Profiles

Going Somewhere Else

A weekend on the move with Henry Taylor

By Randy Kennedy

Henry Taylor. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Henry Taylor was zooming east on the Ventura Freeway towards Pasadena, his pressed white dress shirt half open and the windows of his rented Nissan Rogue rolled all the way down. A balmy afternoon windstorm was kicking up inside the car, drowning out the beat of Tony Allen’s ‘Ise Nla’ from the speakers.

‘Yeah, man—Wow!—you know what I mean?’ Taylor called out over the roar.

One of most admired Los Angeles artists of his generation, Taylor is given to unmoored expressions like this when he is in a good mood, conversational riffles more about sound than syntax, good for keeping silence at bay.

‘Woo, shit! Yeah, man! I mean… you know? You know?’ Oftentimes a listener, being asked if he knows, doesn’t quite know what it is that he’s supposed to know. But there’s never any doubt that Taylor does.

We were headed to the Rose Bowl Flea Market, the Los Angeles scrap-pickers’ valhalla, which had just turned half a century old, and on our way we were passing through or near some of the city’s most unassumingly consequential art-historical ground. Salvage yards not far from us had supplied the building blocks for the assemblage sculpture of John Outterbridge. The once-derelict storefronts of downtown Pasadena had provided studio space in the 1960s and 1970s for artists like Bruce Nauman, Richard Jackson, Paul McCarthy, Judy Chicago and Barbara T. Smith. The Pasadena Art Museum (later to be the Norton Simon) had hosted Duchamp’s first American retrospective in 1963. And a few years later the museum would give a teaching assistant’s position to a young artist named Senga Nengudi, who would draw pivotal inspiration from the performance-charged work of Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg.

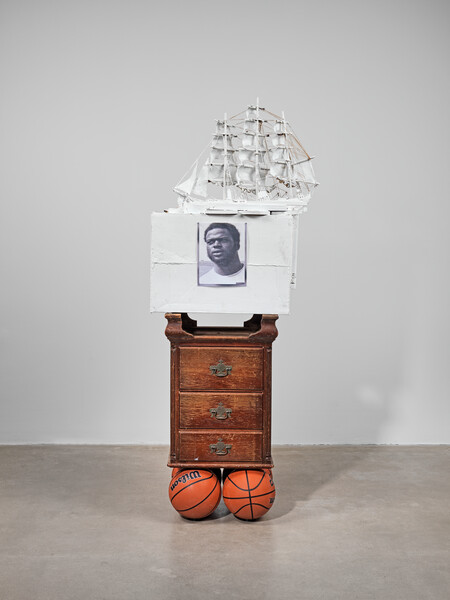

The flea market visit, one Saturday in early October, was proposed by Taylor less as a weekend lark than as a work trip, a chance for him to surf the stalls and blankets in search of feedstock for the assemblage sculpture that has begun to take up a larger portion of his time, studio space and mind.

‘I didn’t have any money and I’d look at a box, a cereal box … a cigarette pack, and I’d say, ‘Hey, hell, that’s a good enough canvas. Let me slap some gesso on that!’

Taylor, who recently turned 62, is known primarily as a painter, one who spent many years as a word-of-mouth sensation among his peers before finally gaining greater recognition well into his 40s. But since almost the beginning of his life as an artist he has also worked in what might be called utility sculpture, or maybe object-based painting, making pieces using practically anything at hand that serves his purposes, driven at first by economic necessity but more fundamentally by a churning, questing impatience with genre and form.

‘Early on, I didn’t have any money and I’d look at a box, a cereal box or some kind of little box, a cracker box, a cigarette pack, and I’d say, ‘Hey, hell, that’s a good enough canvas. Let me slap some gesso on that! Hot glue it to make it strong. I figured out that I could just put gesso on things and I didn’t have to spend money on anything but gesso.’

The cigarette boxes in particular became a kind of Taylor calling card throughout the greater Los Angeles area. Pocket-sized three-dimensional paintings—some elaborately worked, some gesturally spare, as close to abstraction as Taylor gets—they occasionally ended up as bartering chips in lieu of cash or as gifts to friends, much as John Chamberlain bestowed small crushed-cigarette-pack sculptures during his life.

