Fiction

A Fable About Colour

A new short story by Ben Okri

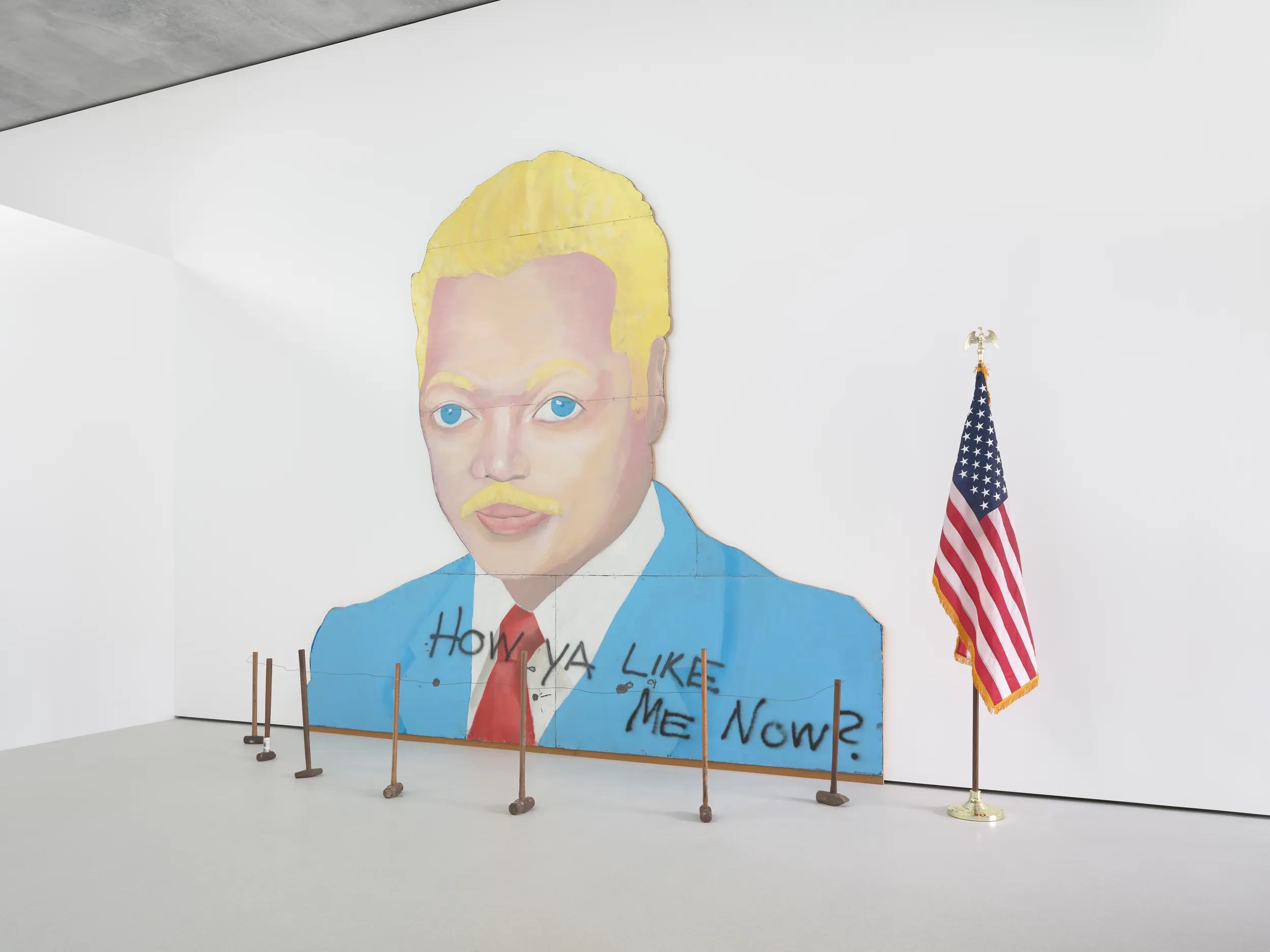

David Hammons, How Ya Like Me Now?, 1988. Courtesy Glenstone Museum © David Hammons / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Ron Amstutz

Black woke up in the morning and the world seemed good. He listened to the blackbird’s dawn chorus and the three-beat call of the blue tit. He had slept well, if briefly. The day had not yet formed. The sky was still dark as seen through the slats in his blinds. This was the best moment of the day. It was the time when he was all in himself. His mind was his and his being was his and nothing yet had impinged on his spirit. The day was clean. It would be the best it would be for the next twenty-four hours. Even his thoughts had not yet begun to spoil the day. He lay there, just before dawn, and wished in his heart that the moment could last indefinitely. But it couldn’t. Soon the house would rouse. Dawn would give way to daylight. Then the day wouldn’t be his anymore.

