Conversations

Echoes of a Place

Raven Chacon on transforming land, memory and political resistance into sound

Petroglyph National Monument, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo: Kenton Bueche

In recent years, Raven Chacon has emerged as one of the most quietly radical voices in contemporary music and sound art. A composer and performer who moves between graphic scores, noise improvisation and site-specific compositions, Chacon became the first Native American artist to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2022.

Chacon grew up on the Diné Nation in New Mexico and Arizona, where he began making noise music in the desert with friends, experimenting with the sonic possibilities of the land. He later joined Postcommodity, the interdisciplinary art collective known for its work about the ongoing erasure and dispossession of Native peoples. After several years with the group, Chacon turned his focus to solo musical and visual projects, eventually relocating to the Hudson Valley in upstate New York.

Since then, his work has become more expansive, often unfolding across unexpected terrains—cathedrals, mountain peaks, city rooftops, Beaux-Arts galleries—that connect the sonic characteristics of a site to its cultural and colonial past. In Aviary (2024–25), Chacon turned the American Academy of Arts and Letters in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan into a chamber of loss and remembrance, filling the neoclassical North Gallery with the trills, chirrups and calls of endangered and extinct birds.

This September, Chacon returns to New Mexico to stage his largest ensemble work to date, Tiguex, in Albuquerque, his hometown. Featuring more than 100 performers who will be situated throughout the city’s valley and surrounding mesas, the performance will encompass twenty different movements from sunrise to sunset, including a procession of lowriders and an octet of electric guitarists. On the occasion of this homecoming, the writer Jane Ursula Harris sat down with Chacon and Alexander Provan, a longtime supporter and occasional collaborator, to discuss the political dimensions of sound—whom it reaches, whom it leaves out and what it reveals about the spaces we inhabit.

Jane Ursula Harris: Alex, I thought we could start by talking about “Signaling,” the show you curated in 2022 at KinoSaito in Verplanck, New York, which included a performance of Raven’s American Ledger No. 3 (2020), a score devoted to Ida B. Wells. Like most of his works, it includes an ensemble of collaborators, in this case vocalists. Is this how you two met?

Alexander Provan: By the time I organized “Signaling,” I’d been following Raven’s work for ages! I grew up in Tucson, Arizona, and a friend who started the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson introduced me to Postcommodity in the early days, when the group was as much a noise band as an art collective. This resonated with me because I’d come to art through DIY venues that put on punk and noise shows in addition to exhibitions while acting as hubs for underground publishers and organizers. I didn’t really register the differences between these activities until, years later, I got acquainted with institutional culture in New York.

JUH: I can totally relate to this. I also came to know Raven through Postcommodity, which I loved for the way it shifted between a noise band, an activist group and an artist collective addressing Indigeneity.

AP: I got excited in part because I never knew what to expect. Postcommodity’s work was unpredictable, even unplaceable, yet always rooted in a shared sense of self-determination, which I connected to improvisation—a mode of collective expression that, to me, is as much about how to live as how to play music.

JUH: Was there a performance that stood out to you early on?

AP: MoCA Tucson presented Postcommodity’s Broom Shaman Ritual in 2007. That performance made me think about the circulation of experiences that emerge from—and constitute—particular contexts, whether historical or ephemeral, and how to engage with such work via online publishing without ending up with a simulation or an explanation for the uninitiated.

Raven Chacon, Labrador Pied Duck, 2024

Raven Chacon, Great Auk, 2024

JUH: So you two connected in Tucson?

