Portfolio

A Man Among Gods

After a life on the front lines, photographer Don McCullin finds repose in the stillness of ancient Roman statues

Minerva wearing a Corinthian helmet, Dresden State Art Collections, Germany

For more than seventy years, Don McCullin has documented the world—from the streets of London to some of the 20th century’s darkest conflicts, including Vietnam, Cyprus, Iraq, Cambodia, Northern Ireland and Lebanon. His work has shaped how generations understand the moral cost of war, and in 2019 he became the first living photographer to receive the honor of a solo exhibition at London’s Tate Britain. A longtime resident of Somerset in southwest England, McCullin has spent the past twenty-five years turning his camera toward quieter subjects: the countryside, architectural ruins and Roman sculpture. On the occasion of a survey exhibition at Hauser & Wirth New York 18th Street, McCullin reflects on the beauty, cruelty and tension that define both the classical world and his photographic work.

I staggered upon the Roman Empire accidentally. It was the timing, really—my age and where I live. I spent six decades covering war and revolutions and famines and earthquakes. It was time for me to change direction.

I live in Somerset, which is not only beautiful but also quite historic. It links back to Arthurian legends and other mythological narratives. After all those years of traveling the world, I started wandering the landscapes and the fields right behind my house. I was mainly interested in photographing the landscape in winter, when the skies were very Wagnerian—dark and moving—with the naked trees. When you see a tree without its leaves, you’re looking at the real tree.

Years ago, I was with the English travel writer Bruce Chatwin in a little Roman town in Algeria. Later, when I was kicked out of The Sunday Times and at a crossroads in my life, I thought to myself, “I’m unemployed, I’ve got no projects.” And then I thought, “Well, I’ll do something about the Roman Empire.”