He rose from his bed on the floor and cleaned his teeth. Then he made himself a modest breakfast of fried eggs, a sausage, a fried tomato and some mushrooms. He had his breakfast with tea. He had a shower, got dressed and went out.

The moment he stepped outside his door his day was altered. He met a neighbour who, nodding in response to his greeting, gave him a suspicious look. With that look the day changed. Already, by virtue of being seen, he was presumed guilty of something. He was never sure what. As he went down the stairs this sense grew more concrete. It happened even when there was no one looking. By the time he got to the front door he was cautious. And by the time he had stepped out into the world he was a little timid. But he tightened his inner armour.

The air seemed to make him walk a little more stooped, as though it were pressing down on him with invisible weights. With a conscious effort, he made himself a little taller and stood straighter. He had barely left the house and entered the world but already he felt weary from the accumulated weight of the other days.

He went past people who barely noticed him. They barely noticed him but they swerved to avoid him. He felt, as he walked down the street, that something about him preceded him. It went in advance of him in all directions. Boys on their way to school peeked at him curiously.

At the bus stop people stood away from him. In the bus no one sat next to him, though the bus was full. There was much traffic and the bus moved slowly. An inspector came on board and went through the bus looking for the faces of those most likely not to have paid their fare. The inspector saw him and stopped.

“Your ticket please.”

Black brought out his bus pass and the inspector checked it against a machine thoroughly. He did it twice and reluctantly gave the pass back to Black, seemingly unable to believe that his suspicion had not been confirmed. Black had expected that the inspector would choose him for inspection. He chose no one else. Black expected it because it happened every time.

He disembarked from the bus when he arrived at the stop from which he walked to the area that would be his office for the day. It was a fairly long walk, and it gave him a chance to stretch his legs after being seated on the bus and to get some air. The air wasn’t much good, as it was always contaminated with the fumes from buses and cars. But still, it was nice to see the colours of the world, the buildings and the streets, and people on their way to work in all manner of official dresses and clothes.

In spite of the fact that he felt often as if he were invisible, Black liked looking at the world. He liked looking at people and at things. He liked shopwindows. The shoes people walked in interested him. The cut of people’s clothes and how they fitted within them absorbed his attention. He liked to watch how people walked, how they carried themselves, and above all he liked to study people’s faces. For him, the faces of people were the most interesting landscape in the world. He often made surmises from faces. He analysed them, wondered about them, made swift deductions about their lives and who they were, and often contemplated whether they were happy or not.

The faces of the world often made him feel that the world must be a difficult place for people, regardless of how successful or how poor they were. Faces told him so much. They were maps to a secret history. He had learnt how to read those maps. He had learnt how not to look at the obvious things, like beauty or youth or even freshness of skin. He had learnt to see the invisible signs on the map, the signs of fear and anxiety, of doubt and weakness. It was because he had learnt to read the signs on the map of faces that he had managed to survive. With a glance he could often read what he needed to know about a person, what they hid, what they projected.

He watched faces from inside his face. From inside the armour of colour. When he was younger, it was not an armour. It was a burden. It caused him no end of trouble. It got him picked on. It got him ignored. It got him arrested. It got him lonely. It got him without promotion and for long periods without a job. It got him passed over. But it also taught him to survive. It gave him a unique vantage point from which to study the world. As the years went past, he came to realise quite slowly that instead of being a burden it had turned out to be his greatest blessing. But it was a blessing that had its inescapable troubles. They were troubles he had to cope with every day. The years had taught him how to cope with them.

Because of the armour he had a steady place from which to study the world. He noticed that he had a fluidity in the world because of the colour. Sometimes it was an armour. But sometimes it was a camouflage. Many years ago he realised that he could pass from one kind of person to another seamlessly, without anyone noticing. He could be many people. It was one of the great liberating discoveries of his life. But it was a discovery that came slowly. It came dimly, from within what he thought was the confines of a life, the confines of colour.