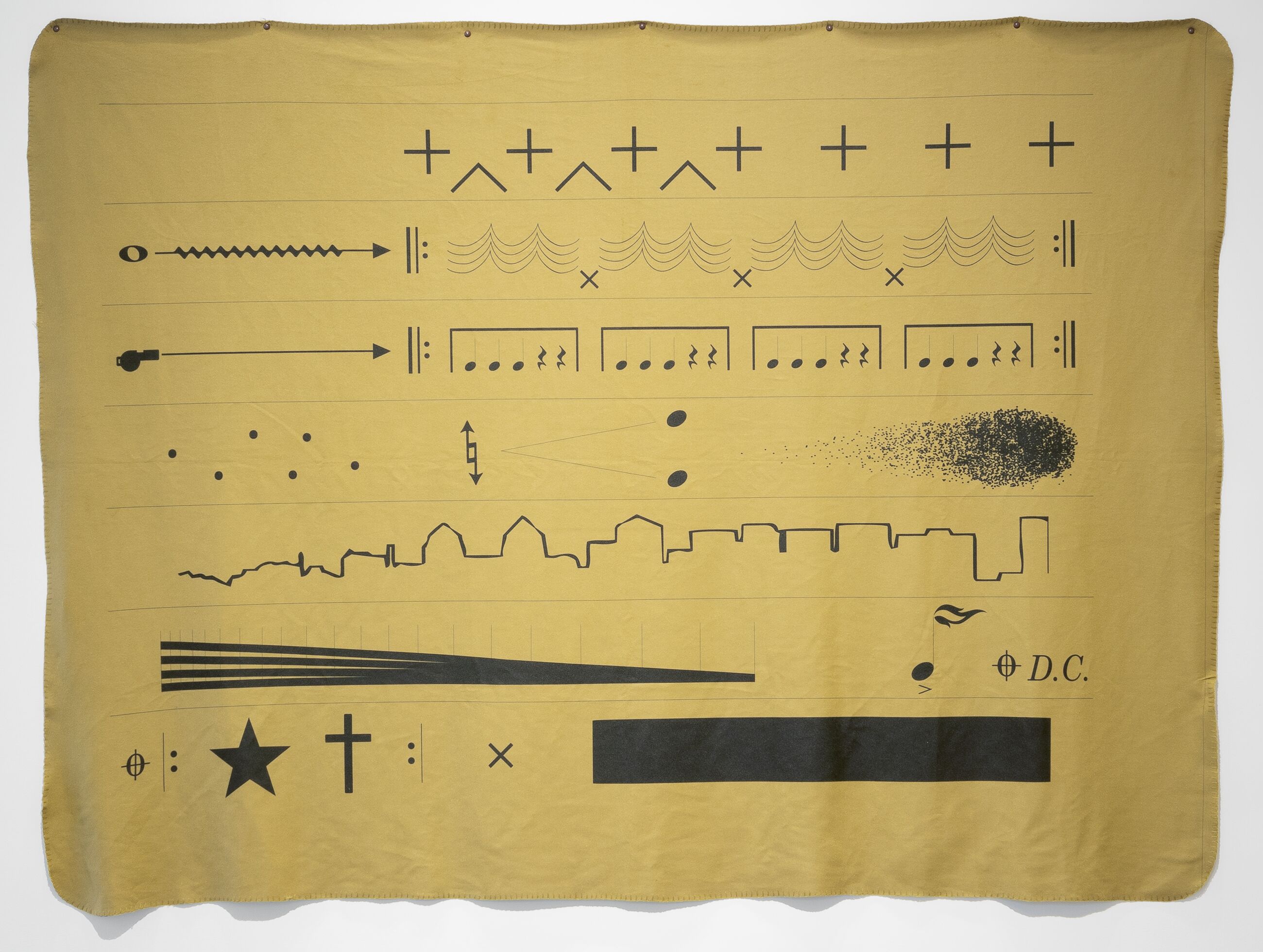

Raven Chacon: I think we actually linked up at a noise show in L.A. And then years later, toward the end of pandemic lockdown, Alex invited me to take part in “Signaling.” I had already been working on the American Ledger series, which takes the form of different flags—the U.S. flag, the Oklahoma state flag—and reshapes them into graphic scores telling the history of those places. I had written a new one, American Ledger No. 3, for Ida B. Wells in the form of the Illinois centennial flag. The score prompts two choirs to sing the words of Wells’s pamphlets calling for the end of lynching. This score hadn’t premiered yet due to the lockdown. Alex’s connections with musicians in the New York area led us to a group of singers led by the composer and performer Kinlaw.