‘I didn’t want to beg nobody and or owe nobody no money,’ says Taylor, who held a grab bag of jobs, and also worked for years as a psychiatric tech at a state hospital, before being able to support himself as an artist. ‘I was always willing to work. So I could use those paintings to pay for things.’

‘I’m sure my Momma would be saying, ‘Boy, what are you doing with all that junk? What’s that tire doing piled up there on top of everything? Get all that trash out of the living room!’ But I started to think about just being able to play.’

The packs, however, paid Taylor back in kind. They helped jump-start an understanding of how the highly personal, spontaneous-seeming language of his painting might translate into three dimensions, generally through near-worthless consumer materials—snack boxes, toilet-paper tubes, tires, lamp shades, mannequin heads, figurines, furniture parts, suitcases, toy cars and airplanes, scavenged from second-hand stores and swap meets but also directly from pavement.

Before we headed to Pasadena that day, Taylor had picked me up at my hotel with the twisted remains of a rooftop television aerial jammed into the footwell behind the front seats, a spiderlike relic of Americana that he had spotted beneath a highway overpass and hopped out to collect. After we pulled up to his house in West Adams, we wrenched it out of the car and he tossed it into a willow bush in his front yard for safekeeping.

‘It’s funny. I’m sure my Momma would be saying, ‘Boy, what are you doing with all that junk? What’s that tire doing piled up there on top of everything? Get all that trash out of the living room!’ But I started to think about just being able to play. It was like me taking baby steps, figuring out if I’d like it. You never know what people are going to think, but I really don’t think about that now. I just make shit.’

The work connects Taylor to a long, rich history of West Coast assemblage, much of it pioneered by African American artists—Outterbridge, Betye Saar, Noah Purifoy, and John T. Riddle, along with artists like Ed Kienholz, George Herms, Bruce Conner, and others who began in California before moving east, like David Hammons and Melvin Edwards. Taylor, who keeps widely disparate art influences in a kind spin cycle in his mind (in his downtown studio I spotted one stack of books that included volumes devoted to Paul Thek, Joseph Cornell, Alex Katz, Richard Prince, ancient Egyptian art and classic Southern Pacific freight trains), says he also sometimes thinks about the work of Isa Genzken and Jimmy Durham when making sculpture.

‘In the beginning it was this thing of, if you didn’t have a gallery, you just tried shit a lot of times, you know what I mean? You had a lot of freedom. For a while I also had a Dodge pickup, which got stolen from a parking lot when I was in New York. But when you have a pickup you just pick up stuff in a heartbeat and think about what you could do with it. It’s like you can’t even help it, you know?’

His pieces, which have featured as supporting acts in several exhibitions over the years, including a 2012 spotlight at MoMA PS1, have grown more varied and involved over time. Some are tiny and gesturally simple (a small, black Volkswagen Beetle toy glued to a sandpaper road, affixed with two bright yellow paper cones for headlights, at once comical and unexpectedly ominous—who might this car be following?) and others are like instantaneously conceived readymades (a golf club affixed with a barbeque grill, making for something resembling an antenna receiver of American leisure and privilege.)

Like Taylor’s paintings of his family and friends, of Black celebrities and historical figures, of people he encounters on the street, the sculpture often combines a material and formal joy with a faint but palpable sense of unease, of some precarity waiting just around the next corner.

‘Taylor depicts Black history the way many Black people actually experience it: as simultaneously change and stasis, revolution and stagnation, one step forward, two steps back,’ wrote Zadie Smith in an essay about his work for a 2018 Rizzoli monograph, also published in The New Yorker.

And in some pieces that he had underway during my visit in October, the presence of the shadow, by being hidden barely at all, seemed even more at one with the work. A sculpture made of what appeared to be a plain metal clothes rack hung with freshly laundered suits and shirts, possibly evoking Cady Noland, becomes, on second look, something else entirely—hanging casually and anonymously among the business attire is a Ku Klux Klan robe.