It happened entirely by accident. He had been sent to meet someone at a station. He waited on the platform. While he waited, several things happened to him. The police came to him to move him on, supposing he had no right to be there. The police came again to demand his identity, supposing that he didn’t have one. Then the police came again to arrest him for a crime that, as it turned out, someone else, of a different colour, had committed. In the process, he did not manage to meet the man he was scheduled to meet and bring to his hotel. And as a result, he was fired from his job. And because he was fired from his job he became homeless. But then it occurred to him to continue his life as if he still had his job, as if he had been sent to the station to meet someone and had indeed brought that person back to his hotel. So every day he would wear his suit and his white shirt, which he washed every evening in the fountain at Trafalgar Square, and he would go to the station to wait for the man.

One day, in the course of waiting, he was taken for someone important who was being waited for himself.

“Are you Mr Arthur?” a young lady of a different colour said to him.

“Yes,” he said.

“We’ve been waiting for you a long time. Please follow me. Your taxi is waiting.”

He followed the lady to the taxi.

“You will take the taxi to the Mayfair Hotel, where you will be met.”

“Will you not travel with me?”

“No, sir. You are much too important for that.”

He got in the taxi and was driven through a light London traffic, past sights that he had seen from his endless walks, to the Mayfair Hotel. A liveried concierge opened the door for him and led him into the lobby as if he were a potentate. He was not there long. During that brief moment of waiting he managed to look around. It was the most luxurious-looking interior he had ever seen. He glanced down at his shoes. They were still black, though a closer scrutiny might have revealed a crease running horizontally on the right foot. The concierge had gone to the desk and been handed the room keys and come back. He signalled to someone. Then he went to Black.

“It is your usual suite, sir. We are having your luggage brought up. Have you had a good journey, sir?”

Black looked at the concierge, who stood at a respectful distance outside the lift. Then he nodded.

“Your easy style always fools us, sir. But our agent recognised you this time from your calm manner. We thought we’d lost you.”

The lift arrived. It was lined with velvet. The concierge indicated to Black that he should step into the lift. Black stepped in. The concierge pressed a button and skipped back out before the door shut.

“We’ll meet you upstairs, sir.”

The door shut and the lift rose noiselessly. There was a pleasant fragrance of tradition and money in the lift. In what seemed like no time, the door opened. The concierge came out of another lift with the luggage and led him to a room nearby and opened the door and nodded for Black to go in. Black stepped into the largest and most sumptuous room imaginable. It was not one room but a suite of rooms. The main one was furnished as if for a king, with its plush red sofas and the rich cluster of chandeliers, the soft thick carpet and the large clean windows overlooking a vast park with oaks and sycamores. The slippers and bathrobes in the bathroom were monogrammed. There was a dewy bottle of champagne in a bucket full of ice and the most delicious set of snacks on the round burnished table.

While he was studying the room, the concierge came in with his luggage. Without a word he began to unpack it and hang up the clothes. He opened the champagne and poured a glass. Then he called down to room service to have a certain favourite meal brought up to the room because Mr Scanton, as he was called, would be ravenous from his long journey.

“I have ordered everything for you as you like it, sir. Will you be coming down later?”

“Why not?” was all Black could bring out.

The concierge lingered by the door, as if half-expecting another request.

“And one more thing,” Black said. “Can you have them bring up fifty thousand pounds in cash? Have them put it on the room.”

“Will that be for the game, sir?”

Black stared at the concierge without saying a word. He had learned fast that everything had happened to him without his saying a word. There was no need to change now. The concierge understood his silence, gave a hidden smile, bowed and glided out of the room.

Black immediately had a bath in the tub that was so elegant and big that it seemed designed to be lived in, not bathed in. Black had himself some champagne while he bathed. The edges of the bath were filthy with the weeks of muck that came from the unwashed grease of his body. Then he cleaned his teeth and brushed his hair and oiled his skin and proceeded to investigate what was in the luggage. He found new underwear, trousers, shirts, socks, and shoes, all of the very highest quality, all monogrammed, and all fitting him perfectly. Slowly, and with muted pleasure, he became Mr Scanton.

In the luggage he found a picture of Mr Scanton with a beautiful young lady of ivory complexion. Mr Scanton seemed cautiously happy. Black wore his clothes, right down to the elastic braces that held up his trousers. When he looked at himself in the mirror, he could not believe that he had ever been someone else.