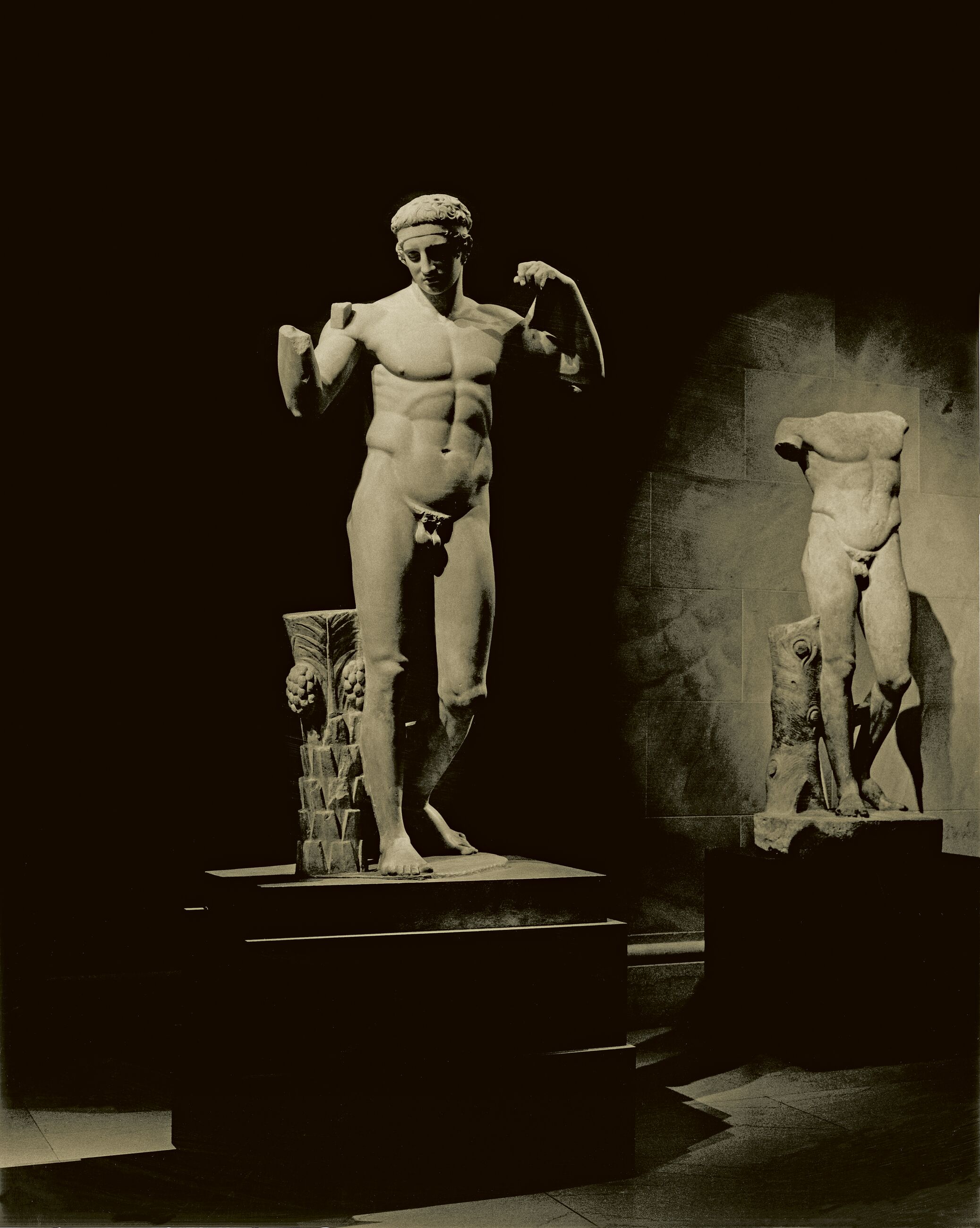

I started in Leptis Magna, the great Roman city in Libya. That was the beginning of something I hadn’t planned, and it generated a desire to photograph beautiful things. I worked my way all around the North African coast. I went to Turkey, which has some of the best museums I’ve ever seen. The lighting was incredible. Same goes for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The British Museum has a great collection but the lighting of the Romans there is very poor, I must say. In Copenhagen, I found a statue of Caligula that really surprised me—most of his legacy was destroyed, and there’s not much reference to him in museums.