Taylor explains the genesis almost matter-of-factly, the way he tells most stories about his youth.

‘One day when I’m about twenty I’m working at a dry cleaner, owned by a family that we knew in Oxnard, where I grew up. My job was putting the plastic over the clothes. And one day I’m doing it and it’s boring and I’m zoning out, you know, and all of a sudden I come across a Klan uniform—just hanging there on the rack in the middle of all the suits and shirts! I saw it and I pulled it out and looked at it and went ‘Woah! What the fuck?’ And then I just draped the plastic over it and kept on working. And I didn’t ask anybody how that robe got there. I didn’t even tell anybody, but I’ll tell you: I never forgot it. I kept working at the store after that. I mean, it was a job. And I thought later, ‘Well, maybe dry cleaning a Klan robe was just a job for them, just like any other clothes.’ And this wasn’t the Deep South or anything. This was California, man—in the Eighties!’

‘Sometimes I just want to get in a zone now and go somewhere else and do things I don’t even know if I know how to do.’

In conversation, Taylor is loquacious and funny and generous, but when it comes to being pressed to delve too deeply into motivation and meaning, he reminds me somewhat of the painter John Wesley, whom I once interviewed for more than two hours without getting him to say much of anything about why he chose to paint the things he painted. (The novelist Hannah Green, Wesley’s wife, said he made it ‘a rule not to talk about his work and above all not to catch himself sounding eloquent.’) Taylor is ultimately a little more forthcoming than Wesley. But he, too, nurtures a deep suspicion of talking work out, maybe in part because of the danger of over-simplistic readings of work that Black artists have long faced from white audiences.

On the way to the flea market, he told me that it still surprises him a little when he is described as a portraitist or even as a figurative painter, though he has mostly painted for the last three decades and has depicted mostly people, domestic interiors and the built world in his work. As he once said to fellow Angeleno artist Charles Gaines, reductive art-historical classification will always happen because it’s helpful: ‘When you go to the supermarket you want to know where to go for milk.’

But as he gets older and finds himself for the first time in his life without financial pressures (‘My first brand-new car was three years ago, and I’m about to turn 63 years old, man!’), he said: ‘Sometimes I just want to get in a zone now and go somewhere else and do things I don’t even know if I know how to do. Sculpture and painting on things and putting it all together. Like I don’t even care what people are going to think, you know? In Oxnard I went to school with the pro golfer Corey Pavin, he was about my age, and I’d go over to Danny Okamoto's house and see him playing at Eastwood Park, hitting the ball over and over, figuring out new ways to get better, and then one day I start reading about him in the newspaper. That made a big impression on me. It was about flat-out persistence, man, doing the thing over and over until you figure out how to do it better.’

We had finally arrived at the Rose Bowl, whose vast parking lots seemed suspiciously unoccupied. Taylor pulled up to a lone security guard, who explained that the market was unexpectedly closed that Saturday for repairs around the stadium. ‘Aw, man, you gotta be kidding me. I wanted to show this New Yorker what a swap meet’s all about.’ We drove around for a while hunting for minor swap meets before finally declaring defeat and heading to a Carl’s Jr. to get burgers for lunch.

As we ate, I asked Taylor what he felt he needed as an artist at this point in his career. He did not have to pause to think.

‘Now? Time, man! That’s the only thing. There were a lot of years when all I had was time because nobody really cared what I was doing. And now I’m so busy it’s hard to just sit and think and do what I want to do anymore. Or do anything. I lost a crown in my dental work the other day, and I’ve still got the damned thing right here in my wallet, trying to find time to get to a dentist. That’s how busy I am! I mean, I’m not complaining. People are coming at me, and I’m going places and having fun. But what I need is to just hide and get in my own head again for a while. You know what I mean?’

–

Henry Taylor’s first exhibition with Hauser & Wirth opens 26 February in Somerset where the American artist will present a major body of sculptural work and paintings.