The dream that was Black faded. The reality that was Mr Arthur Scanton stood before him.

He had two more glasses of champagne, polished off the delicious finger sandwiches and the fine little madeleines and washed it all down with another glass of the smooth, clean, faintly fruity champagne. Then he went and stood at the window and looked out over the park. This life had been handed to him without a single request on his part. It was a good life. He had never known that such a life was possible. He was going to live the life as long as the life chose to live him. He felt sure that at some point in the day he had walked into a dream. There was never any need for him to wake up from it. If the dream came to an end by itself then he would wake from it. But only if the dream ended itself. Otherwise he was going to go on dreaming it.

He had always known that such a life was possible to him. He had always known that fabulous wealth was going to fall into his lap without his having to lift a finger. But those were idle fantasies with which he whiled away the difficulties of time. Sometimes, though, the fantasies were not idle and it seemed as if they were true already. Now, standing at the window, fingering the fine material of the thick curtain while looking out over the park, he began to feel that the fear of poverty that he’d had all his life was something he was going to have to overcome.

The doorbell rang, pulling him away from the curtain. He sat in a nearby sofa and felt himself sink into its softness. The doorbell rang again briefly. It was the concierge, returning with a bundle in his arm, which he put on the table.

“You have to sign for it, sir.”

“All right,” was all Arthur said, for he was now Arthur.

The concierge stood there a moment, waiting. Then, somewhat perplexed, he made to leave. But Arthur stood up abruptly, which made the concierge pause. He went over to the bundle, tore it open delicately, and regarded the crisp notes. He peeled off five hundred pounds and went over to the concierge and handed them to him.

“Make sure you look after me,” he said. “I don’t want to be disturbed. Keep the others from me.”

“The others, sir?”

“That’s right,” said Arthur, mysteriously. “The others.”

The concierge immediately understood.

“Will you be coming down for the game?”

“In a minute.”

“Thank you for this, sir. You’re even more generous than usual.”

“It’s our little secret,” Arthur said, and went to the table and poured himself some more champagne.

“I could have done that for you, sir.”

Arthur nodded. The concierge realised he was being dismissed and bowed out of the room. When he had gone, Arthur divided up the money to put into different pockets. He noticed among the things laid out from luggage that there was a fawn-coloured hat. He wore it and instantly his transformation was complete. He polished off the champagne and, taking up his room key, a card, left the room. He took the exclusive lift down to the ground floor, where he found the concierge waiting for him.

“Are we ready, sir?” he said.

Arthur nodded again. The concierge led the way through the lobby, through a secret door that was padded and green. The door closed quietly. They went through a corridor lit with a purple light. The carpet underneath their feet was plush. At the far end of the corridor, they heard the orchestration from a Monteverdi opera. Then the voices came on, singing in their haunting tones. For most of the walk, the concierge had been silent. As they neared the room at the end of the corridor, he paused and said:

“None of the usual people are here. But there are some big hitters.”

“Where from?” said Arthur.

“The Middle East, Australia, France. There’s an oil tycoon, and a chap who made a billion in Silicon Valley.”

Arthur whistled. It was a good whistle, almost professional.

“I’ve never heard you whistle before, sir.”

“Secret skills.”

“Yes, sir.”

“What’s the game today?”

“Whatever you choose.”

“Keep the champagne coming.”

“You usually have water or nettle tea.”

“With these big hitters? No, I intend to have fun.”

“Fun, sir?”

“Yes.”

“You always say it’s business.”

“Then it’s about time that business was fun.”

“Yes, sir. That sounds about right to me, sir.”

“You bet it is.”

They found themselves in a spacious room with a domed ceiling, low chandeliers, padded walls and a large octagonal table around which people sat in deep shadow. Faces could not be made out. The chandeliers gave out no light but seemed only to add to the mystery of the place. The men and the lone woman round the table lifted their heads when he came in. They took him in briefly and then lowered their heads again.

“I forgot to tell you about the woman, sir,” the concierge whispered.

“Who’s she?”

“Millionaire daughter of a famous —”

“I can hear you talking about me,” the woman said, her voice smooth, airy and intelligent.

“Only with admiration,” Arthur said, taking his seat opposite her.

“Is this the charm before the kill?” she said.

