Diary

An Imponderable Monsieur

Barbara Chase-Riboud’s memories of Alberto Giacometti

Ernst Scheidegger, Annette Giacometti sitzt Modell im Atelier in Stampa, (Annette Giacometti posing as a model in the studio in Stampa), 1961. Photo © 2025 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich. Artwork © Succession Alberto Giacometti / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY 2025

In Paris in the early 1960s, two artists at opposite ends of their lives met twice: Barbara Chase-Riboud, an American in her twenties, newly graduated from Yale, just beginning her life as an expat artist; and Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966), the Swiss master, whose attenuated figures had already become canonical. Their encounters left an impression on Chase-Riboud that has stayed with her for more than half a century.

In recent years, their sculptures have been exhibited together, illuminating the formal connections and emotional currents that link them across generations. Both artists are celebrated for sculptures that merge structure and surface, as well as literature and myth, in vertical, monumental forms—and they share a deep interest in drawing, painting, printmaking and prose.

On the occasion of “Alberto Giacometti: Faces and Landscapes of Home,” curated by Tobia Bezzola, opening at Hauser & Wirth St. Moritz in December, Chase-Riboud spoke recently with Ursula about her encounters with Giacometti—her memories of his fragility, humor and “quiet majesty”—about the similarities and stark differences in their work, and about the Bregaglia and Engadin valleys in Switzerland, which were central to Giacometti’s life.

I first met Giacometti when I was married to Marc Riboud, a photographer who was a protégé of Henri Cartier-Bresson. It was 1962, and I was a young bride—a baby, really. They were close friends, and once, before Marc left on a trip to Vietnam, he said to Henri, “Take care of Barbara. She doesn’t speak a word of French.” Cartier-Bresson said to me, “Let’s go to Giacometti’s studio. Have you ever met him?” And I said, “Of course not.”

Alberto Giacometti, Tête au long cou (Head with Long Neck), c. 1949 (cast 1965) © Succession Alberto Giacometti / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY 2025

Barbara Chase-Riboud in her studio, Paris, 1973 © Martine Franck/Magnum Photos

I was very familiar with Giacometti’s work—I was straight out of Yale and au courant with everything he had done. I’d imagined I was going to walk into a proper French château that day, with a gravel walkway and flowers. Instead, I entered one of the poorest habitations I had ever seen in my life—a ramshackle atelier made of wood and patched everywhere. The place was literally falling down. Inside, I encountered this Egyptian mummy covered in white plaster from head to toe, curls of hair all over, with a trail of cigarette smoke rising from his head. It was the great Giacometti, and that was how I saw him for the first time.

Barbara Chase-Riboud at the Giacometti atelier, Giacometti Institute, Paris, 2021 © Succession Alberto Giacometti / ARS, NY, 2025. Photo: Marilyn Paed-Rayay

After Cartier-Bresson explained who I was, the two men immediately went into a long conversation in French, too fast for me to follow. The studio was tiny—no more than twenty-five square meters—located at the end of a little alleyway that was surrounded by other small wooden huts. This was where he lived all his life. I realized this was another world, another epoch. As famous as Giacometti was, he seemed to me an imponderable monsieur—funny and somber at the same time. I could barely follow the repartee between him and Cartier-Bresson, so I just sat and listened. I can’t say I had a conversation with them. I was referred to as la petite Américaine, the young bride of Riboud who didn’t speak a word of French.

Ernst Scheidegger, Die ‘Femme au chariot’ (1942/43) im Atelier in Maloja, 1959. Photo © 2025 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich. Artwork © Succession Alberto Giacometti / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY 2025

