Essays

Past Lives

Canada Choate maps the unlikely art histories of New York’s 32 East 69th Street

Martha Jackson in the gallery with her pet macaw, Chuckie, ca. 1962. Courtesy Martha Jackson Gallery Archives, University at Buffalo Anderson Gallery, State University of New York at Buffalo

“A building,” the architect Rem Koolhaas once said, “has at least two lives—the one imagined by its maker and the life it lives afterward, and they are never the same.” In his landmark manifesto Delirious New York, Koolhaas described Manhattan’s buildings in particular as wildly accelerated accumulations of such unforeseen lives, the island “covered with several layers of phantom architecture in the form of past occupancies.”

The five-story town house that stands at 32 East 69th Street, just off Madison Avenue, has never been an architecturally famous building, nor has it ever been a regular stop on any tourist itinerary. But over almost a century and a half of existence, it has taken on so many different identities and physical forms that it has functioned as a case study of Koolhaas’s phantom-architecture paradigm and practically raises the ship-of-Theseus question, transposed to Manhattan-ese: If a building has all of its parts replaced one by one until no original part remains, is it still the same building?

What follows in this essay is a capsule history of 32 East 69th Street’s unlikely Zelig life from the late 19th century to the early 21st, a history in which the town house became a crucible of art and of city lore.

Exterior of building as a brownstone residence, 1946 © Milstein Division, The New York Public Library. Photo: Wurts Bros

Built in 1880 on farmland sold by the son of Scottish immigrant Robert Lenox—who once owned everything from 68th to 74th Street and Fifth Avenue to Park—32 East 69th Street began its life as a Queen-Anne-style brownstone, one of many in the neighborhood as wealth began to flow northward and mansions began to rise along Fifth Avenue and near Central Park.

The architecture firm of Lamb & Rich designed the building for Anthony Mowbray, an architect turned real-estate developer who became one of the most active builders on the Upper East Side before the turn of the century. While the identity of the town house’s original owner is buried in the city’s undigitized records (the family name seems to have been Chamberlain), the 14,000-page-long “Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide” of 1905 announces the building’s passing into the hands of a Louis G. Schiffer, who might have worked in finance. In the years between the house’s construction and Schiffer’s purchase, the population of the city approximately doubled. Many of these new New Yorkers were immigrants, like Dikran G. Kelekian, a revered and powerful Turkish-Armenian dealer of Islamic and ancient art who became the building’s next documented owner (and whose regal 1943 portrait by Milton Avery now resides in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Kalekian died eight years later in a fall from the twenty-sixth floor of the Hotel St. Moritz on Central Park South).

In a photograph taken in 1946, the town house remains much as it appeared when it was first built, its stoop stairs and double-stacked square bay windows set back between its imposing neighbors on either side. That same year, it was altered for the first time by architect Zareh M. Sourian, who in addition to renovating the interior to accommodate offices created a new exterior for Kelekian—a modification that would become momentous, setting the stage for a major chapter of 20th-century art history.

Exterior view of “RETROaction,” 2023-24, Hauser & Wirth New York, East 69th Street, featuring Charles Gaines, Submerged Text: Signifiers of Race #3, 1991. Photo: Matt Grubb

Moving the gallery to 69th Street confirmed Jackson’s total adoption of a life in art. The space would serve not only as the business but also as her residence—she lived, as they say, above the store.

If Sourian made the set, painter and teacher Hans Hofmann helped with the casting. Among his students was a forty-two-year-old Buffalonian named Martha Jackson who had moved to New York in 1949 with dreams of becoming an artist. Hofmann, who quickly recognized her eye and knew that she had means well beyond most struggling artists, advised her to quit painting and open a gallery. In 1953, with funds inherited from her grandmother, she began her namesake enterprise on East 66th street. For the next fifteen years, the Martha Jackson Gallery and the town house at 32 East 69th, where she would relocate in 1956, became a pivotal node in the development of second-generation Abstract Expressionism, so-called Neo-Dada, Happenings, gestural figuration and numerous other currents in contemporary art.