“If you need me there’s a button just beneath the table, near your left arm,” said the concierge, bowing as he left.

“We thought you weren’t coming,” a voice said from round the table, a deep, slightly irritable voice.

“You can’t get rid of me that easily,” Arthur said.

“Shall we begin?” said another voice, younger, more eager.

The game began. It was a card game. Arthur recognised the rules almost immediately from his wasted youth, in which he had indulged in every known gamble known to man or woman. But it took him some time to warm up. During that time, he was pretty astounded by the level of betting and the quality of aggression in the playing. The woman was the most aggressive of all. It was as if she had something to prove. And she seemed to be proving it. Proving that she had the right to be there. Her aggression seemed to pay off, too. She won big hands.

“You guys shouldn’t be soft on me because I’ve got boobs,” she said, “because I will take you all to the cleaners without the slightest hesitation. Give me your best game. They say you guys are the best, so don’t hold back. Give me your best shot.”

This appeared to spur on most of the men, but to little effect. She went on beating them. She made hundreds of thousands in a short time. She was glowing in it, but trying not to show it, trying not to gloat. It seemed so easy to her. But she didn’t notice that Arthur wasn’t betting much. He was silent. He wasn’t saying much, either. Something about the way he sat made them not really notice him. He was right there with them but was also a little invisible as well. He didn’t have to do much to be invisible. He made himself a little smaller, that’s all. And made sure his thoughts weren’t loud. He’d learnt early on that people broadcast themselves too much. Too much chatter coming out of them. You can feel it just by looking at people. He kept calm and still, and whenever any of them round the table addressed him he gave a meaningless grunt or said something inconclusive.

“Sure is hot.”

“What was that?”

“With weather like this...”

“Did he say something?”

“Huh!”

Then their minds would drift off him and focus on where the money was going, which was usually to the woman. It seemed she had the place sewn up. There was a look of power and confidence about her now. Arthur noticed that she was less beautiful the more she won. He wondered about that. How could that be? It should be the other way round. Then he realised, in a flash, that winning was new to her. That she had only just figured it out and it was altering her whole psychology, taking her away from herself, into a new place where she didn’t know how to be or how to control her new certainties. It was at this point that Arthur decided to enter the game. He began by allowing himself to lose first. He deliberately lost some big hands. He gave the impression of incompetence, which confirmed, he guessed, the secret impression they had of him anyway, without him having to do anything. In this way, they paid less attention to him. And by now he pretty much knew how they all played. He knew their stratagems, knew what they thought about one another, and, more crucially, he knew what they thought about themselves. And they were all wrong, Arthur realised, in their self-estimation. It was where losing began. With wrong self-estimation.

Watch Ben Okri read an excerpt from A Fable About Colour

Arthur never let himself estimate himself wrong. That way lay disaster. In any case, the world had already done an estimation of him. It was a low estimation. In some cases there was no estimation at all. He didn’t believe the world’s estimation. He never did. What did the world know anyway? It didn’t know him. It didn’t know what he was like inside. Didn’t know his thoughts or how far or strangely they could stretch. Didn’t know the twists and turns of him or the curious ideas he had or how long he could go without love or water or what he could withstand or what he could endure, what he had endured, what he had gone beyond. The world’s estimation was all wrong and that was a good thing for Arthur. The world thought something was good just because it looked good, or that someone was clever just because they sounded clever, or that someone was stupid just because they behaved stupidly. The world could never see below the surface of things and people. This was a really good thing for Arthur. It made the world a good game to play. It made the world one big game. So long as you never took it seriously it was the best game ever to play. It had taken him a long time to see that it was such a good game. He had taken it seriously when he was younger. He had taken it tragically. It became a tragedy because he had taken it tragically. Then he got fed up of it being a tragedy. He got fed up of feeling bad about being alive and having no estimation in the eyes of the world. And then one day he got it. He saw that it didn’t have to be tragic. It could just as well be a comedy. That was something new. A comedy was something you had a good laugh at. It was something you didn’t take seriously. That was such a better way to be. Life changed when he saw it that way. The trick, he came to learn, was never to laugh at it so that people saw you laughing. The comedy had to be kept inside. It had to be kept hidden. The laughter had to be silent. Had to show in your eyes only. And not even there.