JUH: Raven, could you talk about your use of graphic scores—visual symbols in place of traditional notation—and how they invite new ways of “reading” and performing, especially by collaborators? To me, they recall Fluxus-era work. Were there other influences?

RC: My use of graphic notation came about because of a need to notate actions where no other standardized notations existed already. For instance, different shapes of bowing patterns on a cello or changing the tone of something midway through its duration, like a flute that begins with a very pure sound then becomes raspy, and so on. I needed to make shorthand symbols for players so that every time such shifts were needed there was a prompt for the action that could be referenced very quickly. So these symbols have a consistency in their style and a logic in their appearances and placements in a score.

JUH: Some of the notations look like images of things.

RC: Right. Those evolved from my early desire to draw and reference pictographs that were left by my ancestors on rocks in my homelands. And years of doodling and mis-doodling Western standard notations as well. Fluxus artists are definitely an influence, though the text in the scores of that era is more resonant to me than their graphics. Because with text, a composer can oscillate between writing a poem or an instruction manual. Without the text, the graphics in my compositions are sort of useless—like dropping someone off in the middle of nowhere and telling them, “Play this however you want. Good luck!”

Chacon performing at Skaņu Mežs, 2024. Photo: Arnis Kalniņš

JUH: Yes, the text scores were ultimately what I was referring to. Any thoughts on this, Alex?

AP: Perhaps I’m approaching Raven’s scores as a reader rather than a player, but I see them as having an essayistic quality: The notational symbols and accompanying language act as the engine for ideas that Raven is pursuing in the work, and these get picked up by the musicians and audience. The compositions prompt a form of thinking in concert with others that goes beyond the performance of the work, especially in a piece like American Ledger—a score that doubles as a broadsheet publication.

JUH: I love this interpretation, which reveals how open the scores are and how many different ways they can be used or understood.

AP: Right, and that comes from the inventiveness of the compositions, which—like those from the Fluxus era—respond to the limits of classical music traditions. Those artists were interested in indeterminacy and in giving up or redistributing control, but they were also limited by practical realities. They weren’t getting commissions from symphonies. Raven, now that you’ve entered the world of orchestras and concert halls, I wonder how you’ve adapted your techniques and worked with musicians who may not be familiar with them.

RC: In many ways, it just means that the scale has become much larger, that there is room for more conceptual information in the score, but it is far less visible unless one studies the score. Musicians in a traditional orchestra don’t always appreciate graphic or nonmusical prompts. They’re on the clock, rehearsing under tight schedules, and many just want to play the written notes exactly as written with no surprises or questions. Pretty recently, I was working on a piece that involved an orchestra—an opera for a major museum, about the January 6 riot at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., but it was canceled right after the election.

JUH: Oh no! I hope that can be revived.

Raven Chacon, American Ledger No. 1 (Army Blanket), 2020. Graphic score

RC: Me too. I would love to work more on operas, because that medium is the ultimate container for multiple simultaneous narratives.

JUH: Another part of your work that intrigues me is your use of dissonance, feedback and amplification—distortions that echo the nontraditional listening your scores invite. Are they metaphors, predetermined or more about being in the moment?

RC: There is so much to say about all of those qualities you’ve listed. Regarding amplification and distortion, my earliest sound works considered over-amplification as a refusal of fidelity, as well as a resistance against the essentialization of a place, its people and its histories. So less about chaos and more about magnifying this refusal by just making everything louder. But yes, feedback has certainly become a metaphor, even extending over into my chamber works. Ultimately, I’m interested in the social dynamics of musicians (or nonmusicians) gathering, teaching each other, listening, learning and regurgitating in a real-time circular system.

