Conversations

A Long Way from Home

Aria Dean explores Weimar-era Berlin and Black aesthetics

Aria Dean, digital renderings for the performance work The Color Scheme, 2025. Courtesy the artist and Filip Kostic

In November 2025, Aria Dean will premiere The Color Scheme, a theatrical work inspired by a little-known 1923 encounter between philosopher Alain Locke and poet Claude McKay in Berlin’s Tiergarten, the city’s historic park and a site of imperial architecture and tumultuous political memory. The performance will combine live acting with real-time video capture and a virtual reconstruction of the park as it was in 1923. Two characters loosely based on the men—“the Philosopher” and “the Poet”—move through the Tiergarten, their conversation unfolding in a single act that bridges realism and speculation, history and projection.

Drawing on fragmentary records of the original meeting, including Locke’s letters and McKay’s autobiography, as well as historical and philosophical writing spanning centuries by figures such as Friedrich Schiller, Dziga Vertov and Iris Murdoch, Dean uses the moment to hinge political, aesthetic and personal contradictions.

Ahead of the performance’s debut, Dean sat down with Jeffrey C. Stewart—a Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer of Locke—and writer Simon Wu to revisit the personas of Locke and McKay, Black modernism and queerness in Berlin during the Weimar era.

Simon Wu: It’s great to be here to talk about this project. Aria, the piece begins with a real moment in history, but there’s a current resonance that runs through the whole scripted work. Could you give us an overview of the piece and how you arrived at these figures and this moment?

Aria Dean: Absolutely. It’s a play, but it’s also a film—something close to a teleplay. It takes place on a proscenium stage designed for frontal viewing, with three rear projection screens and two cameras capturing the action in front of the two screens stationed toward the front of the stage, and feeding the camera’s view to the larger back screen. We’re essentially making a film in real time, and every aspect of the performance is composed with the camera in mind. Before Covid, I’d started doing more theatrical performance—writing and directing some plays—because I was feeling frustrated with sculpture and the static nature of making exhibitions. I had developed an idea for a four-person play using a similar live video system for “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer, but when the pandemic hit, it had to become a one-person filmed performance instead. So live capture and broadcast have been around in my work for a while.

SW: I remember you describing that setup—how it’s staged live but constructed for the camera as though it were a traditional film.

AD: Exactly. I’m interested in exploiting the space between theater and film—and here, I’m structuring performance around the needs of the camera. The play takes place entirely in the Tiergarten, rendered in Unreal Engine, the 3D graphics tool, as it was in 1923. When I was in Berlin a few months ago, I scanned the surviving statues from the Siegesallee—a boulevard that was commissioned by Kaiser Wilhelm II, lined with monuments to Prussian rulers and various German historical figures. It was heavily damaged in World War II and erased by the Allied forces in the aftermath. Most of the statues are now housed in a museum, Zitadelle Spandau. In the play, the monuments are returned to their original locations but are shown in their current ruined state. That tension—between a perfect model and a ruin—is central.

Jeffrey C. Stewart: I like how you’ve situated them—not just in the past, but in this kind of projected space. There’s a dialogue between the historical moment and the future in how you’re reconstructing it through film.

SW: How did you first come across that meeting between Locke and McKay?

AD: The original spark came when I read something—maybe a footnote in Kwame Anthony Appiah’s 2014 book on W. E. B. Du Bois—that led me to an article about the “Black horror on the Rhine” and this encounter between Locke and McKay. I wasn’t doing work on either of them at the time, but I found McKay’s account of their meeting in his autobiography very funny and very weird. From there, I dove into the biographical material and started reading their letters and other primary sources. The dynamic between them felt so rich and so unresolved. And the topics they discussed—Blackness, monuments, aesthetic politics—felt frustratingly relevant. A hundred years later, and we’re still in it.

Aria Dean, digital renderings for the performance work The Color Scheme, 2025. Courtesy the artist and Filip Kostic

SW: Did you approach the research as a historian or more like a set designer?

AD: A bit of both. I pulled from the monuments themselves, of course, but also museum records and photos from different periods. There was a lot of cross-referencing—what existed in 1923, what survived, what was moved. I initially set out to make a perfect model of this place that doesn’t exist anymore, as it would have been at the time. However, it became more compelling to design it according to a different model of history, a Benjaminian model that doesn’t treat history as a causal, linear series of events to be faithfully restored; it gets inside of and uses the moment.

SW: One thing I keep coming back to is the sculptures—how the philosopher sees them as beautiful, and the poet sees them as regressive. What drew you to that disagreement?

AD: The monument and style part—Locke liking the monuments and expressing more conservative tastes, and McKay being dismissive—is definitely in the mix. But I’m also thinking about the monument as a form, as a structure, and about what it does in society. What is its use value? Not just in the context of European classical or neoclassical art, the relationship between art and the state, but also art’s use value in producing a collectivity, in this case a “nation.” The disagreement between Locke and McKay—and the fact that McKay is entering the conversation having recently attended the Fourth Comintern in Moscow, where another conversation about art and value and labor was surely happening—opened up something bigger for me: a question around what kind of structural transformations are required for life to become livable.