Sitting at the table with the players, he had watched them lose interest in him because he was losing. One of them even thought he could make a joke about it. He made a joke about it and the others laughed. They all laughed except the woman. Maybe she didn’t laugh because she felt the tide turning. She wasn’t winning quite so much anymore. In fact, she had lost two big hands. Arthur let himself win a gentle hand. Then he won a bigger one and lost two small ones after that. He was waiting. He didn’t want to rush in. People must feel comfortable. They must feel confident. Nothing big happens unless people feel confident in themselves. They won’t put big money out unless they have big confidence in themselves. They have to get a bit tired, too. And their estimation of you has to be pretty poor. Then there is the timing. That’s everything. Arthur felt it mounting. He felt the moment coming round. Suddenly the pot was huge. Everyone had gotten suckered in because everyone was feeling confident. The pot grew and grew and everyone felt sure they had the best hands and they doubled and raised and before everyone knew it they found themselves staring at the biggest pot of the night. It came to over a million. Most of them had sunk all their money in it. This was the moment. Arthur knew that this was the moment. And he had managed to get here, to stay in the game, without being seen. The pot was so huge it practically obscured the people on the other side of the table. People had thrown on their unbelievably expensive watches, keys to their Lamborghinis. One even threw in the title to a small flat in Mayfair. This was the moment all right. The silence round the table was almost lunar.

Arthur craned his neck to get a good look at his fellow players. One was tapping away at the edge of the table. Another was pulling at his nose as if it were a magic lamp. A third was glazed in the eyes and muttering something under his breath. A fourth looked as grim as death and as mean. A fifth sat bolt upright, his hat at an angle. The sixth, the woman, looked almost skeletal. Her face was drawn tight and her skin seemed sallow in the murky light the beige table bounced back to her face. She had been beautiful when the game was young. Now her beauty had drained into the stack of money and tokens that formed a mound on the table. Her eyes were pale and he couldn’t tell if she were on the verge of tears or was concealing a rude smile.

At that moment the concierge came over to him.

“Would you like a drink, sir?”

Arthur glanced up at him. The concierge looked strange. The size of the pot made him look strange. The light from the table was altering the tone of everyone’s skin. The light of all that money seemed to make them look like cadavers.

“This is the highest round ever seen here, sir,” he whispered.

“Who ever walks away with this could retire for the rest of...”

“I’ll have a nice fresh glass of champagne, please,” Arthur said aloud.

“Mr Loser here needs a drink,” said one of the men across the table.

“Can’t take the heat?”

Arthur said nothing. He had learnt never to announce his victory in advance. He was too superstitious to play with fate in that way.

He never gloated, never preened, never boasted, never crowed. He never looked as if he had won. Even when he had won he never let himself look as if he had won. Too many people did that. He had learnt over the years that this was where the real losing happened. When you had won. He wasn’t afraid of winning. He knew how to win. That was why he was still around. He was a big winner all right, but the trick was never to show it. Then it can be taken from you. They take it from you. Sometimes even you take it from yourself. Besides, what was the point in showing it? What did it do? He always thought that the true strategy in life was: If you have it, don’t flaunt it. This was much the wiser mode than the other, more commonplace saying. That’s what people did anyway. They were always flaunting what they didn’t have. If you flaunted anything, it couldn’t really be yours anyway. One can’t flaunt what one truly owns. What can one own anyway, either, come to think of it? Arthur always thought that tranquillity was the real sign of having, or of having been bestowed with, something. The universe, for a time, merely made you a gift. It wasn’t yours. And so he never thought of winning as winning. He thought of it as sitting in a state of grace, sitting still inside a great gift he’d been given. That way, he was never dominated by winning. He never liked the look of people who flaunted their winning. He noticed that they pretty much always came to trouble afterwards anyway.

And so Arthur said nothing. The joke on him was passed around the table and one or two people snickered. The woman looked up at him over the high pile of the bets and her eyes were cool and measuring. Perhaps she saw him for the first time.

“I like that guy,” she said. “He’s been here all this time like he’s not been here. That takes character.”

“Loser character,” snorted the man who’d begun the joke.

At that moment the concierge came in with a long-stemmed glass of champagne. The glass was beaded with dew on the outside.

“Here’s your drink, sir.”

“And I might need some heavies to protect what I’m about to do next,” Arthur whispered to the concierge. “And a big bag to carry it with.”