AP: I also see your investment in attention and interaction as a bridge between music and the structures that condition how we listen to and play music—how we value or discount certain sounds, not to mention the bodies that carry them. I’m reminded of the composer George Lewis, who described graphic scores as facilitating openness by “promoting, guiding and conditioning real-time choice, thereby producing ‘changes’ in the content of the music.”

RC: Absolutely. And I suppose this happens in the improvisational half of my music-making (the other half being composition), a practice that began from attempts to create new kinds of instruments, even before I knew about the genre of experimental noise. As a young person, I wanted to make tools that would allow me to play along with the thrash metal music I loved to listen to. The crude instruments were always unwieldy and the tradition of compounding that unwieldiness with the potential chaos of guitar pedals led to my appreciation of what we might call “accidental” music. And after thirty years of doing this, I’m still continually excited about mastering a collection of tools that enable me to create such accidental (often solo) music. I am nonetheless a student of “normal” instruments too. When I want to improvise with others, say in a duo or trio, I always bring a guitar or keyboard—instruments that I’ve studied since childhood.

Raven Chacon, Voiceless Mass (2021), presented by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and First Congregational Church of Los Angeles, November 23, 2022

JUH: You have serious formal training, which really comes through. I think it also informs your DIY instruments—bone, antlers, dowsing rods, cassette-tape splicing—and your use of found sounds. What drives those choices?

RC: It is always about the goal of finding a new sound, but one can’t ignore the theater of using these objects to make music either. Years ago, I was seeking a new way to make a triad chord and began using the three prongs of a deer antler that I found in the mountains of northern New Mexico, scraping it on the concrete floors of basements I was performing in. I eventually found ways of amplifying it and then paired it with a small sheet of glass. The latter was influenced by my ongoing fear of hitting a deer while driving at night. I was thinking about the contact of that animal with the windshield and the conflict of speeds that would create that collision. I wanted to have faith that by performing it, a story of our intersecting paths could somehow be told. For me, this faith in the power of objects to provide information to us by way of their sounds—or the sounds resulting from a combination of objects—is necessary. Because we composers are just the mediators of those objects.

JUH: Many of your works are site-specific, responding to the spatial qualities and cultural histories of a place. Voiceless Mass (2021) was composed around the Cathedral of St. John’s 100-year-old pipe organ, with musicians dispersed throughout the space. This fall, you're staging your largest performance yet in your hometown. What has it been like for you to reconnect with your roots there?

RC: The new work is called Tiguex, the original name of the valley in which Albuquerque was founded. It’s designed as a composition for the whole city of Albuquerque—whether for the performers or for intentional and accidental audiences. At a minimum, it will enlist at least 100 local collaborators, many of whom I have played music with in the last thirty years, since I was a teenager making noise in the desert. It will take place on a single day this September, from sunrise to sunset, and will incorporate all geographic and cultural corners of the city: performances in the river, on a mountain peak, on a volcano, in the streets, under bridges, on rooftops—even one in the sky. It is, for me, another loop or circle in my work—bringing the music back to these places where I first learned how to make it and with all the people I made it with. Doing it reminds me of the sounds that are not experimental—the ones that are inherent to a sense of place, my origins. It's so important to remember that we all have that and can return to it when we need to.

–

Jane Ursula Harris is a Brooklyn-based writer, art historian and curator. Her essays have appeared in recent monographs on Jacolby Satterwhite, Werner Büttner and M. Lamar. She has also written for Art in America, Bomb, Bookforum and Frieze. She is a 2023 recipient of the Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.

Raven Chacon is a composer, performer and installation artist from Fort Defiance, Navajo Nation. He has exhibited or performed at LACMA, the Whitney Biennial and Swiss Institute in New York, Borealis Festival in Bergen, Norway and Site Santa Fe. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2022 and a MacArthur Fellowship in 2023.

Alexander Provan is the editor of Triple Canopy and a contributing editor at Bidoun. He is a visiting faculty member at Bard’s Center for Curatorial Studies.

–

Raven Chacon’s Tiguex debuts in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on 27 September 2025.