JCS: It’s interesting you say “use value,” because that goes right to the heart of Locke’s thinking. He drew a clear line between art that exists for its own sake and art that serves a purpose—uplift, education, social change. That’s exactly what McKay pushed back against. For him, the idea that art has to do something beyond being art was a kind of trap. And then there’s Locke’s own taste—he loved classical form, high style. He was a total elitist about what counted as good art. So you get this tension: He’s calling for collective progress, but his aesthetic ideals don’t always match the culture or politics that he wants to move forward.

AD: That’s what’s so rich and bitterly ironic about the conversation. They’re both trying to figure out not only what kind of art matters, but how to do art and politics, and they don’t understand the full scope of what’s about to hit Europe. For Locke, it’s: Germany has used these forms—the monuments—to convey the “nation’s” history and create a sense of grandiosity around it. He’s saying, “We have heroes. We have to get that energy around our own history. Let’s get our place in the lineup.” For McKay, or at least the character I’ve written around him, the question is more like: What structural transformations are actually needed? Cultural nationalism, Black nationalism—they don’t necessarily solve anything. They potentially adapt this Romantic nationalism to new identities that better camouflage the most nefarious parts of such ideological programs.

SW: And of course, we only have access to this meeting through writing that has been filtered through McKay’s autobiography, Locke’s letters, other archival fragments. Jeffrey, how did this encounter first surface in your own work?

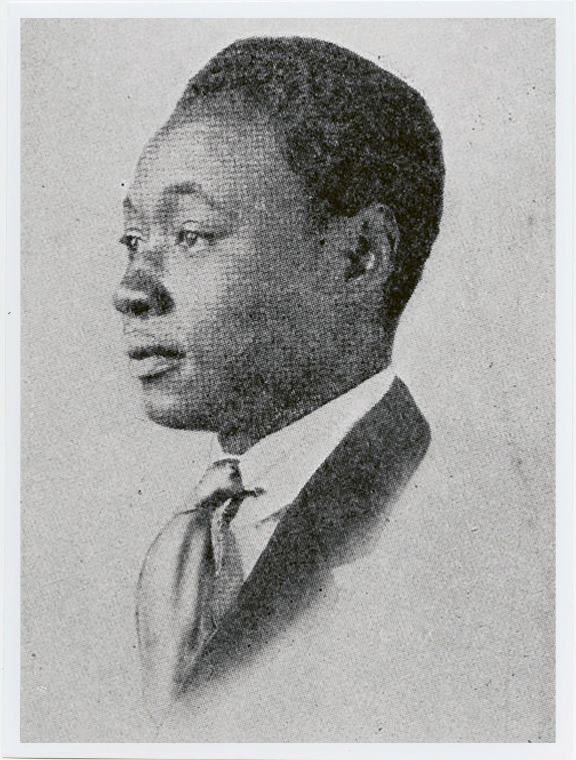

Claude McKay, ca. 1923

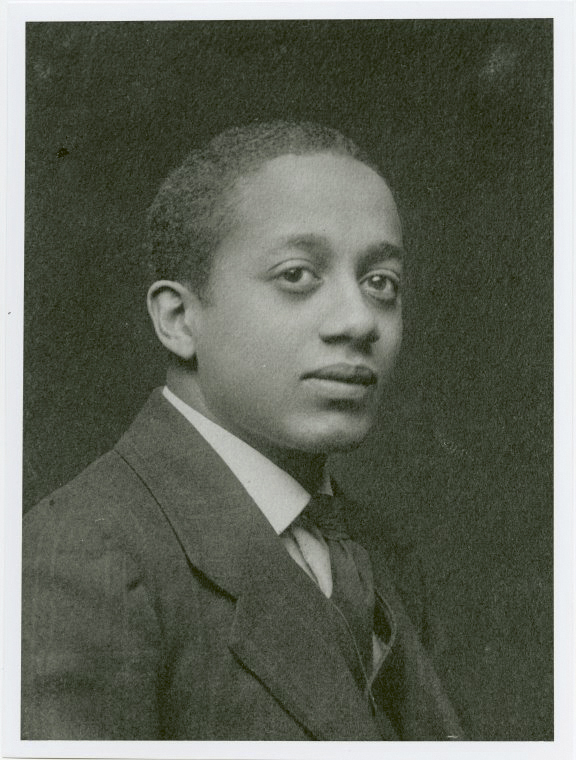

Alain Locke, ca. 1910s

JCS: I came across their meeting early in my research, but I didn’t focus on it much at first. Then I went to a conference in Wales, and the scholar Werner Sollors used the Locke–McKay encounter to completely trash Locke—like, look how conservative and out of touch he was. And I remember thinking, “Wait a minute.” When McKay’s autobiography came out, Locke responded with a scathing review—probably because he was angry about how McKay portrayed him. But he also raised a serious point: McKay’s critiques are sharp, but what does he offer in their place? What’s the bigger vision? McKay had criticized Locke for being too invested in institutions and racial uplift. But later in life, McKay converted to Catholicism—embracing a deeply structured belief system with its own hierarchy and traditions. And one of his best books, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, reads like pure Black nationalism. So Locke was really pointing out that McKay critiqued a system, yet ended up participating in it. And that was the real question for Locke: What are we actually doing here?