From the outset, Jackson took risks, and East 69th Street became known as a hotbed for experimentation. During her first year as a gallerist, she convinced the Art Institute of Chicago to mail her a body of Antoni Tàpies paintings—then on display at Marshall Field’s department store—and gave the Catalonian artist his first show in New York. In 1955, she organized “German Painting Today,” the first American exhibition of German artwork since the end of World War II. In a predominantly male art scene, she took on a host of female artists, including Barbara Hepworth, Grace Hartigan, Louise Nevelson and Lee Krasner, whose triumphal 1958 exhibition at the gallery cemented her reputation as a painter in her own right after her husband Jackson Pollock’s death a year and a half earlier.

Moving the gallery to 69th Street confirmed Jackson’s total adoption of a life in art. The space would serve not only as the business but also as her residence—she lived, as they say, above the store. Katherine Goodman, one of Jackson’s first employees, recalled how her boss dreaded the end of the workday, when she would be left alone with the art and Chuckie, her red macaw. If she’d had it her way, the space would always have been filled, not only with art but with artists, some of whom were her closest friends. Concerned by their penury, Jackson adopted the French gallery model and offered stipends to gallery artists so they could quit their day jobs. One such beneficiary was Jim Dine, whose life was changed by a $4,000 advance from Jackson in 1955.

In the spring of 1960, Dine and other artist friends of the gallery—Robert Rauschenberg, Jean Tinguely and Louise Nevelson, to name a few—participated in “New Media—New Forms,” an early presentation of assemblage and Neo-Dada that was so successful it was mounted again later that year. As many art historians have pointed out, the exhibition predated both the Museum of Modern Art’s “Art of Assemblage” and Sidney Janis Gallery’s “New Realists,” and was genuinely groundbreaking.

Invitation to the opening of Don King’s offices, September 1, 1977

View of “Exemplary Modern: Sophie Taeuber-Arp with Contemporary Artists,” 2023, Hauser & Wirth New York, East 69th Street, featuring sculptures by Nicolas Party. Photo: Thomas Barratt

It’s hard to imagine 69th Street as a cheap alternative to midtown, but that’s exactly what it was for legendary boxing promoter Don King, who purchased Jackson’s town house from Anderson after a scandal (one of many) forced King to downsize from a Rockefeller Center penthouse.

Critics were often stunned by the sheer volume and variety of works that Jackson brought together in the rooms of the gallery. In a review of the 1960 show “New Media—New Forms” in The New York Times, John Canaday exclaimed: “Mrs. Jackson has put on display just about the gol’ darnedest collection of seventy-two objects that you ever saw in your life.” An installation image shows the gallery’s parquet floors and white walls packed with sculptures and paintings, including Robert Indiana’s French Atomic Bomb (1959), assembled from rubbish scavenged around the Upper East Side, and Bruce Conner’s webbed bicycle wheel Spider Lady (1959). Claes Oldenburg’s study for the show’s poster, now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, conveys the energy animating this new generation of artists: On a torn-out piece of newspaper, radiating drips of black ink spell out the show’s title in four strata, rhyming with 32 East 69th’s four stories.