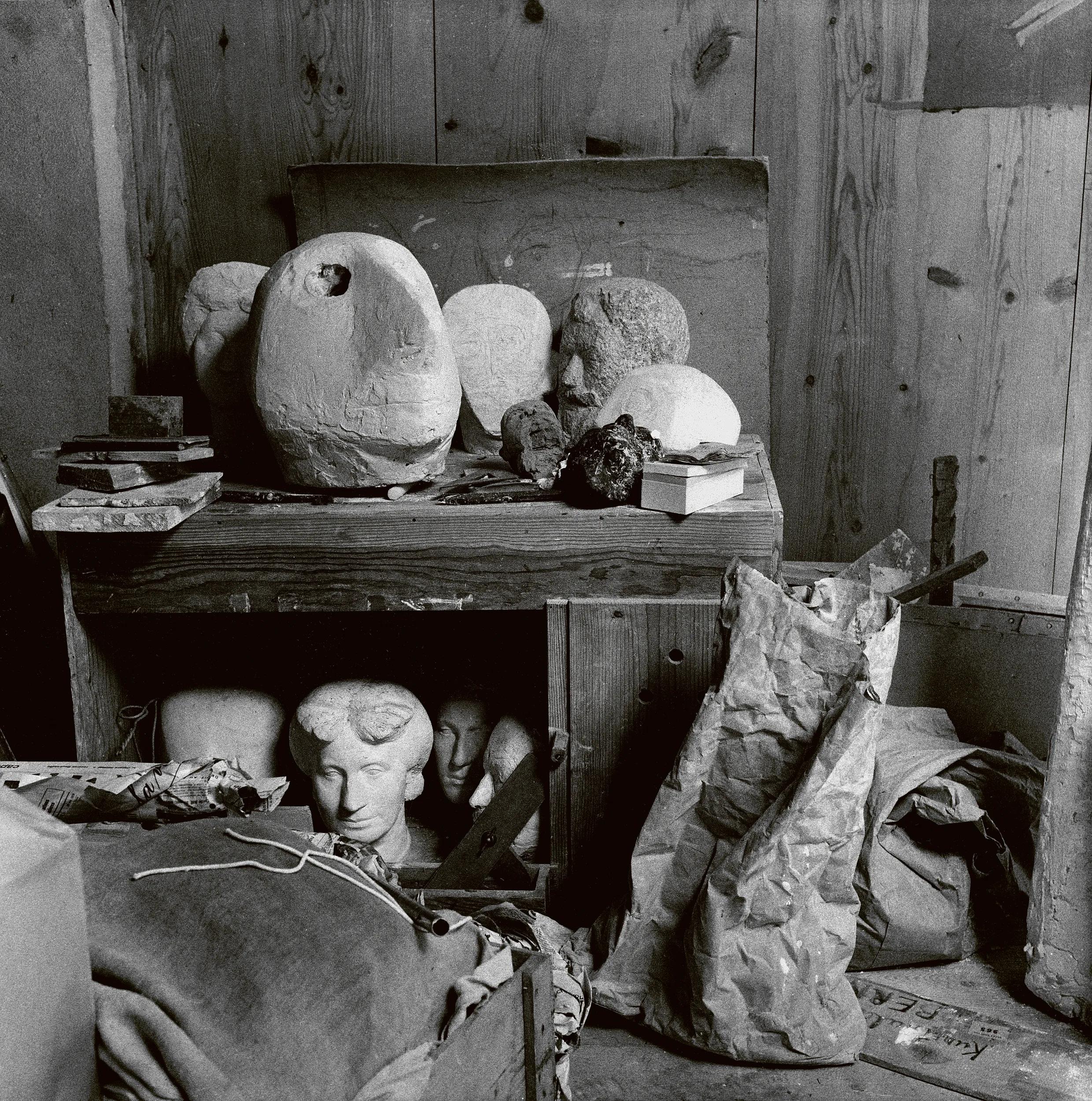

Ernst Scheidegger, Atelierecke in Maloja (Studio corner in Maloja), 1959. Photo © 2025 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich. Artwork © Succession Alberto Giacometti / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY 2025

The studio was completely covered in plaster, just like he was. That’s how he worked. There were figures everywhere, looming around: big, gigantic women and tiny, matchstick-size ones. A few of his iconic sculptures were there, too, all in a little room with nowhere to sit except on the bed. Outside rickety stairs led up to a small second floor, where he and his wife, Annette, lived. I couldn’t believe it—and then I did believe it. It made more sense than any other arrangement.

Ernst Scheidegger, Alberto Giacometti am Arbeitstisch in Stampa (Alberto Giacometti at his worktable in Stampa), 1964. Photo © 2025 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich. Artwork © Succession Alberto Giacometti / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY 2025

People often see a dialogue between my work and Giacometti’s, especially in the verticality. I see the connection, too, but in a very different way. The interesting thing is that I never think about the human figure when I’m working and he never thought about anything else. For me, the figure is completely abstracted. Every stele I make somehow turns out to be a personage, but that was never my intention.