AD: Right, and that’s the knot at the center of the whole thing. Locke is very much someone who’s building for the future—he’s deliberate and strategic, using what’s available. And McKay is more improvisational, more present tense.

JCS: They’re both searching, both lost. And this meeting, in Berlin of all places, is a kind of existential collision. Locke is looking at Germany as a nation that came together quickly and used art to visualize collective identity. That fascinates him. Even though Germany had just lost a war, it had this ability to move forward using cultural forms.

AD: It’s absolutely existential. They’re arguing about art, modernism and how Blackness will be used and by whom into the future. But they’re also in a personal power struggle, one tinged with romance, professional rivalry and a sense of identification with one another.

SW: When it comes to writing their dialogue, how are you thinking about that?

AD: I’m not trying to re-create what was said. They were both so dynamic, or maybe mercurial in their thinking. I also wasn’t interested in heroizing them and calcifying their positions. That’s why I abstracted them, to build out a conversation that feels plausible but is ultimately invented. It’s fiction—based as much on their writing, their politics, their positions at the time as on other art history, philosophy and critical writing that I’ve read, from as recently as the 2020s. It’s a Frankenstein, a mélange.

SW: Something that is known is that Locke was in Berlin with his younger German lover, which probably couldn’t have happened in Washington, D.C.

A postcard showing Berlin’s Siegesallee, early 20th century

JCS: That’s right. Locke’s lover had taken him to the Tiergarten on an earlier visit. McKay had been shown around the city by the German artist George Grosz. Both men had already seen Berlin with someone else. Now they’re moving through the space together—unguided, on their own terms. At the time, Berlin had a strong and visible Black queer presence. It was even more open than Paris. Locke couldn’t have lived that way in Washington: He was teaching at Howard University, he had responsibilities and it was an extremely provincial city in the 1920s. In Berlin, he was able to be freer—at least temporarily.

As for their sexualities: McKay was probably more comfortably bisexual or queer and certainly had less angst around it than Locke. Locke, by contrast, was dealing with internal conflict. There’s a letter from McKay to Locke—one of the first I came across in the Howard archives—in which McKay says something like, “If you’re having this struggle with diffusion of emotion, maybe you should see a psychiatrist.” That’s a euphemism. He was basically saying, “You’re sleeping with too many people.” And when I found that letter, the archivists came rushing in and took it away. That’s how charged it still was!

AD: That’s amazing. It’s funny, because when I started writing this, I didn’t realize the Tiergarten was also a cruising site. But when I was in Berlin doing research, people kept pointing it out. Like, “Of course they met there.” The queer subtext I’d picked up on in McKay’s account of the exchange and in their letters just kept surfacing. And I think the flirtation was real—it’s embedded in their intellectual tension. In the play, I’ve written it almost like a romantic comedy or a first date. There’s a push and pull: curiosity, teasing, a little jousting. At one point, the Philosopher invites the Poet to go with him to his next destination—Cairo. And the Poet’s like, “Whoa, I’m not going with you.” That’s the only real liberty I took, and it was actually inspired by Locke’s interactions with Langston Hughes, with whom he was once in love. Locke made similar overtures. There’s a loneliness to him, a longing for connection that’s hard to satisfy when every relationship is a power negotiation.

JCS: That’s exactly it. Locke can’t just be with others, it appears. There was always something at stake. And McKay sees right through that. They were constantly circling each other—intellectually, politically—and in terms of their stature, they could even be called peers. But they kept undermining each other, whether by challenging each other’s ideas or unsettling each other’s sense of self.

AD: And that’s part of what makes them such perfect foils. They’re in different positions—one Jamaican, one American; one a poet, one an editor and philosopher; one open, one guarded.

JCS: That’s what makes it all so interesting. Locke is always absorbing. Even when he’s getting huffy and writing reviews, he’s taking something in. They both came away from that meeting changed, I think—even if they’d never admit it. They were waiting for something that never quite arrived. Like Waiting for Godot, but with monuments.

AD: Totally! And yet they keep returning to each other, in letters, in thought. They can’t really be friends because they’re each a horrible dark mirror for one another on so many levels. That dynamic was so generative to write. But it also made me want to open it up—to not call them by name and just let the conversation unfold.

–

Aria Dean’s The Color Scheme premieres at the Abrons Arts Center in New York as part of Performa Biennial 2025. The biennial—a three-week festival of live performance art—runs from November 1 to 23.

–

Aria Dean is an artist, writer and filmmaker based in New York City.

Jeffrey C. Stewart is a distinguished professor of Black studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the author of The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke (2018), which received the National Book Award for Nonfiction and the Pulitzer Prize for Biography. In 2024, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Simon Wu is a writer and artist. His debut book, Dancing on My Own, was published by Harper in 2024. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Bookforum and The Drift. He has two brothers, Nick and Duke, and loves the ocean.