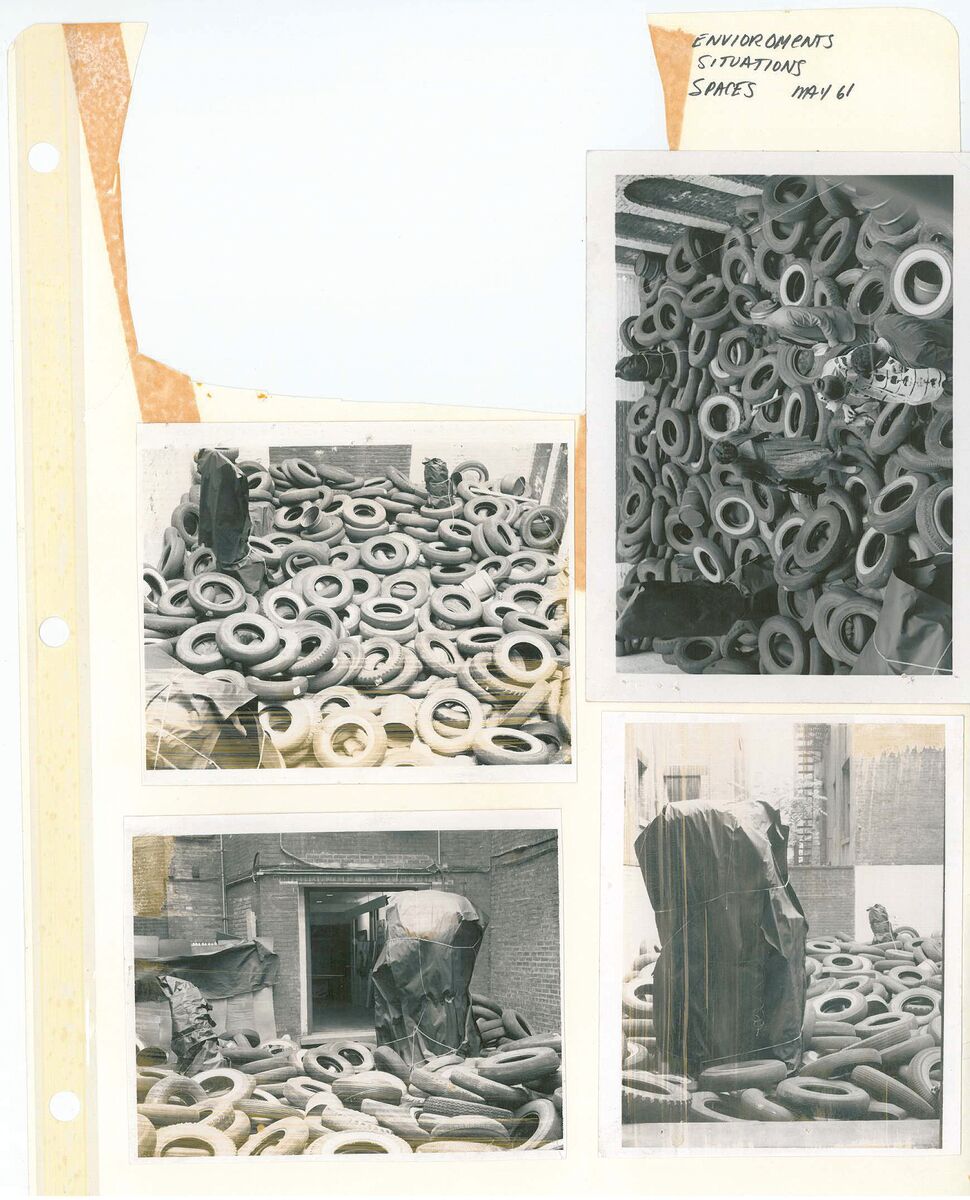

Jackson would push the junk aesthetic even farther in 1961 with the exhibition “Environments, Situations, Spaces,” featuring Allan Kaprow’s traversable tire heap Yard, and the first iteration of Oldenburg’s Store.

For Yard, Kaprow covered Jackson’s outdoor sculpture collection in black tar paper and filled the courtyard with used tires that visitors were welcome to climb and manipulate as they pleased. Jill Johnson of The Village Voice pointed out the seeming contradiction of the gritty art and the tony surroundings, writing that “the ‘terrible children’ invaded Martha Jackson’s Gallery last May and June with more of those baffling noncommercial commodities, things you can’t use or sell or label even, which nobody could be too clear about why they should be encouraged or endured much less considered the prestige items they obviously are, or else why would Miss Jackson (whose commercial acumen is well known) clutter up her fashionable yard?”

Perhaps it was Jackson’s embrace of art melting into life—her disinterest in traditional family structures back in Buffalo, her combination of her home and her business—that made her sympathetic to these young artists’ desire to fuse the two.

The next fifteen years brought more change, much of it spurred by Jackson herself. One such innovation was the gallery as publishing house and media company. In 1964, she founded Red Parrot Films—named for her beloved Chuckie, of course—and began making artist documentaries. While the rest of the Upper East Side was gravitating toward the postmodern irony of Andy Warhol, who was at work twenty blocks north, Jackson showed the work of Bob Thompson, whose paintings reinvented Renaissance and Baroque motifs. Artist Gerald Jackson remembers Thompson’s show being such a hit that “everybody was standing outside and they were all yelling, “Where’s Bob? Where’s Bob?” Thompson’s death in 1966 made his show at 32 East 69th his last.

