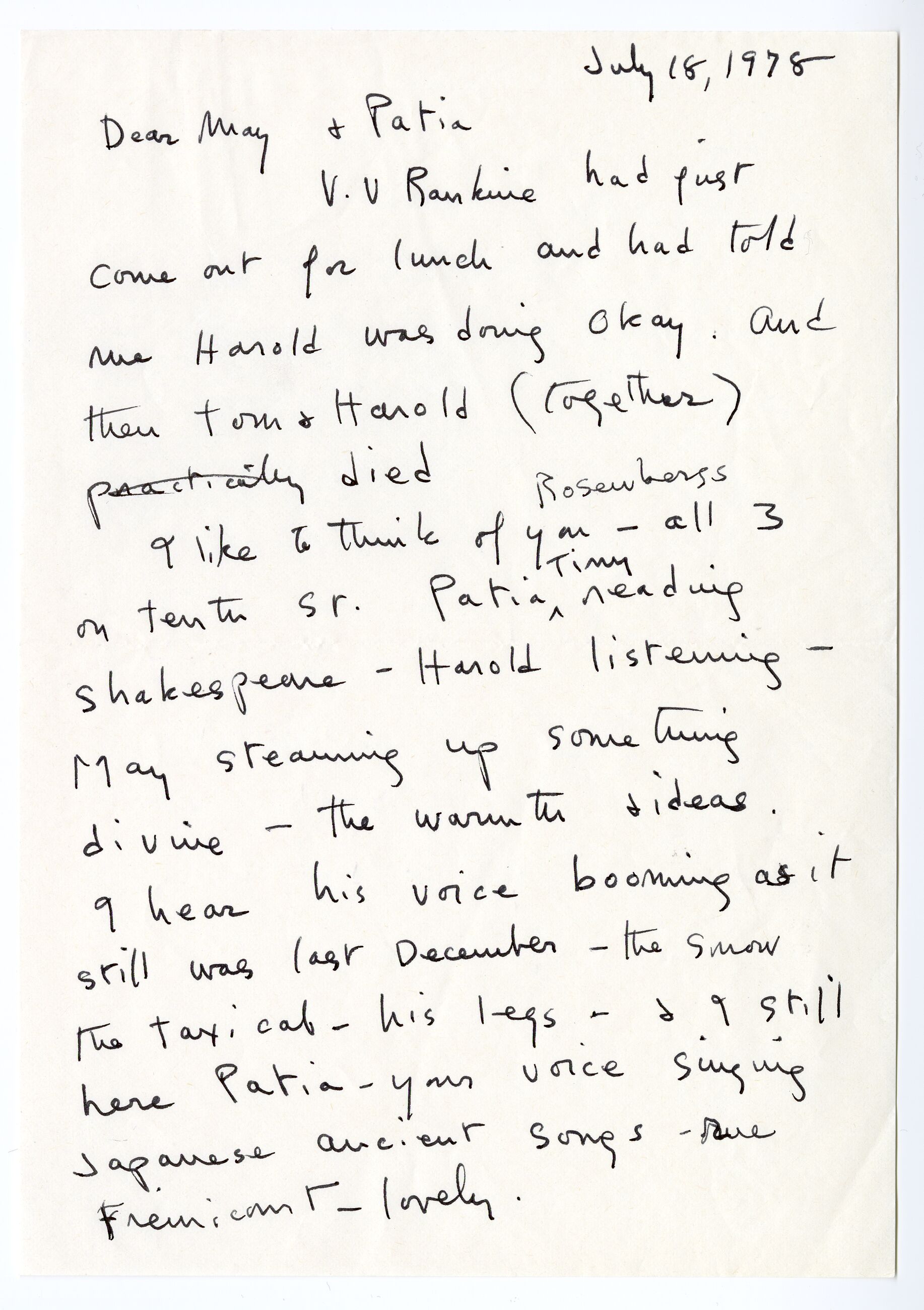

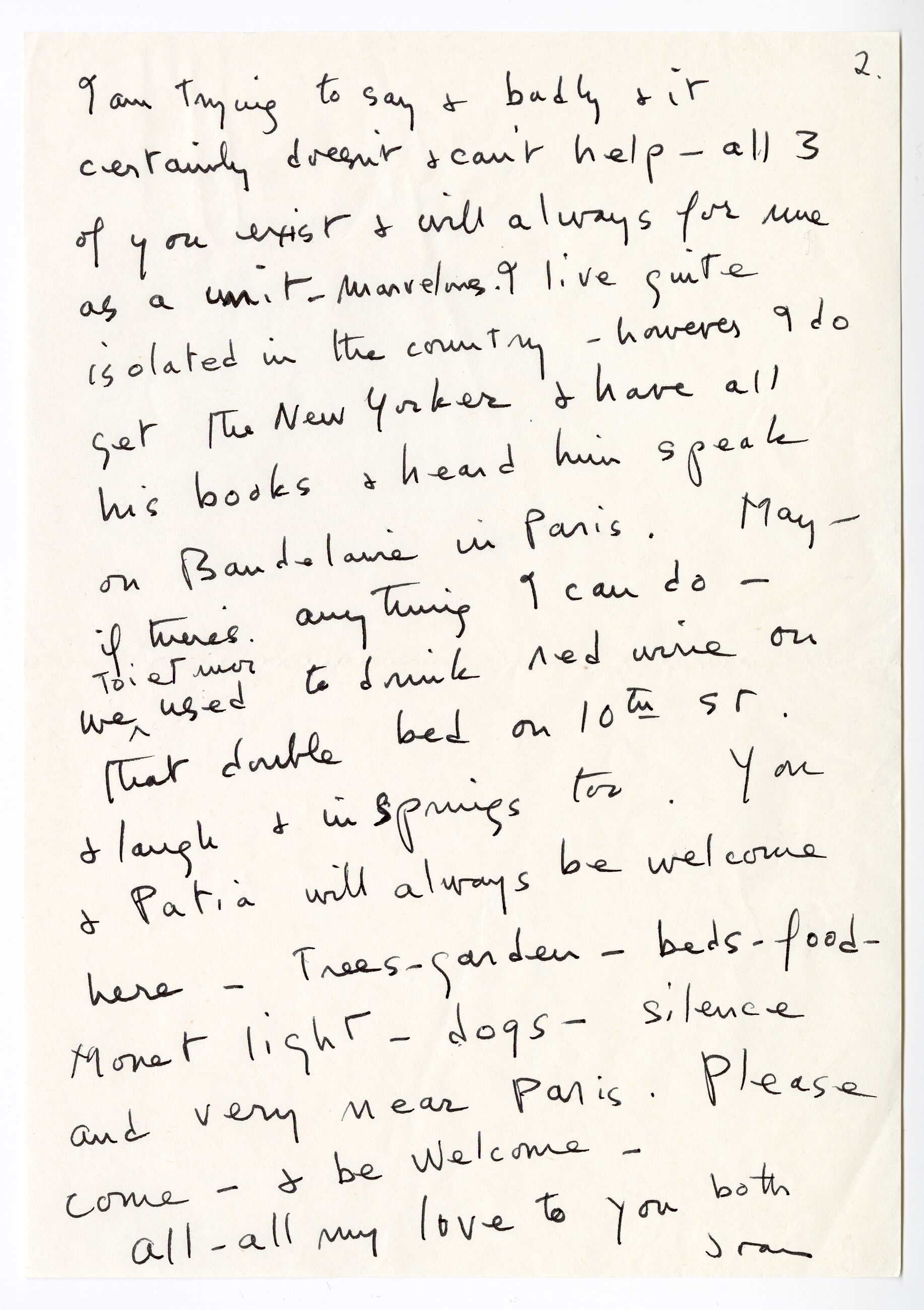

In July 1978, news of art critic Harold Rosenberg’s death reached Joan Mitchell at her home in Vétheuil, France, almost instantly. Mitchell (1925–1992), who had left New York nearly two decades earlier, was flooded with memories of time spent with Rosenberg and his family: drinking wine with his wife, May, on the double bed in the couple’s East 10th Street apartment; listening to their young daughter, Patia, read Shakespeare and sing Japanese folk songs; hearing Rosenberg, in his booming voice, hold forth on Baudelaire in Paris (likely at the 1968 conference held on Baudelaire’s centenary). Mitchell wrote a condolence letter filled with great tenderness to May and Patia, recalling “the warmth & ideas” that came with being in the Rosenbergs’ midst.