The concierge looked at the table and back at Arthur and bowed swiftly while departing. Arthur took a long sip of the champagne and felt instantly calmer. He knew that feeling well. It was the feeling he had when he had moved from anticipation into reality, when he had entered, in advance, a state he had dreamt about or wanted, when it became real in his body before it became real to everyone else.

The moment had come to reveal their cards. The man who made the joke, a man in a cowboy hat, was the first to put down his cards. He laid them out as if they were a foregone conclusion. His face was slightly sweaty, his hands quivering lightly. The man next to him then showed his cards with a short, explosive sound from his mouth that did not have any correlation with language. Then the man on the far side of the table unveiled his. Each unveiling was marginally better than the other.

Then it was the woman’s turn. As she revealed her cards, the concierge glided smoothly into the room with four other shadows that slid along the wall and remained there inconspicuously. The woman looked up momentarily and, laying out her cards, said:

“I said to give me your best shot, boys, and you did.” She paused.

“And it just wasn’t good enough, right?”

She sat back and waited. The silence in the room thickened around Arthur. At first, everyone’s eyes were on the woman. The men had mostly turned pale. The man with the cowboy hat had taken it off, pulled out a handkerchief he kept inside it, and mopped his sweating face. No one considered Arthur. He had been forgotten. The darkness in the room had cast him into oblivion. As the game had progressed, the lights had been made dimmer. Arthur had seemed to retreat into the dimness. Only his eyes remained. The woman leant forward. No one had contested the superiority of her cards. She opened out her arms and was about to begin the gesture of ownership when Arthur moved. It was a small movement, but it shifted all the vectors in the room. The players became alert in minute ways. A head turned towards him at an angle. Someone made an indecipherable sound.

The woman, who had been leaning forward, said:

“Oh, but, surely...”

Then, like a magician pulling something big out of something small, pulling a large telephone directory out of an average-size handkerchief, Arthur proceeded to lay out his cards on the table, each card, in its unveiling, seeming to be larger than the preceding one. He had barely laid out the whole sequence, for he was doing it slowly, when the man with the hat burst out:

“He can’t possibly! That would be too much”

At that moment, Arthur signalled to the concierge. He and the men he had brought, who up till then had been shadows attached to the wall, drew closer and discreetly surrounded the table. Arthur laid out the rest of his cards and one of the men across from him said:

“It’s like being subjected to a slow execution.”

Then Arthur sat back and let the quality and the nature of the cards sink in. The woman stared at it in bafflement and then looked at the other men for confirmation. Disbelief hung palpably in the air. Up to this moment, Arthur had said nothing. All he did was finish off the rest of the champagne in his glass, as though it were a painful, but necessary, duty. Then he wore a mournful expression. Anyone seeing him would think that he had just been dealt the worst defeat, rather than the other way round. It was, in effect, a complete rout. He had cleaned everyone round the table of everything they had. He struggled for something to say. His hands struggled and his face struggled. At last he came out with something.

“I don’t suppose...” he began.

Then the man with the hat rose abruptly.

“That’s me done,” he said, and he gave Arthur a long look. “I’m not sure what you just done here, cowboy.”

Walking past the bouncers, who had become shadows round the table, he left the room. None of the others moved for a moment. Arthur made no attempt to claim the money on the table. He sat watching the others, his face in shadow, only the whites of his eyes showing. Two of the men round the table whispered to one another and got up. As they rose, Arthur signalled to the concierge. Swiftly, with the efficiency of a veteran bank robber, the concierge appeared at his side with the bouncers, who began to pile all the bets on the table into a smart looking white suitcase. The whole operation lasted less than two minutes. Then the suitcase was snapped shut and left by Arthur’s side. The bouncers returned to being shadows on the wall. The concierge stood by Arthur, who still hadn’t moved. The two men who’d stood up had their moment of exit broken by the efficient operation, which they watched the way restaurant clientele might watch a chef preparing a gourmet dinner before their eyes.

The moment the suitcase was snapped shut, the two men left. A moment later two others followed. The last player left was the woman. Arthur got up from his seat and went over to her and stood behind her chair.

“May I?” he said.

She rose and looked into his face from close up.

“How did you do that?” she asked.

“Do what?”

“That?” she said, pointing at the table.

Arthur looked back into her face. She was beautiful again, and rich and fragrant. They had been sitting in their seats playing for hours and yet she still gave the impression of having just come fresh from a bath. A light aroma of expensive perfume wafted from her person.