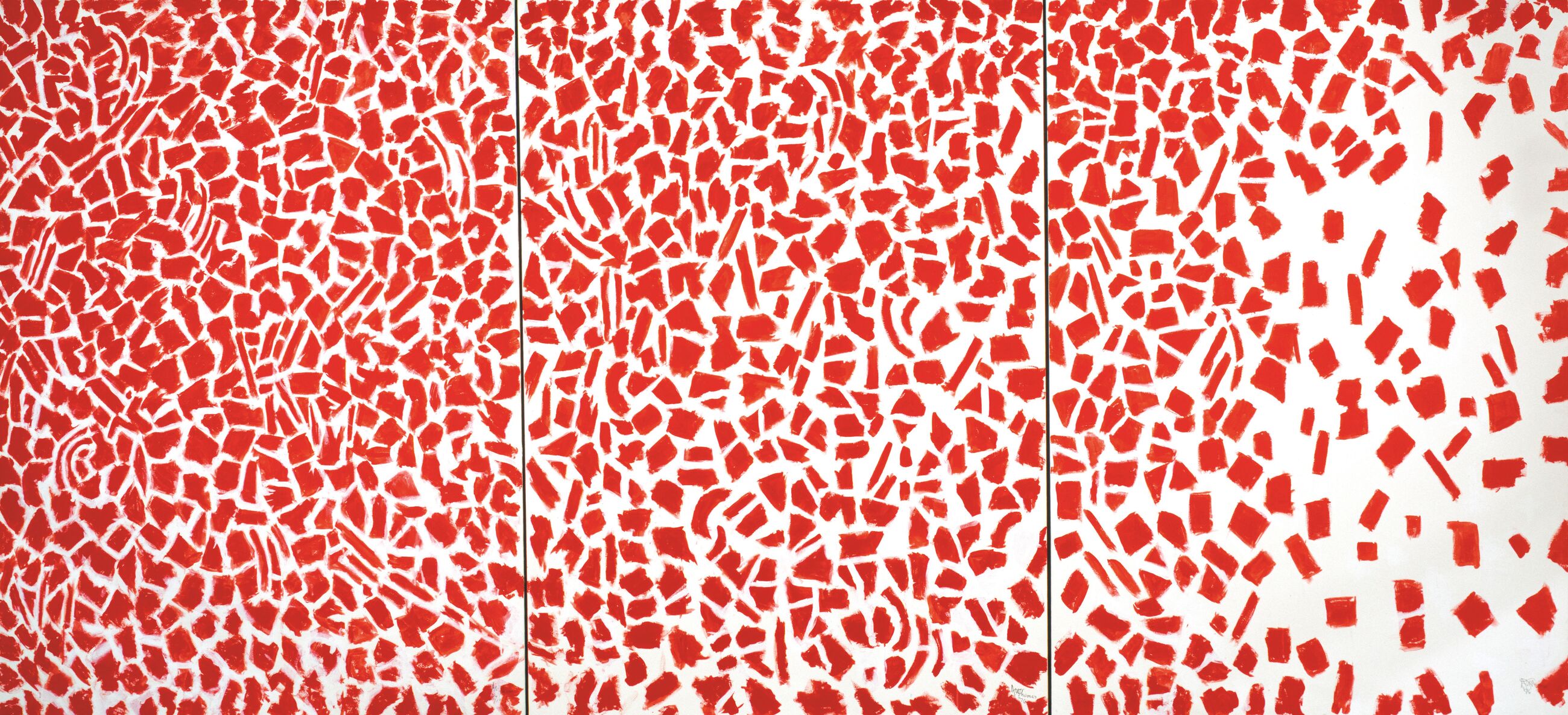

Alma Thomas, Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music, 1976. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY © 2025 Estate of Alma Thomas (Courtesy the Hart Family) / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When Jackson died in 1969, the gallery went to her son, David Anderson, who continued to show gallery standouts like Lucio Fontana, Karel Appel and Julian Stanczak through 1976. The highlight of the gallery’s late period might be Alma Thomas’s momentous, thirteen-foot-long Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music (1976), now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, shown at what was also to be Thomas’s final outing.

It’s hard to imagine 69th Street as a cheap alternative to midtown, but that’s exactly what it became for legendary boxing promoter Don King, who purchased Jackson’s town house from Anderson in 1977 after a scandal (one of many) forced King to downsize from a Rockefeller Center penthouse. Despite this setback, King was then at the height of his fame, having just two years earlier promoted the blockbuster Ali–Frazier fight that became known as the “Thrilla in Manila.” As improbable as King’s time in the building may seem, some aspects of being a boxing promoter were not so different from those of being a gallery owner: Both assumed the immense risk associated with putting on shows and both, in highly unpredictable businesses, survived by virtue of their savvy in spotting talent.