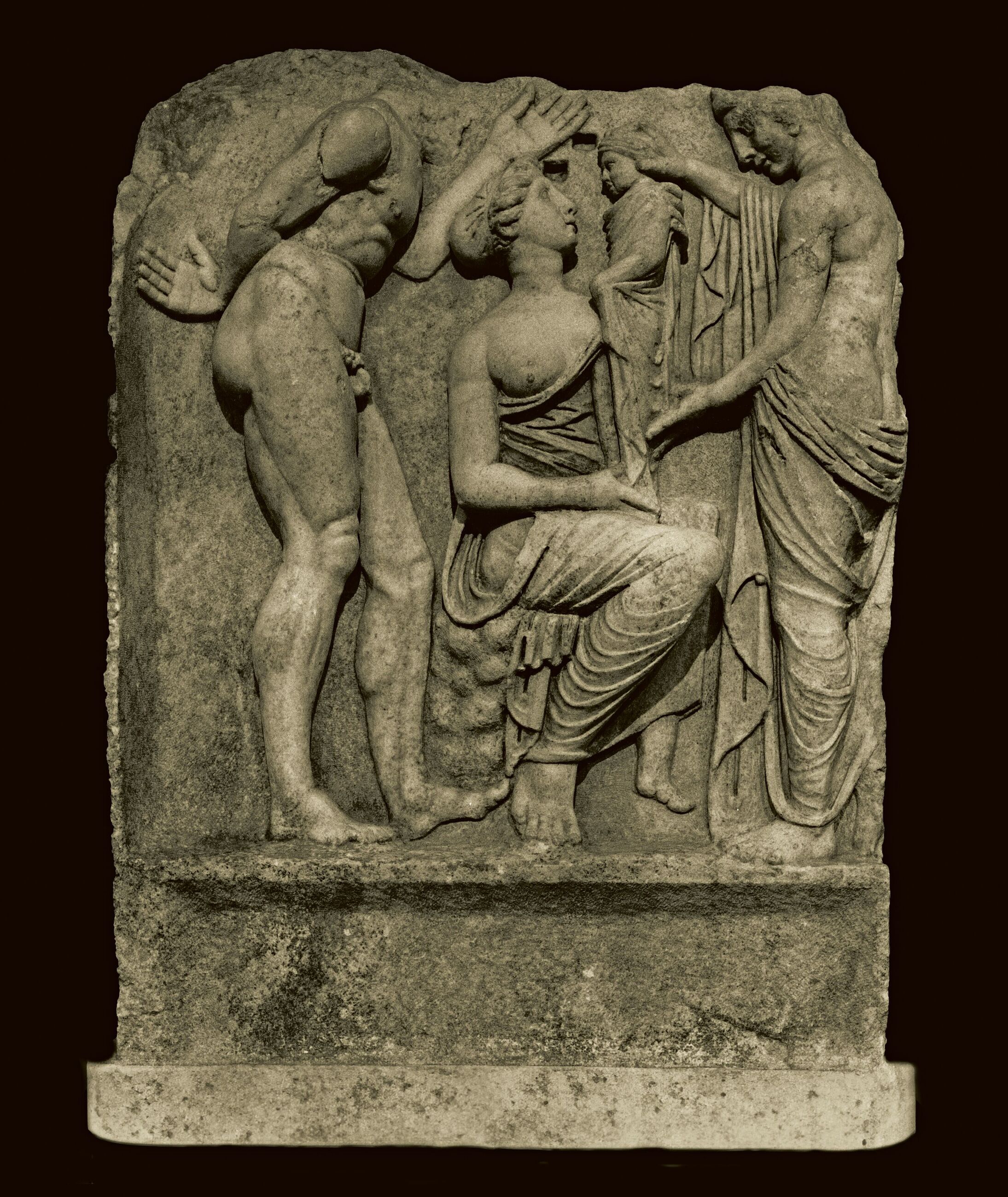

It’s now been twenty-five years of focusing on statuary and the ancient past, and I’m still hooked. Just a few weeks ago, I went back to the historic city of Palmyra. When I stand in front of these great memorials, I think two things. First: “My God, that’s amazing.” Secondly: “Hang on—it was at the cost of great suffering.” The Roman world is remarkable, but all the stone that created the cities and the marble figures came at the expense of people’s lives. So many quarry workers were prisoners from various Roman wars and died by the thousands. Even so, when I walk into museums, it’s impossible not to fall into the arms of these great, seductive creations.

With each sculpture, I want the background to vanish into darkness so that the work becomes a holy-like image. There’s a statue of Aphrodite I photographed in Tripoli, Libya. When I look at her, I think to myself, “She looks like every other naked woman I’ve seen in my life.” What was so special about Aphrodite? It’s hard to fathom that one, but the statue is stunning. And that’s my aim, for people to say, “Oh my God, how beautiful.” The statues are silent, but they speak in other ways. I want to make the marble sing.

I’ve traveled to more places than I ever thought possible, both extraordinary and unthinkable. I’ve been to so many muddy, infested jungles and to some of the worst hospitals in the world. I’ve had two toes chopped off. I’ve had cerebral malaria. Endless broken ribs. Open-heart surgery. But I didn’t set out in my life to concentrate only on pain. I’m allowed occasionally to escape and to clear up my soul and conscience and to enjoy myself in photography. It has not come cheap, but I feel incredibly privileged to have had the opportunity of this journey in my life. I’m just an ordinary man, really, and I have no intentions of stopping.

—As told to Dea Vanagan, May 2025

Aphrodite, found in the Hadrianic Baths of Leptis Magna, Tripoli Castle Museum, Libya

Cuirass bust of Caligula, New Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark

Diadoumenos, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Hercules wrestling with Libyan Triton, Wilton House, Salisbury, United Kingdom

Nymphs with baby Dionysus, Aphrodisias Museum, Turkey

Medea Sarcophagus, Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany

Bearded Hero, Dresden State Art Collections, Germany

Artemis and Iphigenia, New Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark

Apollo Belvedere, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps, Rome, Italy

–

Sir Don McCullin CBE is a photojournalist internationally acclaimed for documenting conflicts and humanitarian crises of his time, as well as contemplative subjects such as still lifes, landscapes and archaeology. McCullin combines raw compassion with a refined artistic sensibility, capturing the world’s harshest realities and its profound beauty.

–

Images in this article also appear in the recently published monograph Don McCullin: The Roman Conceit (London: GOST Books, 2025).

“Don McCullin: A Desecrated Serenity” opens 3 September 2025 at Hauser & Wirth New York 18th Street.