Rosenberg was a cultural giant known for championing American postwar painting during a kind of golden age of New York art criticism, propelled by dominant voices like those of Clement Greenberg, Leo Steinberg and Dore Ashton. Though it is not exactly known when Rosenberg and Mitchell first met, their paths regularly crossed from the early 1950s onward. Both were active participants in New York’s downtown art scene, spending evenings at gallery openings and artists’ hangouts like the Club and the Cedar Bar. They lived just minutes apart in Greenwich Village: Rosenberg at 117 East 10th Street, where he had been with his family since 1943, and Mitchell at 60 St. Marks Place, where she moved in 1952 after her divorce from publisher Barney Rosset. The art world was smaller then, and friendlier. In the summer of 1954, Mitchell and Rosenberg socialized in Springs, New York, even playing the occasional softball game with Franz Kline, Willem and Elaine de Kooning and other artists. Mitchell recalled years later: “Everybody was poor—not that that’s so heavenly—but everybody liked each other. If somebody sold a painting it was beers on the house and … people were very generous to each other, the artists.”

Undelivered letter, Joan Mitchell to May Rosenberg and Patia Rosenberg Isaku, July 18, 1978. JMFA001: Correspondence. Courtesy Joan Mitchell Foundation Archives, New York © Estate of Joan Mitchell

In 1961, Rosenberg’s landmark book The Tradition of the New was published in paperback by Grove Press under Rosset’s direction. Though Rosenberg referenced Mitchell in a few of his writings over the years, he wrote at length about her work only once, in a 1974 New Yorker review of her solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art (he had taken over that magazine’s weekly art column in 1967).

The two also shared ties to Chicago, specifically to Poetry magazine, where Mitchell’s mother, Marion Strobel, served as associate editor, working alongside founding editor Harriet Monroe (“Aunt Harriet” to the young Mitchell). Harold and May Rosenberg lived in Chicago for a period in the early 1930s, and Rosenberg introduced himself to Monroe, who would eventually publish three of his poems in the February 1933 issue of Poetry. (Years later, his ARTnews byline stated that he had been an “avant-garde poet” before turning to art criticism.) In 1966, Rosenberg returned to the city regularly as a part-time professor at the University of Chicago, where he continued to teach until his death. In 1979, the university’s Smart Museum organized a memorial exhibition in Rosenberg’s honor, which included Mitchell’s painting Atlantic Side (1960).

Joan Mitchell, Atlantic Side, 1960. Oil on canvas, 87 1/4 × 84 1/4 in. Private collection © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Mitchell’s daily environment and personal circumstances had changed dramatically since those early downtown days of wine and stories with the Rosenbergs. In 1968, she settled northwest of Paris in Vétheuil on a hillside property with an expansive view of the Seine and the surrounding countryside. By the time of Rosenberg’s death, she had become an internationally recognized artist and, as she grew older, she was increasingly generous in welcoming others to stay with her in Vétheuil. The property overlooked—as Mitchell particularly relished emphasizing—the cottage where Claude Monet had once lived. “In the morning, especially very early,” she said, “it’s violet.” It was this “Monet light,” and the comfort of the trees, garden, beds and food—not to mention the companionship of her beloved dogs—that Mitchell offered to May and Patia in their grief.

Harold Rosenberg (second from left) with artists Norman Bluhm, Grace Hartigan and other guests at Joan Mitchell’s 1957 solo exhibition at the Stable Gallery, New York. In the background is Mitchell’s painting The 14th of July (1956) © Photography collection, New York Public Library. Photo: Walt Silver

For mysterious reasons (the address on the envelope appears to be correct), the letter never reached them, and it was eventually returned to Mitchell. If she contacted them by phone, the exchange is now lost to history. Though Mitchell was known for a tough, acerbic public persona, her letter to May and Patia provides a telling glimpse of the deep affection, tenderness and care that she extended to those in her orbit and of her loyalty to longtime friends.

This year is Mitchell’s centenary, and her powerful abstract paintings will be specially celebrated around the world. On a much more intimate scale, this letter bears witness to her deeply lyrical and poetic way with words.

–

Laura Morris is the director of archives and research at the Joan Mitchell Foundation in New York, where she collaborates with scholars, curators, artists and students who are interested in Mitchell's life and work. Her book Joan Mitchell et ses chiens / Joan Mitchell and Her Dogs (Editions Norma) was published in France in May.