“I didn’t really do anything,” Arthur said. “It was all pure luck. I just let it happen. The trick is to let it happen.”

“What are you doing afterwards?” she asked suddenly, something changing in her face.

“I hadn’t thought that far.”

“I don’t believe you,” she said. “People like you think seven steps in advance.”

“That’s too laborious,” Arthur said. “One’s liable to get one’s feet all tangled up.”

“Dinner?”

“Dinner would be delightful,” Arthur said.

“At eight, main restaurant?”

“See you there.”

The woman picked up her little golden bag, turned abruptly and left. The concierge opened the door for her. As soon as the door shut behind her, Arthur, suitcase in hand, said:

“Is there another way out of here?”

“I thought you’d want to know that. Follow me, sir.”

The concierge led him to the far wall. The wall turned into a door and opened outward. Two turns in the corridor brought them to another secret lift.

“For customers who need to make a quick getaway. Also sometimes used by the royal family.”

“Do they play?” asked Arthur.

“Not when they play, but when they have exclusive dinners.”

The lift door opened. Arthur stepped in.

“Will you be needing anything else, sir?”

“In an hour’s time, perhaps,” said Arthur.

“I will see to it, sir.”

In the room, Arthur checked his winnings. Then he switched the winnings from the white suitcase to one of the darker bags brought in earlier. He had a quick shower and changed back into his original clothes. He cast one more look round the room and looked once more out the window into the park where the leaves were falling from the horse-chestnut trees in the early evening. It would be nice to stay and savour it all. It would be nice to stay longer till you are found out and everything is lost. There’s just a moment. But a moment longer than that, and it’s all finished. But wouldn’t it be nice to stay a moment longer, he thought.

He left a note on the table for the lady he was to meet at dinner, along with a substantial tip for the concierge, substantial enough for him to retire and live in comfort. He also left in a bag the £50,000 that had been sent up to him. Then he went to the door, took the lift down, and instead of heading outward, to the lobby, he made for the corridor that led to the secret door that gave onto the street.

He put on a cap he’d taken from his inner pocket, and flipped it on backwards. Then, assuming a slouch, he made his way through several back streets till he found himself in the park. He sat on a bench and breathed in gently the cool evening air. He looked back towards the hotel. He could see his room. Someone was at the window looking out. He enjoyed being in the park that he had been looking at. He sat there long enough to re-adjust. He wouldn’t be sleeping rough anymore. He would check into another hotel, have a pleasant night’s sleep, and in the morning he would set about buying himself a flat. He had money to last him the rest of his life if he lived sensibly. He would never work again. He would never put himself in a situation where people could affect his life because of their prejudice. He would live free from society and from people. He would not live a life anymore in which people could determine the quality of his experience. He would live above society. He would be free. Every day he would set out into the world and see what the world wanted to make of him, what it wanted to project on him. He would live life as a game.

He thought about the woman who would be waiting for him at eight o’clock. She was nice. Such a shame not to discover what she was made of, not to get to know her. But that could be his undoing. He had to be clear-headed. The thing is not to be caught. The thing is never to be caught.

That’s how it was. That’s how it was that morning. The world will do what it does, and he will do what he does. He was going to give the day the chance to define itself around him. He didn’t have to work. All he had to do was play. All he had to do was study people, study the world. Today he was going to stand somewhere different. He hadn’t chosen where yet. But he would. He would just stand there, his mind empty, and he would wait to see what the world had for him on this day. He walked till he came to the opera house. That was it. He recognised it immediately. This is where he would be for the day. And so he stood there, outside the opera house, watching men in bowler hats with rolled umbrellas go in through the big glass doors and come back out again. He saw women in ball gowns and little handbags under their arms go in and then come back out again. They didn’t look different when they came back out.

As he stood watching, a fine-looking car drew up near him. The driver came out and bounded into the opera house building. While he was there another man in a bowler hat came up to him and said:

“You must be my driver. Well look sharp about it. Let’s be off then.”

“Of course, sir,” Black said obligingly, slipping into the driver’s seat.

“Where am I taking you?”

–

Sir Ben Okri is a Nigerian-born award-winning poet, playwright, novelist and activist. His books include the Booker Prize–winning The Famished Road and Astonishing the Gods, which was selected as one of the BBC’s “100 novels that shaped our world.” His work has been translated into more than twenty-eight languages.