King’s sense of style, palatial and flashy, thoroughly transformed a building that had once been a midcentury showroom. The invitation to the opening of Don King Productions featured his smiling portrait in purple framed by an expanse of gold and his company’s logo, a red crown over the single word Don. King used the town house for meetings with famous clients like Ali and Michael Jackson, whose tour he was hired to promote in 1984. That year, a sports journalist who sat in on one of these meetings reported that “the room looked as though it had been furnished as a Hollywood movie set. Thick red carpet, plush leather sofas, a mirrored ceiling and fully mirrored wall, an enormous desk and glass-topped conference table, three television sets, and two huge American flags.”

King’s flamboyance got him in trouble with the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1990 when he commissioned an unauthorized alteration to the facade of the building, described by the Times as “rococo metal grillwork and ornamental glass that cover the lower two floors of the building.”

View of “Lorna Simpson: 1985–92,” 2022, Hauser & Wirth New York, East 69th Street, featuring Simpson’s Waterbearer, 1986. Photo: Matt Grubb

In 1998, David Zwirner and Iwan Wirth purchased 32 East 69th Street as a showroom for their collaborative venture Zwirner & Wirth and undertook a thorough reimagining of the town house by Annabelle Selldorf, the German architect known for her cool minimalism and deep experience in the New York art world. In addition to completely redoing the facade in cement stucco and stripping what King had added to the interior, Selldorf installed an elevator between the gallery and living space, finally collapsing private and public, art and life.

The renowned New York interior decorator Ricky Clifton took care of the furnishings and wall treatments, saying he conceived of the project as an unconventional Gesamtkunstwerk. Recounting his design choices more than two decades later, Clifton nonchalantly listed his unusual treatments, some of which Don King might have endorsed: “Living room was purple, hallway was chartreuse, big Jason Rhoades sculpture was hanging down, bedroom was black, dining room was silver.”

A recorded voice included as part of Pope.L’s work spoke to ecological crisis, suffering and modern racism. “Re-arrange the tires—have faith and wait,” the voice said. More consequentially, it exhorted: “Re-arrange your morals.”

Installation view of Allan Kaprow’s Yard, 1961, in “Environments, Situations, Spaces,” Martha Jackson Gallery © Glenstone. Courtesy of Martha Jackson Gallery Archives, University at Buffalo Anderson Gallery, State University of New York at Buffalo

Installation view of Yard (To Harrow), 2009. Staged by Pope.L for the exhibition “Allan Kaprow: Yard,” Hauser & Wirth New York, East 69th Street © Allan Kaprow Estate. Courtesy Hauser and Wirth. Photo: Hannah Heinrich

When Hauser & Wirth debuted its first American gallery space at 32 East 69th Street in 2009, art’s dissolve into the domestic had become fully part of the building’s soul. Ursula Hauser, a cofounder of the gallery and its matriarch, briefly lived upstairs and the space once again welcomed the public, opening with a reinterpretation of Kaprow’s Yard by Pope.L that filled its bottom floor with tires from wall to wall. The gallery, dimly lighted, reeked of rubber and grease. Pope.L’s tires—not neutral castoffs but signifiers, at least in part, of the environmental damage to the planet well underway by the mid-20th century—were accompanied by racks of wrapped forms redolent of body bags, perhaps a reference to the violence against African Americans rampant in 1961 when Kaprow’s piece debuted. A recorded voice included as part of Pope.L’s work spoke to ecological crisis, suffering and modern racism. “Rearrange the tires—have faith and wait,” the voice said. More consequentially, it exhorted: “Rearrange your morals.”

As 32 East 69th Street begins its next life—Hauser & Wirth sold the building earlier this year after organizing more than sixty exhibitions there, many of them critically acclaimed—its future is as uncertain as any of ours, perhaps appropriately so for such a shape-shifting space. It is, as Koolhaas wrote, part of the fabric of a “theoretical Manhattan, a Manhattan as conjecture,” of which the present city is only “the compromised and imperfect realization.”

–

Canada Choate is a writer, editor and researcher who explores art’s intellectual histories. She was a 2021–22 Helena Rubinstein Fellow of the Whitney’s Independent Study Program. Her work has appeared in Artforum, Flash Art, The New York Review of Architecture and Broadcast. She lives in Queens, New York.