Alberto Giacometti, Grande Femme IV, 1960. Collection Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler. Photo: Robert Bayer © Succession Alberto Giacometti / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY 2025

Barbara Chase-Riboud, Standing Black Woman of Venice X,Vijja (BBBA), 1969–2020. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Alex Delfanne

The Engadin itself is pure poetry, a landscape that seems to echo with the voices of Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust, Jean Cocteau and Hermann Hesse. They all loved that place. They wrote there, lived there, congregated there. Giacometti was a mountaineer; it’s the landscape where he was born and where his mother lived. I don’t really see that part of him in his sculpture, but he did make landscape paintings.

Barbara Chase-Riboud at “The Encounter: Barbara Chase-Riboud/Alberto Giacometti” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, 2023 © Succession Alberto Giacometti / ARS, NY, 2025. Photo: Sophie Elgort

When I looked through Giacometti’s archives, I saw that he would draw on anything—printed pages, typewritten pages. He wrote letters, notes, texts that weren’t quite poetry, but they weren’t books, either. The impulse to write was very strong in him, as it is in me. I do automatic writing—black drawings and white drawings that combine writing and sewing. There’s a shared gesture in all of it with Giacometti, of the hand, something inherently poetic, which of course is what poets do when they write.

When my work was shown with Giacometti’s a few years ago, I wasn’t surprised. What did surprise me were his early surrealist sculptures. I had thought of him only as a figurative, existential, poetic artist, but those earlier works were different—almost Calder-like, even funny. I hadn’t known them well, because I’d always focused on his elongated figures. Seeing these earlier pieces up close, I realized that they were closer to what I was doing than his later ones.

Barbara Chase-Riboud with sculptures by herself and Giacometti, for the exhibition “Alberto Giacometti/Barbara Chase-Riboud. Standing Women of Venice,” Paris, Institut Giacometti, 2021 © Succession Giacometti / ADAGP, Paris, 2025

My Giacometti poem belongs to a suite of poems I’ve written about other people—poets, painters, artists. It’s a book in itself, really. He is one among a crowd of personalities who have moved me to write. These poems come when they come; it has nothing to do with when I met the subjects. They’re not really elegies, not really portraits. They just arrive. They fall from the sky, and I write them down.

For Alberto Giacometti

In Karnak’s shadow

You wandered

Through Milan’s Duomo

No more than

A sprinkling

Of carborundum

With careful Swiss eyes.

“Maestro, are you lost?”

“No, only my railway ticket.”

We fed you English tea and pastry,

A sad-faced and scarred Ramses

Amongst the chattering Italians,

And drove you home

To your mother in Borgonovo.

Alberto Giacometti, Monte del Forno, 1923. Private collection, Switzerland © Succession Alberto Giacometti / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY 2025

That combination of landscape and poetry is something Giacometti and I share. It creates a kind of resonance in our work, but I’m not a mountain lady. I like oceans. Mountains make me very depressed, and the shadows they cast frighten me. The Swiss mountains to me are a place of danger, and I avoid that kind of landscape. When I made landscapes, it was during a period when I was working with animal bones—but I don’t do mountains.

I encountered Giacometti again near the end of his life, around 1964. Marc and I were in Milan, visiting the Duomo, when we suddenly saw him wandering through the aisles among all these chattering Italians. He was moving silently through the crowd and looked so displaced—like an ancient Egyptian figure, as if Ramses himself had stepped into the church. We went up to him and said, “Maestro, what’s the matter? Why are you here all alone?” He told us he’d lost his train ticket home. Someone had stolen his wallet, and he had no money, no cigarettes, nothing. I was floored—this was Giacometti! He was famous, rich even, though he never used a bank and kept his money under his mattress. Here he was, stranded in Milan like a child. We took him to a restaurant, fed him, bought him cigarettes. Then we made him tea and drove him home to his mother in the mountains. There was something about that moment that reminded me of the first time I met him—the same air of quiet majesty, this royal person moving through the world as if untouched by it. And that was the last time I saw him.

—As told to Alexandra Vargo

–

Barbara Chase-Riboud, the first Black woman to graduate from the Yale School of Art with an M.F.A., in art and architecture, is a critically acclaimed artist, poet and author of historical fiction. Her most recent exhibition, presented concurrently at eight museums across Paris, was on view from September 2024 through January 2025.